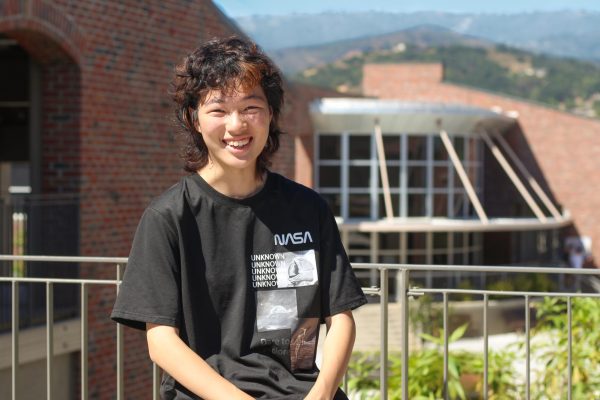

While watching HBO’s “Game of Thrones,” English teacher Jessica Kaufman recalls enjoying the progression of one of the series’ most controversial figures: Jaime Lannister, who entered the series in season one with an unapologetically villainous bang. From committing incest to defenestrating a 10-year-old from a tower, Kaufman sums up his actions as “pretty screwed up” at the beginning. However, in the context of the story, the scenes felt striking and purposefully twisted, befitting her vision of a well-written villain character.

“I do appreciate the discomfort,” Kaufman said. “Villains don’t have to be scary, but they have to make you uncomfortable for some reason. I think that villains should have depth and not be flat characters that are just like, ‘Oh, you’re evil for the sake of being evil’ — there’s some dimension to them, and a relatability in that dimension, on some level, to humans.”

According to author Robert McKee in his book, “Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting,” a protagonist can only be as “intellectually fascinating and emotionally compelling as the forces of antagonism make them.” Starting with the Epic of Gilgamesh — often regarded as the earliest known piece of literature in the world — heroes and their antitheses have played out and expanded on these roles. Despite the evolution of villains between then and now, junior Cyrus Mazdeh finds that their purpose in each story remains straightforward.

“The role of the villain, it’s a few things,” Mazdeh said. “Entertainment — who would watch a movie without a villain? It’s boring. The next reason is, I think they try to use a villain to make the main character look good, and there needs to be a roadblock in the story and a climax, but movies and TV shows really need to focus on the villain. They need to give them enough time so they become their own character.”

Mazdeh notes that realism isn’t essential to his appreciation of villain characters. Conversely, complexity does matter. To explain the difference, he recalls the fictional antagonist Bowser in “The Super Mario Bros. Movie,” who raises an army of Koopas to raze Princess Peach’s kingdom, as one instance of an unrealistic yet compelling villain, humanized by his struggles with unrequited love. Pure evil villains entertain Mazdeh, but he and Kaufman agree that the lack of emotional relatability hinders their ability to care for such characters.

Each year, seniors in Kaufman’s Mythology class delve into the implications of villains by studying Bram Stoker’s “Dracula,” a novel she describes as “hugely reflective of Victorian repression and fears and xenophobia.”

“The whole unit in Myth that we do is about how monsters and villains reflect the fears of society or some of the taboo subjects that we should talk about, but don’t, because we’re repressed,” Kaufman said. “Villains tend to embody those things and allow us to look at them in a socially acceptable manner, and I think that’s really cool. But I think that, in order to do that, they have to be somewhat relatable. If they’re completely alienating, then you don’t care.”

Like Kaufman and Mazdeh, junior Trisha Akhare finds moral complexity intriguing in fictional characters, especially since most of the films she watches do not revolve around clear-cut heroes and villains. One exception is the live action “Maleficent,” which Akhare enjoyed because it humanized the classic “Sleeping Beauty” villain and enabled her to understand and empathize with Maleficent’s motivations.

“Generally, villains are really overexaggerated,” Akhare said. “They convey the message in an easy to digest way. I think the benefit of overexaggeration is that it’s better when people have to actually think about the message of the piece of media.”

However, Akhare finds that the use of shock value to achieve this message can become excessive, especially if its only purpose is to make the film “gritty and dark.” For instance, Akhare disapproves of rape scenes as they are often directed by men, executed insensitively and neither add to the plot nor further discussion of the topic. To Akhare, such scenes are never necessary to develop a character, no matter how villainous they are.

“In film, it’s easy to make it evident what the characters’ inner desires and thoughts are, and that is what makes good storytelling, not just showing their bad actions,” Akhare said. “The topics, like discussing the idea of it, does bring the plot forward, but I don’t think depicting it makes it more impactful. I don’t think media should be expected to carry a message through violence or depictions of violence.”

Likewise, Kaufman believes gratuitous depictions of violence and evil are a cop-out for creating complex villain characters. To Kaufman, Jaime Lannister’s initial villainy set the stage for his later development, often hailed as one of the most satisfying redemption arcs in media. However, many later screenwriting choices in “Game of Thrones” veered into what she views as meaningless violence, altogether leaving a sour taste in her mouth.

Akhare also notes that villains often resemble negative stereotypes associated with marginalized groups. For instance, she recalls reading an article on how past Disney villains have been queer coded (Ursula from “The Little Mermaid” was based on drag queens) or perpetuate ethnic stereotypes (evil characters such as Jafar, Shan-Yu and Mother Gothel tend to suffer from exaggerated ethnic physical features), while Disney heroes and protagonists tend to be elegant and white. Akhare explains that these tropes send a clear message to their audiences, affecting young children in particular.

“America prides itself on everyone being equal, but then they see these things and it’s worse when there’s an undercurrent of racism more than outright,” Akhare said. “Because then these children will carry these beliefs that their race is inherently bad, and they won’t even know until they get the chance to dismantle it, which sometimes is never.”

The characterization of Count Dracula references topics considered taboo when “Dracula” was first published in 1897, including female sexuality, homosexuality and race. Kaufman explains that an important takeaway from the “Dracula” unit in Mythology is that villains and monsters in fiction are fundamentally an outlet for human fear. This role can enable negative stereotyping, as with historical Disney villains taking on the racist stereotypes of the times, but as readers examine characters like Count Dracula, villains can also provoke deeper conversation about what society deems evil.

“There’s a psychology behind villain characters that causes us to question on a deeper level, even if it’s subconsciously, what we’re actually afraid of,” Kaufman said. “When you get scared of something, especially repeatedly or something bothers you, you shy away from it. But then at the same time, you also think, ‘Why do I shy away from that?’ Monsters reflect our culture at the moment in time that they are created, and the moment in time you study it, and the moment in time that we relate to them.”