S: Hi, I’m Sarah.

M: Hi, I’m Michelle.

S and M: And today, we will be discussing linguistic stereotyping in movies.

M: We’ll be exploring how the use of language stereotypes in movies has evolved, and discussing whether these changes have been beneficial or harmful. Let’s start with listening to a few examples.

S: This first clip is the audition for the Siamese cats who serve as minor villains in Disney’s “Lady and the Tramp.”

M: Without even seeing the blatant, stereotypical Asian features in the Siamese cats, you can already identify the stereotypes after hearing the heavy “Asian accent.”

S: It’s obviously a caricature of Asian accents with the annoying high-pitched voice.

M: Furthermore, as both of the cats say the same words and have the same voices, the speech of these cats serves to perpetuate the stereotype that all Asian people have similar characteristics.

S: I was also thinking the same thing when I first heard this. Especially since the Siamese cats have extremely generalized rather than authentic Thailand accents, Disney essentially erases linguistic distinctions between different Asian groups, reinforcing linguistic stereotypes.

M: Besides misrepresenting different cultures, I also see a recurring theme of villains or animals having racial accents in Disney movies.

S: Now that you mention it, I remember in “Mulan,” the dragon Mushu speaks with African-American Vernacular English, or AAVE, which is a North American dialect of English used primarily by African Americans.

M: However, the main characters Mulan and Shang use Standard American English or SAE.

S: This is noteworthy because the use of AAVE only for animals perpetuates an association between AAVE and inferiority, leading to a subsequent association between people who use AAVE and a similar sense of inferiority. Often, the characters using AAVE are characters providing comedic relief, normalizing the appropriation of this dialect while conveying a negative connotation of the racial groups who use AAVE. In “Mulan,” for example, Mushu, the primary comical character, uses elements of AAVE speech while no other characters use accented speech.

M: When only the villains and comedic sidekicks are given the accents, it pushes a standard language ideology onto young audiences — who are also impressionable. Young children watching these movies may associate these linguistic stereotypes with actual people, reinforcing racial inferiority.

S: Now, that’s not to say we should eliminate all race-based types of English in movies. When done correctly, having characters use accented English can actually be beneficial for the message of the movie. For example, “Coco,” uses Chicano English authentically and educationally rather than for comedic purposes.

M: Most importantly, all characters in the movie have accented speech, rather than just the villains or the comedic sidekicks. Thus, characters using Spanish-influenced English do not stand out negatively. Instead, they’re seen as the norm, providing an accurate representation of aspects of Mexican culture.

S: Going forward, it’s important for us to be aware of these linguistic stereotypes in the media we consume. At MVHS, we live in a predominantly-Asian community, so it’s obvious to us that these linguistic stereotypes of Asian speech are untrue and exaggerated. However, because there is less representation of people who use Chicano English or AAVE speech in our community, we may not be able to identify whether accents and linguistic traits in movies are actually authentic or just stereotypes.

M: Thus, when watching older movies, we should learn to differentiate between an authentic representation and the usage of stereotypes in their language and understand their significance in a modern context.

S: Well, that’s it for today!

M: And this has been—

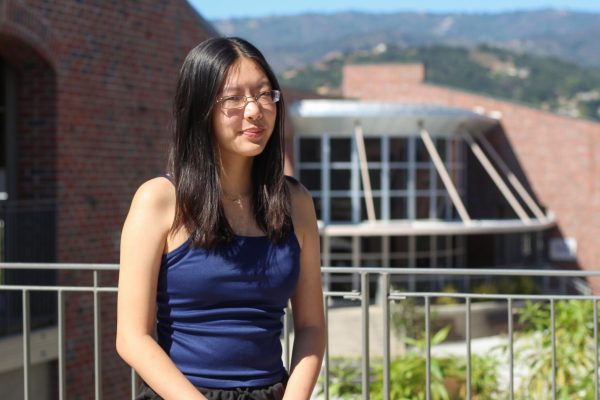

S: Sarah—

M: And Michelle!