A dead end: Exploring the way mental health issues are tackled at MVHS

Many students don’t take advantage of mental health resources on campus

High test scores, newly renovated facilities and a handful of student wellness resources. From the outside, MVHS seems like the perfect school.

The school’s academically thriving student body, however, isn’t without those who are struggling. Owing to the pressure to fulfill goals and responsibilities — being the perfect student at the perfect school — struggling students today often choose to power through their obstacles without seeking help, at the cost of personal well-being.

In response to these students, the school faculty is making efforts to help by not assigning homework over breaks, being flexible with test dates if students have multiple on one day and providing redemptive opportunities such as test corrections or retakes. Leadership and other clubs on campus host stress-reducing events such as bringing in therapy dogs or plastering posters and flyers throughout the campus to encourage students to reach out to counselors during difficult times.

While these efforts certainly are helpful for some, other students are not as receptive towards them. Hosting mental health days, for example, promotes the value of positive mental health and makes it clear that the school community is receptive of tackling these issues, but these one-and-done events may not directly tackle the problem of specific students who view them and the school’s efforts as futile, or even annoying. Furthermore, while existing resources on campus like counselors and student advocates fulfill an assistive role in the lives of many and are accessible for students in need, they are often unable to fulfill their roles because some students are not receptive towards their efforts.

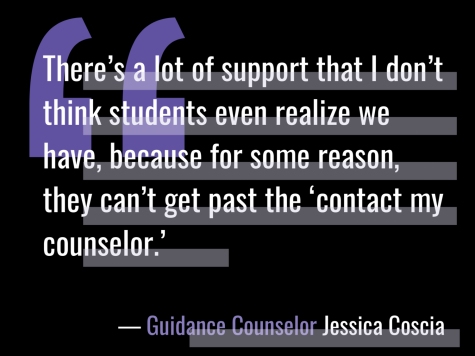

Guidance counselor Jessica Coscia echoes the belief that students often don’t reach out for help even when they need it. In fact, some students and parents are not even aware of the services counselors have to offer, giving them no reason to reach out.

Guidance counselor Jessica Coscia echoes the belief that students often don’t reach out for help even when they need it. In fact, some students and parents are not even aware of the services counselors have to offer, giving them no reason to reach out.

“More often than not, [I] will meet with freshmen and sophomores for whatever reason that they got put on my radar, and they’ll be, ‘Oh my gosh, this is helpful, I wish I would have came like last year,’” Coscia said. “I think it’s that students don’t know what we can do, how we can help or what services are offered.”

Getting one-on-one help from counselors is often not viable due to the overwhelming amount of students each counselor is responsible for. The ideal student-to-counselor ratio, recommended by the American School Counselor Association, is 250-to-1, but at Monta Vista, this ratio is at nearly 600-to-1. Each of our school’s four guidance counselors are overworked, burdened with having to deal with hundreds of different students and constantly addressing a myriad of requests from students and parents.

Our counselors’ overwhelming responsibilities necessitates triage, to some degree, in the way they deal with students: resorting to addressing the requests they receive and being selective by organizing them based on the importance or severity of the student’s concern. Because of the sheer number of students they are responsible for, counselors cannot constantly and consistently reach out to their students, let alone the ones they rarely or never talk to. The guidance department can only guarantee having the time to respond to the students whose scenarios they become aware of, usually through individual requests or notifications from teachers or parents. The large student-to-counselor ratio not only burdens counselors with the exhausting task of managing so many students, but also makes the possibility of receiving help even less likely for students who already don’t feel the need to reach out to their counselors.

“It’s like in a classroom: if you’re struggling in math class, you know that your teacher’s there during lunch, your teacher’s there during tutorial and your teacher is willing to help, but if you’re not going in for the help, it’s not going to work,” Coscia said. “We try to see as many students as we can, but if students aren’t reaching out, then we may not know that they need help.”

“It’s like in a classroom: if you’re struggling in math class, you know that your teacher’s there during lunch, your teacher’s there during tutorial and your teacher is willing to help, but if you’re not going in for the help, it’s not going to work,” Coscia said. “We try to see as many students as we can, but if students aren’t reaching out, then we may not know that they need help.”

