Population Politics

Breaking down responses to address FUHSD’s declining enrollment issue

The story of Sunnyvale High

Sunnyvale High School was closed following a unanimous vote from the FUHSD board in 1981. At a March 3, 1981 board meeting, district program manager Jerry Figgins cited factors such as “the district’s standard of excellence in educational programs” as well as concerns of providing “significant educational value for students through reduced costs” as two key reasons for the closure of SHS.

According to an earlier set of board meeting minutes from February 3, 1981, the root cause of these issues stemmed from various economic factors. A combination of fixed property taxes as a result of Proposition 13 combined with a high interest rate of 13% not only had lowered overall school funding, but also had lowered the rates of real estate sale, as the interest rate prevented people from taking home loans. Because public schools accrue a majority of their funding from property tax payments, the district had taken a major hit and would need to use state support for their budget. According to a June 16, 1981 board meeting, when comparing the pre-proposition income distribution for the 1977-1978 budget, 73% came from local sources (like property tax) and 21% came from state support. Following the enactment of Proposition 13 however, the funding changed to 32% and 62% respectively for the 1981-1982 budget. FUHSD superintendent Graham Clark states the district ultimately decided to close SHS to resolve these financial issues, and while there were plans to close another school, the end of the inflation period led to a change in plans.

“The first idea was more minor cuts like busing [and] summer school, then they followed up [and realized,] ‘Okay, now we got to close a school — it’s just too expensive,” Clark said. “They were looking at closing a second school, and it likely would have been a school in Cupertino, but they stopped it in the 1980s [because] the employment and the economy turned around in Santa Clara County.”

The SHS campus now officially serves as the campus of The King’s Academy, with 700 students living in the former SHS attendance area north of the campus. Now, almost 50 years later, declining enrollment has once again become a major issue amid rising house prices and home availability. By creating a Citizens Advisory Committee (CAC), the district has sought to implement possible solutions to both current problems in FUHSD and new issues that may arise with continued declining enrollment. Here are six of the various proposals introduced by both Clark and the CAC to address this problem.

1. Doing nothing

If the problem is not addressed, Clark says schools with a lower enrollment will continue to strip departments, increasing the chances of shutting down the school. However, while Clark doesn’t see this as a possibility within the next five years, he aims to continue to solve problems concerning disproportionate enrollment.

“If [the district population] gets smaller [than current projections], it can be problematic,” Clark said. “But for the next five years, we will have problems when one school has 1000 [students] and another school has 2000, because opportunities between those two schools [will be] quite different.”

2. The Band-Aid

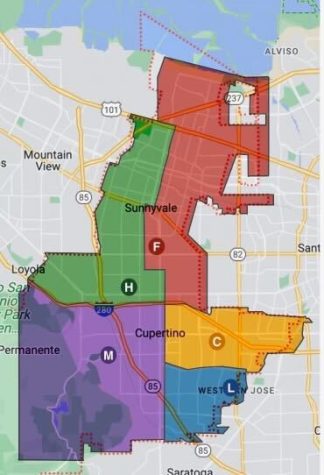

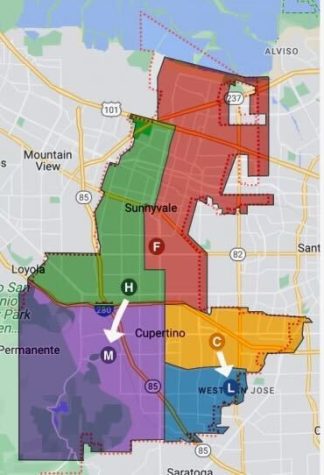

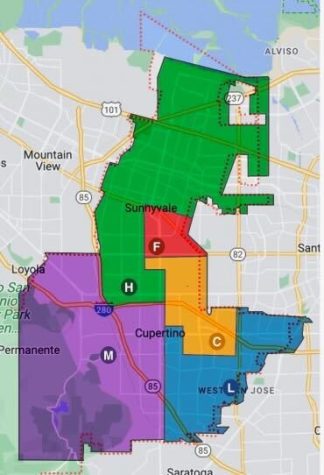

Currently, Clark states the primary action FUHSD has taken to deal with declining enrollment is an initiative to transfer students from certain school zones at schools not facing as severe a decline, such as FHS, HHS and CHS, to schools that are declining more rapidly, like MVHS and LHS.

