White passing

Forcing mixed race people to choose one reinforces arbitrary racial categories

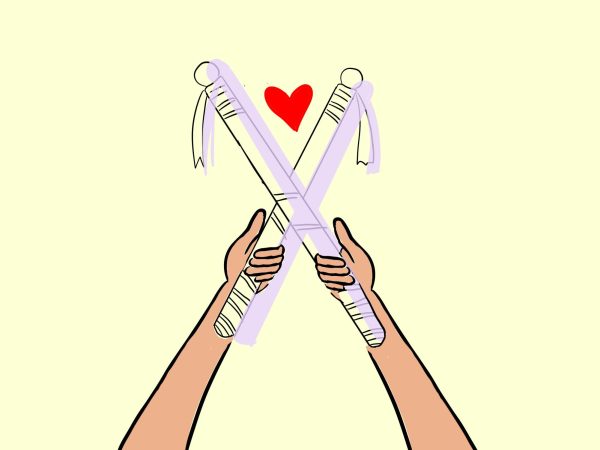

Graphic | Kalyani Puthenpurayil

People often assume other’s racial identity based on preconceived notions surrounding their physical appearance.

In seventh grade, I had a conversation with one of my white classmates about where we would like to live in the future. On the topic of racial diversity as a factor, the classmate glanced around at our Asian peers, leaned closer to me and said quietly, “I could never live here when I grow up. There’s way too many Asian people. I would go crazy. You’re probably going to leave too, right?”

I was confused by the implication. “You know I’m half Chinese, right?”

Their eyes widened in shock, and then embarrassment passed over their face. “Oh. You’re Asian? There’s no way. You look really white, I never would’ve guessed in a million years.”

