Cupertino addresses homelessness through a city plan and partner programs

Exploring what organizations are doing to alleviate the homelessness crisis

March 23, 2022

The city of Cupertino intends on adopting an official city plan to end homelessness by this summer, becoming the first city in Santa Clara County to develop and begin the drafting process. Added to this year’s City Work Program, the plan will address homelessness concerns and needs, informing decisions on funding and program implementation.

Following a four-step process, the city launched the initiative in the fall of 2021 and is currently gathering community input. On Feb. 10, Cupertino hosted its community kick off meeting, giving a basic overview of the plan and informing residents on next steps. During the meeting, participants could also ask questions and pitch suggestions to the city.

Gabriel Borden, a senior housing planner for Cupertino, says that the main input gathering is done by their partner organization HomeBase. HomeBase conducts interviews within focus groups that span a diverse range of experiences from people who have been homeless before to community stakeholders, eventually consolidating the interviews to form a draft of the plan. During a 30-day public comment period, the draft will be published on the city website where anyone can comment on the plan’s content. The feedback will be taken into account when producing the final draft, which will go to the housing commission and the City Council.

The city plan complements the Santa Clara County Community Plan to End Homelessness, which was released in 2020, and will follow a similar framework, tailoring the approaches and goals to account for the specifics of Cupertino. This means considering what resources are available and how the city can fill in potential gaps in the county plan.

“Our City Council looked at [the county plan] and was like, ‘This sounds great, we’re going to adopt it,’” Borden said. “But it doesn’t really say specifically how to end homelessness in Cupertino, so we felt we needed a plan specifically for our city. The unique demographic [and] funding sources [all] need to be considered. If the county says [they] want to reduce the inflow of homelessness by 30%, the city plan might say something similar but it’ll say how Cupertino can specifically do that.”

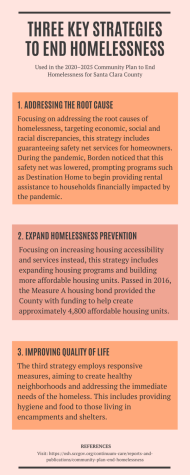

Although the plan has not been drafted yet, Borden believes it will follow the basic framework of the county’s plan, adopting the three-tiered approach at counteracting homelessness: “Addressing the root causes of homelessness, expanding homelessness prevention and improving quality of life for unsheltered individuals.”

Previous Progress:

The City has been biannually collecting data on the homeless population residing in Cupertino through what is called a “point-in-time count.” The most recent data is from 2019, since the pandemic interrupted the 2020 and 2021 count. The 2022 count started in February and the data is projected to be released this summer.

In 2019, Cupertino had recorded 159 homeless individuals while Santa Clara County had 9,706, both at an all-time high within the last decade. Borden anticipates the upward trend will continue into this year since many of the root causes of homelessness — such as a lack of affordable housing and living wage jobs — are still present, with the COVID pandemic exacerbating these issues.

“It’s a massive issue,” Borden said. “Unfortunately, it’s not going to get solved in a matter of a year. I would love it if that were the case, but it’s going to take, as the community sees, significant resources to solve this, not only at the Cupertino level, but also the county level and the Bay Area level. And eventually at the national level, because even if one town says that they don’t have a homeless issue, that doesn’t mean that doesn’t exist — the root cause hasn’t alleviated elsewhere.”

Senior Dominic Wang agrees with Borden that homelessness is a serious issue in Cupertino, even if it is known as a more affluent city. They think the stigma around homeless people prevents them from economically mobilizing and “dehumanizes” them and their struggles when in reality “they are just trying to get by and survive.”

Debbie, who is 62 years old and currently homeless, emphasizes how this stigma stems from the general unawareness of what it’s like to be homeless; she describes how she still has to pay bills to fix her car and send money back to her grandchildren, stagnating her ability to maintain stable residency. Although she hasn’t received any official support from the city, she thinks her experience in Cupertino has been generally welcoming due to the community support she’s received.

Partner Programs:

The City currently collaborates with different programs and organizations to provide services for those who are financially struggling. A key partner that the city works with is the non-profit organization West Valley Community Services that helps alleviate poverty by providing support to low-income individuals, receiving funding mostly from government contracts and in-kind donations. According to its impact report, its services helped 3,168 individuals across six different cities and 22% of its clients were from Cupertino in 2020.

WVCS provides individualized services to each client through one-on-one meetings with case managers, which Executive Director of WVCS Josh Selo describes as the “navigator system” for the client. When a client comes in for the first time, the case manager uses a tool called the self-sufficiency matrix to measure different domains such as housing and employment to design a plan to address their needs. The case manager will recommend different assistance programs based on the plan and if WVCS doesn’t personally provide the program, the case manager connects the client with external agencies that do address that area.