The FUHSD Board, alongside the CAC, has approved two school transfer programs: the Lynbrook Supplemental School Assignment Program and Monta Vista Supplemental School Assignment Program. The LSSAP has effectively slowed the population decline of LHS by maintaining a steady increase of 75 students from CHS, which helped lessen the decline of student population at LHS by 300 over four years. However, Clark says the program’s passing was difficult and was met with much opposition from the LHS community.

“We did have a lot of pushback, the original idea was that the people in [in the CHS attendance area] would be allowed to choose to go to Lynbrook High School, but it was alluded to [that] if [the] area choice works out we’re going to do a boundary change,” Clark said. “People got really angry about that, [and] although it sounds simple, the Citizens Advisory Committee studied it for six or seven meetings before [coming up] with a recommendation.”

In the past year, a similar process with debates and compensations has led to an agreement in the MSSAP with a transfer of 30 students from the HHS attendance area to the MVHS attendance area each year, with this exchange starting in the 2023-2024 school year. Clark says the application process has been finalized, but its results were underwhelming — only 23 students in the HHS attendance area chose to go to MVHS instead. Furthermore, eight of the students who are part of the transfer did not plan to go to HHS and were instead planning to attend a private school, making the resulting transfer from HHS to MVHS only 15 students, which was half of the goal.

Having taught at both MVHS and HHS, Economics teacher Pete Pelkey believes that this was a predictable outcome, noting that low amounts of incentives serve as key reasons to the low turnout.

“I can’t imagine why 30 kids would want to come here,” Pelkey said. “If all your friends are at Homestead, why would you want to come to this school where you don’t really [have that]? I don’t know why you would do that, [and] I don’t know why [MVHS] would be a more desirable place.”

While Clark says FUHSD does not want schools to decline at vastly different rates, Pelkey disagrees that the five FUHSD schools must be similar. He believes the school transfer program is unnecessary, and having different populations is acceptable, even if opportunities for students may differ.

“I would not worry as much about class offerings,” Pelkey said. “I think the fact that we’re homogenizing the district by ‘McDonaldizing’ it — [making] every school have to look the same when there’s obviously a difference — I’ve never been for that. Tailor school to what the kids need — that’s what we should be doing. Servicing their community should be the attitude, not ‘everybody’s exactly the same comrade, everything is perfect.’”

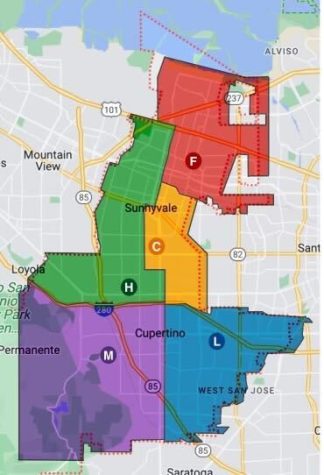

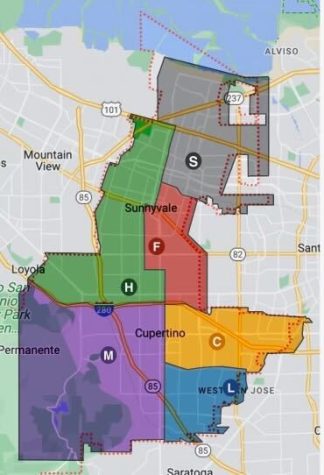

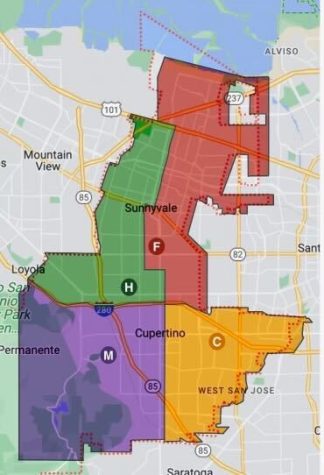

3. Drawing new lines

The current school zones have been relatively stable since the closing of Sunnyvale housing in 1981, according to Clark, as school zones are established with housing developments, and development has slowed down in recent decades. Recently, new developments have brought rezoning to the table, but Clark says moving proposed zonal maps into action is complicated.