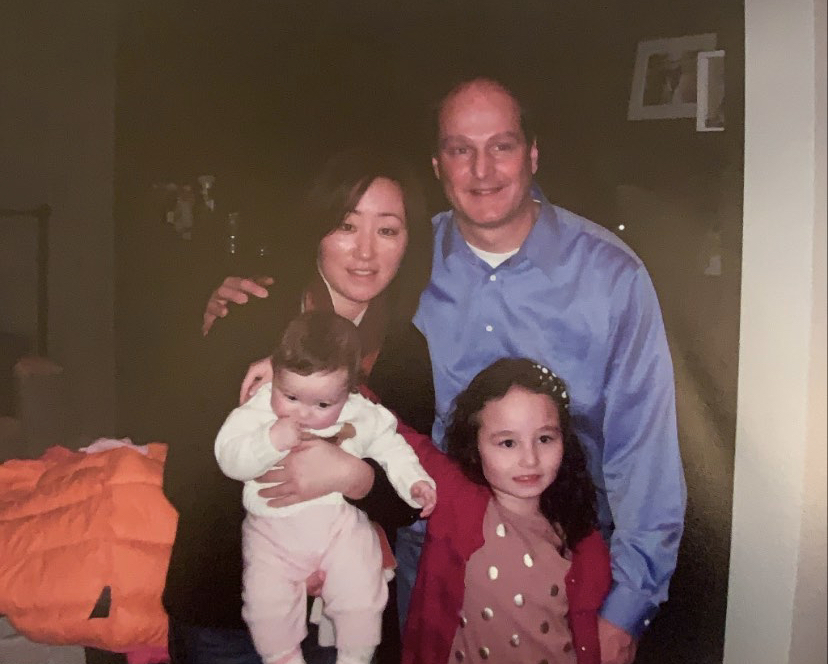

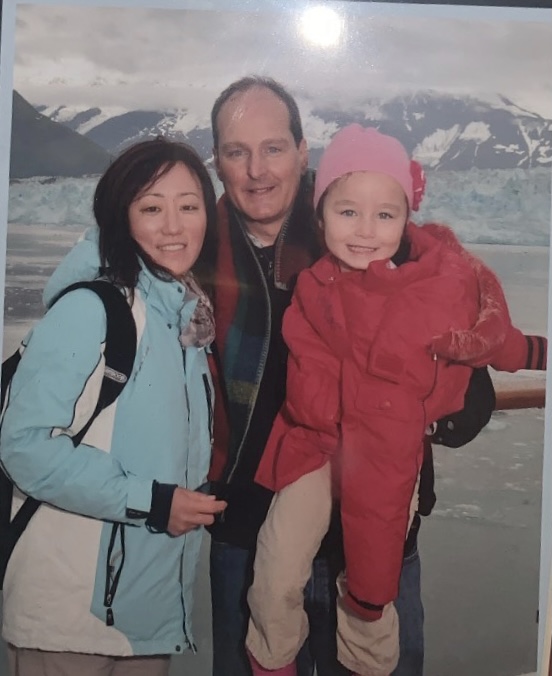

When I tell people I’m mixed race, it’s often met with exclamations of disbelief and even denial. And it kind of makes sense. I have blue eyes and brown hair and at a glance, my appearance doesn’t necessarily indicate that I am anything but white, even though I am both white and Asian. The last name “Jerolimov” doesn’t exactly suggest any Asian heritage. I could probably go around gaslighting people and telling them that I’m only white, and nobody would really question it.

When I apply for colleges this fall, I could technically select “white” instead of “other.” Would that increase my chances of getting in? White women statistically benefit more from affirmative action than people of color. I will likely never face discrimination in a public setting due to my appearance. The list of privileges goes on and on.

But even though my physical appearance is white, being Asian is an equally integral part of my identity. I often find that I can connect to my Asian peers, specifically those who are Chinese, more than my white peers because of the background we share.

And there are many things that make me different from people who are ancestrally white. Because my mother raised me speaking to me in Mandarin, (although I always respond in English), I have Mandarin proficiency that is almost impossible for non-native speakers to attain if they have not been exposed to the language from an early age. Although my first and last name indicate whiteness, my middle name, “彦迪,” shows otherwise.

At the beginning of this year in my English class, we watched a video explaining the difference between race, ethnicity and nationality, represented through jelly beans. “A person with multiple races will still ultimately belong to a racial category themselves, whether or not it’s the same as their parents,” the woman in the video explained as she divided jelly beans into different piles based on color. She explained that a cinnamon jelly bean and a cherry jelly bean, while hailing from different places, still belong to the same category: red. Essentially, she was saying that based on their appearance, everyone belongs to one specific racial category.

But people are more complex than jelly beans. Who gets to decide what race someone is? What about people who are very clearly mixed race? What about people who are generally assumed to be of a certain race, but have ethnic features that provoke questions about their ethnicity, such as “What are you?” What about people who look like one race to some people and one race to others? If the public cannot agree on whether a dress in ambiguous lighting is black and blue or white and gold, how can we expect public opinion to determine someone’s race?

And if we do use public opinion to determine someone’s race, whose voice holds more sway? Why should I listen to my white English teacher, whose video essentially dictates that I should choose a single racial category, instead of to my Asian American friends who say that I should refer to myself as mixed? My Chinese mother does not understand why I would ever refer to myself as white when that does not hold true for half of my ancestry. Shouldn’t her opinion hold more weight?

Race is a social construct — there is no simple way to determine it. It was invented by white people with political, social and economic power as a way to uphold white supremacy. When I call myself white as a person with equal parts white and Asian ancestry, I erase my Asian features under the blanket of whiteness, contributing to racial homogenization and white supremacy. This just further expands the sphere of what is considered “white” and reinforces arbitrary racial categories.

Racial categories are constantly evolving. We are in a time in which the advent of social media allows us to expose ourselves to people of different cultures and ethnicities in a way that was not previously possible. As a result, the discussion and evolution of race is more prevalent than ever, and the discussion we have now and its conclusions will directly influence how we view race in the future. Forcing people of mixed ancestry to choose a race only reinforces white homogenization and the racial categories that we should be trying to dismantle.