“It might be that [the client] only needs one thing, which is food, and once they get food, they’re good,” Selo said. “We have a number of clients that only use this for food because that’s the thing that helps them maintain their self sufficiency — they just don’t have enough money to stretch their budget after rent to pay for food. However, if you’re talking about someone who is experiencing domestic violence, they actually need more support than we provide them with. They might need food, they might need rental assistance to move into their own place, they might need counseling, they might need childcare, they might need a host of other support which we don’t provide. That way then the case manager helps connect that individual client with other resources that the client needs to move towards that self-sufficiency situation that addresses their crisis.”

WVCS focuses on two core services: food and rental assistance. Food is free and available at its stationary Food Pantry Market and Park-it Market, which is a mobile food-truck that travels around the community on Tuesdays and Thursdays. The Food Pantry Market is located at the Cupertino headquarters and functions similarly to a grocery store where clients can walk-through and pull items off the shelf. Toni Concepcion, the manager of pantry operations, acts as a liaison between the donor stores, making sure that there’s enough food to feed its clientele on a weekly basis.

WVCS receives its food from farmers markets, Second Harvest Food Bank and other donor stores such as Costco, Target, Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods. Their current market is stocked with a variety of products that cover each food group and account for different dietary restrictions. It also includes a “Heart to Home” section where those facing homelessness can access backpacks, sleeping bags and hygienic products. The market serves a wide range of people and Concepcion has seen its impacts spread across the community.

“The biggest impact that I see [these services have] is with the seniors,” Concepcion said. “There have been mostly seniors that have been on fixed incomes for the longest time and they actually do depend on West Valley. There are groups of seniors that actually do plan the day that they come, and they come in here on, let’s say Monday, and we are basically one of their main outings for the week. Some of them do become regulars here [and] we do find out what their favorites are and we try and get them for them.”

Beyond food, WVHS currently provides $1.2 million in rental assistance for those either currently homeless but more commonly, those at risk of homelessness, since it’s more expensive to house someone than to help pay their rent for a few months. WVHS also currently owns 28 units of housing that they rent out as part of the city’s below market rate housing program.

Selo thinks the price and lack of affordable housing is the most significant factor impacting clients — if they had stable and affordable housing, that would “solve a big problem.” Debbie agrees with Selo and details how the current housing system isn’t efficient and prevents her from finding permanent housing.

“It’s been really rough,” Debbie said. “I don’t make enough money to live sometimes. Over the years, my credit has gone bad, so it’s hard to get in any place, even if I could afford it. And I’ve just been on the streets and trying to get [housing]. I’ve tried homeless shelters, and now you can’t even get into one. And even to get into housing, like low housing, which is like paying $300 a month for your rent, there’s a 10-15 year waiting list — I’ve been on there for a very long time.”

The minimum wage is also too low to meet the housing cost in Santa Clara County — in order to be self-sufficient in Silicon Valley, which Selo describes as being able to buy food and pay rent, one has to earn $27 an hour while the minimum wage is currently $15.

“The math, it doesn’t bear out,” Selo said. “People are set up to not be able to succeed in these professions that we need people to work in. We need people in the service sector. We need people in stores. We need people in coffee shops. But we’re just not compensating them at levels that meet the cost of living here.”

Being at the “nexus of an incredible community,” Selo thinks that it’s “powerful” seeing both sides of the process — the clients who are “working very hard” to overcome their situation and the case managers who “invest in making a difference” by providing their clients access to as many resources as possible. Despite this working process, Selo mentions that he “would love for us to be able to put ourselves out of business.”

“I would love to live in a world where our services are not necessary,” Selo said. “That’s a question that I think a lot about. What would that mean, what would that look like to not to not be needed anymore? It sounds a little bit utopian, I think, but if there’s anything that keeps you up at night, it’s how do we get to that place where everyone has what they need to thrive?”

Borden thinks addressing homelessness needs to be done on both a macro and micro levels and encourages residents to become civically engaged with the issue. This includes volunteering for services such as WVHS or “fighting for policies that you think are going to help your community.” He also believes educating yourself and others is crucial in understanding the situation and how realizing that there are different versions of homelessness can “change the conversation.”

“In general, try to ensure that you’re not treating homeless folks as others or as someone that you think of with all these stereotypes,” Borden said. “Homeless folks are human beings; they are just like you and me, [so] have that empathy when you see someone who’s on the street. I have kits in my car and they have things that generally folks who are unsheltered appreciate: water, food, deodorant, toothbrush, toothpaste, a pamphlet that says where to go, that sort of thing. Sometimes it’s [also] acknowledging people — while you’re walking, on the side of the road, you may smile at them or maybe you say, ‘How’s your day?’ instead of having this stereotype associated [with] them.”