“[Rezoning] is possible, [but] it’s not easy because you have to get the people that live in that area to agree to it, and then you have to get the county to agree to it,” Clark said. “Getting consensus from all those people is sometimes hard. Some people, I’m going to say, get very emotional about this idea [and] you have to deal with all those feelings.”

Pelkey has worked around FUHSD and thinks rezoning would be complicated as parents at schools in more affluent areas like LHS and MVHS do not want the zones to change because of the demographics of less prosperous neighborhoods. He also believes zoning would be hard to execute from a logistical perspective because of how property values are related to schools.

“[The] problem with rezoning is powerful parents don’t want their property values to change,” Pelkey said. “If you’re going down Wolfe on the left and the right, the [houses] going to Fremont generally are $100,000 to $150,000 more than the ones on the other side of the road, which go to Wilcox — that’s [what] going to a better school can do to your property values.”

Although Clark does see rezoning as a potential solution, he also says that all schools at FUHSD have zones that do not extend farther than six miles, asserting that rezoning might not be necessary since the current zones allow students in FUHSD to attend a nearby school.

“Most people value neighborhood schools, and we’re stretching it a little bit [in North Sunnyvale] because these are further away, by FUHSD standards,” Clark said. “[But by the standards of] most schools in the county, it’s not that far.”

4. Migrating North

Clark acknowledges that in an ideal world, the perfect way to make commute times for students in North Sunnyvale more equal to students in schools with smaller zones such as LHS and CHS would be to move all five district schools further up north.

“If we could move schools around, say we moved Lynbrook [where CHS is], and then we could move Cupertino [north], and then we can move Fremont [into North Sunnyvale,] we could get people closer to their school,” Clark said. “These [schools] were built in a certain time — they were built when needed at the time, and also when the land was available.”

Pelkey taught at HHS from 1994 to 2005, and recalls that some HHS students who lived in North Sunnyvale had the longest commute time out of any student population at FUHSD. He says that after the closing of Sunnyvale High School, students, mostly from marginalized communities, who live near Highway 237, were forced to take one or even two buses to get to school.

“When I was there, it was [mostly] Hispanic and African American students, and they’d have to get up early, take a bus, then they have to wait for another bus and come in — teachers don’t realize how far that is and how long that takes,” Pelkey said. “Sometimes the bus comes late, and I’d see 100 kids come in, and they’d be tardy. I once got on the phone and said to the admin[istration], ‘Why don’t you make an announcement about the 100 kids coming off the bus and 56 came in late [because the bus arrived late?]’ No announcements were made, and then those kids all have tardies and absences, and then you hear, ‘Why can’t the Hispanic and Black kids get to school on time?’”

Pelkey has other memories associated with the long commute times, such as a student who got up at 4 a.m. every morning and worked at Starbucks while waiting for the earliest bus to arrive at school on time. HHS freshman Adrian Lang, who currently lives in North Sunnyvale at the intersection of Mary Avenue and Evelyn Avenue, takes about 40 minutes to commute to school.

While Lang says the buses generally leave on time, he also says they are unpredictable. Although Lang is generally satisfied with VTA service, he has friends who live even further north and hopes the VTA can expand the line to HHS so they do not need to transfer buses to get to school. Lang also admits that he envies students who live closer to HHS.

“There are a lot of people that have a much shorter commute home,” Lang said. “I’m jealous that they get to sleep in a lot.”

Contrastingly, Clark does not believe moving schools north would be a viable solution as it would meet significant pushback from non-benefiting communities.

“If you say, ‘I just want to move it from here to here,’ you have to get people to vote for that,” Clark said. “And then you have to get 66% of the people to say, ‘Let’s move from here to here and pay $500 million’ — no that is unrealistic, it has to [have] a very compelling reason. Our community is generous because they’re giving us money to modernize our schools, but they’re not giving us money just to move [schools] around to make [commute] moderately more convenient [for busing students].”

5. Reinstating Sunnyvale High

Another proposition to address enrollment equity is to reinstate the previously shut down SHS at its current lot or a property further north to accommodate students living further away from FHS or HHS. While shortening those commutes comes with significant benefits, Clark states that the unviability of this plan stretches beyond just a lack of community support, as FUHSD schools must be strategically located to address their local populations and must be large enough to accommodate an appropriate student population.

