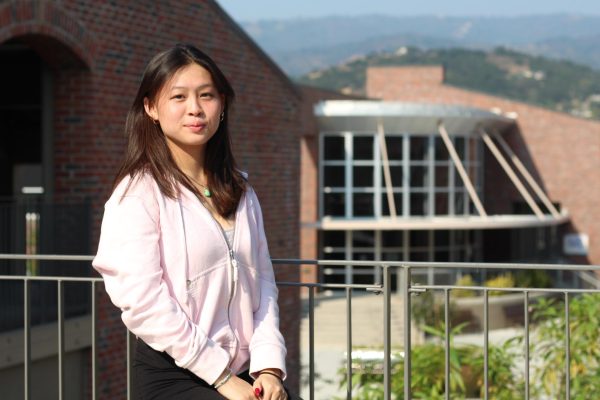

Spanish and French teacher Joyce Fortune began to notice that there was an issue with her vision in elementary school. However, due to the rarity of her condition, Fortune’s doctors could not properly diagnose her. It wasn’t until she turned 16 that she was diagnosed with macular degeneration, a rare eye condition in which the center of the retina have pigment cells that over-produce pigment. This damages the sight cells, causing central blind spots and affecting vision over time.

“When I was born, my eyes were clear, but then it got worse over time,” Fortune said. “For me, it was awesome [when I was diagnosed] because then I knew it wasn’t my fault that I couldn’t see.”

Fortune’s condition impacted her high school experience because her vision presented additional hurdles to overcome. For instance, she felt alienated from other students her age because there were simply things she couldn’t see.

“[Throughout] my childhood, I always felt really outside of people in groups, because there’s a lot of clues that I wasn’t getting [and] things I wasn’t seeing,”  Fortune said. “I remember walking down the hall in high school and I would walk with my friend Michelle, who would tell me who was coming so I could say hello [to them].”

Fortune said. “I remember walking down the hall in high school and I would walk with my friend Michelle, who would tell me who was coming so I could say hello [to them].”

Though Fortune struggled to navigate her school life with her visual impairment, Fortune’s mother chose to keep her out of special education classes, due to her mother’s stigma against special education. Though this helped Fortune learn the importance of independence, Fortune also found it difficult to ask for help.

“I was at Stanford in my freshman year and I was in Western Culture and I had to read hundreds of pages a week, and I just was like, ‘I can’t do this anymore,’” Fortune said. “And I was reading Augustine’s Confessions, which is a super boring book and it has a lot of italics. And [reading] italics [is the] worse for me to try and figure out. So I went to the Disability Resource Center and said ‘Help’ and cried, because I had never really asked for help.”

Afterward students came in to read textbooks aloud to Fortune, which helped her throughout college. After this experience, Fortune realized the importance of advocating for her needs.

“When people are [legally] blind, you know what they see, and when people are fully sighted, you [also] know what they see,” Fortune said. “When people are visually impaired, it’s hard to know how much they see and how much they don’t see. [For example,] my husband [and I] have been together for 27 years and he still doesn’t know what I see and don’t see. So [usually,] people think I see better than I do, because most of the time I’m pretty highly functional. That’s kind of the frustration — I know you think I’m fine, but I’m really not.”

Due to Fortune’s visual impairment, she asks teachers to proctor testing periods for all of her classes. Because of this year’s declining enrollment, Fortune has struggled to find teachers, and is currently still looking for one for fifth period.

year’s declining enrollment, Fortune has struggled to find teachers, and is currently still looking for one for fifth period.

“I’m still looking for a fifth period teacher [because] everybody’s busy and I understand that people aren’t available but it’s this angst because I don’t want to give tests that are easy to cheat on,” Fortune said. “ I need to solve this, so this may be something you might hear a lot if you talk to people with disabilities: it’s not my fault but it’s my problem. I have to fix this problem even though I didn’t cause it.”

Despite the challenges, Fortune finds joy in various activities such as traveling, something that she and her husband James Tank love. Tank notes that Fortune’s ability to speak multiple languages, such as French, German and Swedish, have especially helped during their travels to Europe.

In addition, Fortune enjoys doing contradancing, as well as listening to audiobooks and has influenced her family to take on this hobby as well. Her daughter, Nikki Tank, says she uses the audiobooks for homework readings and during commutes.

“We listen to different books [because] it’s 45 minutes of listening [driving] in to work and 45 minutes of listening going back home — that’s what Joyce has introduced to the family,” James said. “Some of Nikki’s school texts are on audio, so she can listen to [them] too.”

However, there are some struggles the family encounters as a result of Fortune’s visual impairment. For example, when Nikki needs help for homework, it can be difficult for Fortune to assist her, especially because Nikki has dyslexia. Nonetheless, James and Fortune continue to build happy memories together through the challenges Fortune faces.

“[My favorite memory] is probably sitting by the campfire because we have a firepit,” Nikki said. “[Fortune] will see the glowing of the fire and she loves the fire. We all just sit together on the couch and sometimes the dog will jump up. We just like doing that because we all see the fire and the beauty of the backyard.”

Fortune hopes that people can understand that individuals with disabilities have different experiences and recognize that all individuals have their own unique needs. In addition, she values the importance of individuals who have challenges they deal with to stand up for themselves and ask for help.

“We all have things that make us different, that are different from the world around us,” Fortune said. “And we have to step up and say, ‘This is what we need,’ ‘This is how I’m different,’ ‘This is what is important to me,’ ‘This is how whatever you did was problematic’ or ‘This is how I need this service or support.’”