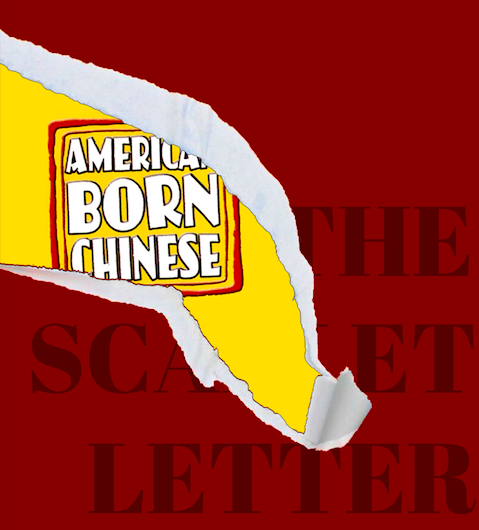

Peeling back the layers: American Born Chinese replaces The Scarlet Letter

Examining how the minority experience is taught by white HAmLit teachers

January 31, 2020

Honors American Literature (HAmLit) teacher Vennessa Nava paces at the front of her room, leading a class discussion on the Asian American experience. She uses students’ personal anecdotes to draw connections to the text, especially because she doesn’t have personal minority experiences. She believes this is a discursive process — the intersection of her literary expertise and the stories of students allow her to teach a deeper exploration of the minority experience, even though she is white.

According to Nava, “traditional American literature” has been novels written by mostly white male authors. Nava and her fellow HAmLit teachers — all three of whom are white — have been focusing on teaching students about the minority experience more accurately. Nava recognizes the demographic of the teaching staff does not reflect the group of students being taught, so she finds that discussions on topics such as the model minority stereotype and white privilege are influenced by her race.

“I find myself going into this meta mode where as a white woman who’s saying this, I recognize that I have privileges,” Nava said. “This year we’ve been reading this piece by a white woman that discusses her reaction to the idea of white privilege, and being really resistant to it initially before understanding it better. In the past, that’s the only piece that we read about intersectionality.”

HAmLit teacher Mark Carpenter also realizes how the Asian American demographic contributes heavily to the class experience. Specifically, there was a stark contrast between traditional American literature and the MVHS demographic.

“The American canon is very white, is very hetero[sexual] and is very cis[gender],” Carpenter said. “Those are not the demographics of the world they live in. Those are not the demographics of the only voices that matter. So there has been a conscious effort on bringing in texts that are more relevant. But the fact of the matter is we have a lot of Asian American students here and we don’t have a lot of Asian American voices in the American lit curriculum and that feels inauthentic.”

This lack of authenticity prompted the HAmLit teachers to add “American Born Chinese”, a graphic novel by Asian American author Gene Luen Yang, to the course curriculum this year. Nava describes “American Born Chinese” as a story about navigating the identity of not being a white male in American society. She believes this piece isn’t as challenging as the ones it replaced — such as Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “The Scarlet Letter”— but is necessary.

“There was ambivalence in terms of making that decision because we recognize that we are sacrificing a degree of rigor for something that’s more in line with the character of the courses,” Nava said. It’s been emerging and evolving. A young adult graphic novel is not on the same rigor level, but I think that it is far more attuned to the experiences of our student population here.”

Although Nava believes that “American Born Chinese” is far more attuned to MVHS, she still finds herself unable to share her own experiences during discussions because she is not Asian American. Junior and HAmLit student Reva Lalwani believes that there are two sides to having non-minority teachers talk about the minority experience. Lalwani views their lack of personal connection with the topic as beneficial because discussions are more objective.

“It’s better in a sense because they’re able to distance themselves from the issue,” Lalwani said. “I’m sure they’ve seen it happen, but haven’t experienced it themselves, which can be good and bad. I feel like as teachers, they need to be teaching the book, not their experience. It’s actually a good thing that they’re able to not become [as] emotional on the topic as someone who is Asian American and has undergone racism would be regarding the same topic.”

Nava believes that because of the large representation of minorities in Cupertino, students have less personal experience with racism, whereas in another part of the country, they would most likely experience more prejudice. In addition, she says that her Caucasian descent makes her feel strange when speaking to students about minority groups in America.

“But then we’re also in this unique place and there is a feeling that there’s a Cupertino bubble,” Nava said. “Many students here, especially if they’ve lived here their whole life, haven’t been exposed to the kinds of marginalization that in other locations in America they might be exposed to.”

Lalwani agrees with Nava in that because of the lack of marginalization minorities face in Silicon Valley, there is a direct affect on the ability to teach the minority experience. Lalwani specifically cites the topic of white privilege as an example of this phenomenon.

“I feel like [the teachers are] obviously more connected to one side than the other because they’ve experienced [white privilege],” Lalwani said. “But because they’re surrounded by Asian Americans in their daily lives, because they teach mostly Asian Americans, they’re able to develop a sympathy and maybe even empathy for the situation. I think they’re able to relate to both sides and because of that, they’re able to give a full perspective on the topic rather than a white teacher in a school full of white kids.”

Nava similarly recognizes that because of her personal connection to issues like feminism, her students can potentially perceive her differently when she talks about it versus when she talks about race.

“There can be this underlying, ‘Well because she’s a woman, so she’s a feminist and talking about all these things about equity and equality,’” Nava said. “In that position, I recognize that my subject positionality means that I could be received in a different way which just doesn’t have to be the case when we talk about race. When we were reading about white privilege, there’s a list of 50 different ways that a white person might not see their privileges. One of them is that as a white person, you can talk about race issues, or you can not talk about race issues. Either way, you don’t need to worry about being seen as self serving.”

Nava calls instances like these — where an instructor seems to have an ulterior motive to teaching the material — a “meta moment.”

“I highlight that item because that’s as a white woman teaching you this, it can be like, ‘Oh, I’m woke,’” Nava said. “But if I were a black woman or a black man, or a different ethnic minority teaching this, you would easily have that underlying idea that, ‘Oh, why is she teaching us this because it’s serving her own individual interests.’”

Nava says that she’s seen a similar meta moment effect on white students in her HAmLit classes during discussions involving race.

“I’ve heard from [white] students in the past … that when we’re in the race unit [they] feel like [they] can’t speak,” Nava said. “They feel silenced, which is very interesting. I don’t want anyone to feel silenced under any circumstances. Yet, isn’t that just a very small taste of what it probably is like, as a minority to feel silenced in certain situations? So I’m not saying, ‘Ha, now you know what it’s like,’ but I’m saying this is just a tiny dose of what is inescapable for people.”

Nava believes that there is still work to be done when it comes to redefining the American canon. She hopes that the adjusted HAmLit content is able to serve not only the student body, but also address the larger concerns of American society. Lalwani is grateful for the curriculum change and says that addressing all sides of America is important.

“I hope we’re able to involve more minority groups, because in our area, I know a lot about Asian Americans, but I don’t know so much about what type of racism other minority groups face, so it would be interesting to pull out different sides and see it from a broader perspective,” Lalwani said.

After having to expand the curriculum to include the minority experience, Carpenter thinks that the lack of staff diversity has become more evident.

“[I] think our staff in general should be more diverse,” Carpenter said. “If we had a future person of color in the English department who said ‘I want to take this course,’ I’d be willing to have those conversations and step down if that seemed to be the right decision to make. I recognize that our staff is less diverse than our student body. And I think that’s something that I do hope changes over time.”