Assuming the plan to renovate SHS is chosen, Clark states the district would need funds exceeding $500 million, which would be difficult to acquire.

“We just passed a bond for $275 million, and it barely passed, so could we say, ‘Hey, [we might] close a school in one area of the district and try to open [SHS in north Sunnyvale], and everyone’s gonna pay over $500 million’ — we just don’t think that’s going to pass, that’s the reality,” Clark said.

Furthermore, Clark says a renovation project on the old SHS campus would mean adhering to safety standards set by the Americans with Disabilities Act, which Clark states are constantly changing with time. According to Clark, building ramps or lowering floor grades for wheelchair accessibility would mean rebuilding the former SHS campus from the ground up and risk exposing large amounts of chemical waste located three feet underground.

Clark believes there are no other appropriate 50-acre lots in north Sunnyvale due to toxicity resulting from the city’s industrial history, the ban on building near the Moffett Federal Airfield and commercial developments. As a result of all these factors, establishing a new school in Sunnyvale would prove to be a nearly impossible task.

“I don’t know what will happen [in the coming years],” Clark said “I think long term when [the district is] declining in enrollment, I’m trying to keep all five schools open, but the idea that we would open a six isn’t [practical] —[we] can’t afford [it.]”

6. Shutting down a school

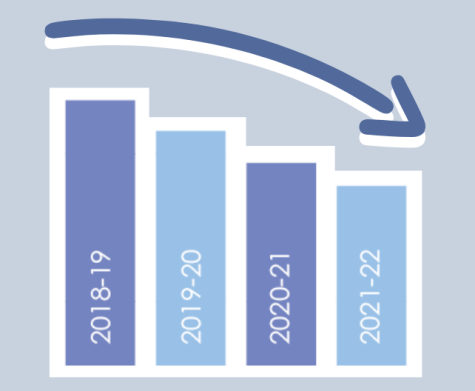

According to Clark, a school shutting down can be a conceivable future if the district’s enrollment continues to disproportionately decline across its five schools. Clark states the major factors contributing to the decline are linked to limited new homebuyers with children and a lack of high density housing provided in the local areas surrounding these two schools.

Historically, the board and local community have suggested various metrics to determine what school is shut down. Board meeting minutes from February 3, 1981 show community members discuss factors such as academic performance, personal safety, lengthy commutes and overall community benefit. Alongside this, members of the Board also discussed concerns over the importance of a school in helping disadvantaged communities, such as aiming to preserve schools that receive both Title I and Title VII funding. In the discussion determining which school shuts down, Clark cites that community involvement will play a major role in defining how future decisions are made.

“We have people that want to be close to their school because they’re very involved in activities,” Clark said. “I think that’s the strength of [FUHSD], and over time, the diversity of our schools has matched the diversity of our community.”

While Clark says closing down a school is not optimal and would be met with a largely negative response, it may also be the only course of action the district will be able to take in the coming future.

“Based on what we’re seeing, every [school] is going down [in population], but we want to go down equally,” Clark said. “If the schools are not an equal size, you’re gonna have more opportunities for classes at the larger school at some point, and when you get really small, we just can’t offer [certain] classes anymore — we don’t have enough space.”

In conclusion

As it stands, Clark says the district aims to solve declining enrollment by redistributing its dwindling population equally amongst all schools to maintain equity academically. There are various ways to achieve these goals, but many hold mixed or impossible results. On the other hand, Clark explains that local community members hold a variety of concerns with taking action on redistribution measures, some of which include asset values, long transit times and concerns over changing academic environments. Ultimately, Clark believes in the district’s ability to address the issue while making sure to place equity at the forefront of their approach.

“[FUHSD is] committed to make [solutions] as fair as we can in our situation,” Clark said. “Every year we look at enrollment projections, and they’re pretty accurate, so it’s not a surprise to us when our freshmen class is a certain number, but what we don’t know is what’s going to happen five years out. There are a lot of things changing in our economy. Perhaps something will happen that will bring more kids in here. We’re trying to manage it as best we can — we’ve had some success with what we’re trying to do.”