Efforts are being made by the guidance department, however, to maximize the potential of the time that counselors have to benefit as many students as possible. Coscia, for example, keeps an open-door policy in her office, especially during the busiest times of the year, so students can ask brief questions and avoid the often lengthy and inconvenient process needed to schedule an appointment.

Despite their busy schedules, counselors still make committed efforts to meet the requests of each student, even if they might not be able to respond immediately.

“I’ve never had a situation where I’ve had a student say, ‘I tried to get ahold of you and we never met,’” Coscia said. “I’m always able to see all the students, or at least [respond to] their emails.”

MVHS’s student-to-counselor ratio also potentially discourages students from being proactive in reaching out to their counselors. Believing that the intimidating ratio renders requests futile because counselors may not have enough time to address their troubles, students often choose not to receive help at all. Their inaction spirals themselves into a dilemma of whether to keep their troubles to themselves or to reach out for help.

MVHS’s student-to-counselor ratio also potentially discourages students from being proactive in reaching out to their counselors. Believing that the intimidating ratio renders requests futile because counselors may not have enough time to address their troubles, students often choose not to receive help at all. Their inaction spirals themselves into a dilemma of whether to keep their troubles to themselves or to reach out for help.

Part of this decision is cultural too; the pressure-cooker environment of MVHS causes some students to overlook the services offered by school counselors and advocates. Many are often driven by the idealism that grit and taking personal responsibility for one’s own emotions and workload are essential, even if it could result in self harm. Being from a culture where admitting vulnerability is inacceptable creates an unhealthy space where students feel deterred from asking for help and scared of potential humiliation from their parents or peers, even in situations where it’s most needed. While life skills like grit are necessary for being successful in the future, they should not extend so far as to dictate how we approach our mental health. Taking responsibility for ourselves is important, but our school’s resources are here to provide just that.

“When a kid comes in crying, I’m not going to say, ‘Man up, you can handle it, you’re fine’ — I’m going to hear [them] out, we’re going to talk, and I’m going to make sure [they’re] okay,” Coscia said. “I think it’s important for students to take responsibility and think about their emotions, but we don’t expect high school students to handle that on their own. We know that you’re going to need encouragement and you’re going to need time; [this skill is] something that you build over your entire lifetime.

“When a kid comes in crying, I’m not going to say, ‘Man up, you can handle it, you’re fine’ — I’m going to hear [them] out, we’re going to talk, and I’m going to make sure [they’re] okay,” Coscia said. “I think it’s important for students to take responsibility and think about their emotions, but we don’t expect high school students to handle that on their own. We know that you’re going to need encouragement and you’re going to need time; [this skill is] something that you build over your entire lifetime.

To build on this skill, students should better take advantage of the resources in their lives — counselors, parents, favorite teachers, therapists or religious advisors. Especially at school, students should utilize the resources offered to receive guidance on the minutiae of stress and how it stems from different causes. The academic and social-emotional support offered by guidance counselors and student advocates can facilitate healthy discussion on the topic and allow students to comfortably share their concerns, whether their parents and peers approve of this vulnerability or not.

Combatting stress isn’t one-dimensional; as a systemic problem in our community, tackling the issue requires collaboration between everyone — students, administrators and parents — to address all of its nuances. Aiming to relieve overworked counselors on the district-level through any means, such as bringing the student-counselor ratio closer in line with the recommended 250-to-1, can help them deal with an often heavy workload and better serve their students from a proactive angle.

But there are also issues coming from the parents of these students; the actions of parents who are constantly worried to the point of drone-like surveillance indirectly exacerbate the problem of mental health at MVHS — many of them continue to send their children to SAT classes or dismiss mental illness as something trivial and not to be dealt with properly. Parents could instead tackle the issue more effectively through finding help from therapists or similar modes of emotional treatment.

However, it ends up ultimately being the actions of students themselves that continue to indirectly inflict stress on them. Sidelining mental health for other commitments and not seeking help isn’t sustainable in the long term for their well-being. Students have to be willing to make the necessary changes in their behavior, such as taking the school’s resources seriously and limiting the number of stressful APs they enroll in, in order to set up healthier circumstances for not only themselves, but also MVHS as a whole.