A thin line

Exploring student and staff perspectives on artificial intelligence art

AI art has raised fears of human artists being replaced by machines.

March 12, 2023

When junior Medha Singamsetty first saw art created by artificial intelligence, she remembers feeling frustrated — not because the program had produced “people with four fingers and six fingers” and their “faces melting off,” but because she saw the AI’s potential to steal the work of human artists.

“[AI] is a valid way of creating something, but [shouldn’t be passed off] as art,” Singamsetty said. “It’s like if you commissioned an artist, and they made something for you, and [you] said [you] made it. In this case, it’s even worse than that, because it’s taking the art of people who didn’t agree or ask for [it to be used] as data for this machine to make something.”

AI art models generate an image from a text input by training datasets of preexisting images to recreate objects, colors and art styles. Although AI art has existed since 1973, the technology has recently taken center stage with the public release of tools like DALL-E and Midjourney, and the introduction of AI art filters on apps like TikTok. Art teacher Brian Chow attributes AI art’s recent popularity to its accessibility, as anyone can produce a piece of art in seconds after typing a few words.

“The AI feeds into that [instant gratification],” Chow said. “I want what I want when I want it, and I want it to be like this. If the automated artwork can be made, why do I have to go buy it from that company? I get [it] cheaper over here.”

Student artist and Cupertino High School senior Anika Verma adds that AI art has the potential to be a valuable shortcut for artists.

“[Artists] enjoy automated things,” Verma said. “We enjoy in-between framing applications. The problem is that the datasets that are used to teach AI are not [used with] permission.”

Image generators have faced criticisms from artists who found their work was used to train AI, although the actual images the programs use are usually not public. Singamsetty believes the issue “lies with the tool itself” and that AI art needs to credit or compensate artists, with Verma adding that programs should commission artists to make datasets.

In response to these criticisms, some image platforms, such as DeviantArt, have implemented an opt-in system where artists consent to having datasets use their art. Other platforms like Shutterstock plan to sell AI images and “provide additional compensation for artists whose works have contributed to [developing] the AI models.” However, while senior and AI club co-president Saloni Gupta believes compensation is important, she says it can be difficult given how AI art generators work.

“You can put in many words and make the image completely unrecognizable,” Gupta said. “So it’s really hard to understand if there’s any copyright issue. I think the best way is that once you [generate the image], they require that you make a part of the image to be like, ‘These are the credits of the artists.’ [But with] thousands of images, [the art is] a whole new thing that I bet the artist wouldn’t be able to [recognize].”

On the other hand, Verma says the possibility of AI art generators not just exploiting artwork but also completely replacing human artists has become an increasing concern within the art community.

“Initially, the art industry brushed AI art off because it was pretty janky,” Verma said. “Recently, it has proven to be more useful, to be able to replace artists. It’s obviously stirred a lot of fear. I mean, I’m a student. I’m not in the industry, [and I’m] scared that it could take away certain jobs that I was prospecting before I’m even in there.”

Beyond the effects on artists, there are fears that AI-generated images can also have widespread negative effects on society by allowing the creation of deepfakes and explicit images. Gupta maintains that users should not be allowed to produce such visuals as it crosses into “dangerous territory where you would be allowed to create whatever you want,” citing DALL-E’s AI art content policy as an example.

Chow finds the possibility of deepfakes alarming, but he doesn’t think AI art generators will be able to completely replace human artists due to their reliance on pre-existing artwork. However, he says AI fits into his definition of art as a form of expression that challenges human thinking.

“Artists will be artists,” Chow said. “The tools they use might look different or [take] different forms. The outcomes of their work might look different. But the data still serves the same purpose, the human expression [and] recording history. It’s sharing ideas and communicating how we feel and sparking interest in inspiring us to move, to act.”

Although Verma maintains that AI art could still help make work easier for artists in the industry, she thinks AI art should not be considered real art – not only because of ethical issues, but also because it lacks the “element of connection” human art has.

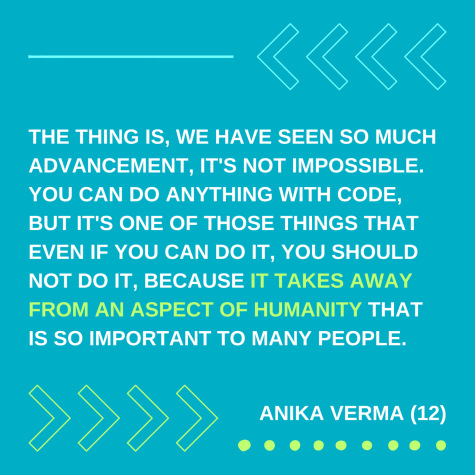

“Slowly we’re realizing that [AI art] is not a tool,” Verma said. “They’re trying to turn [it] into a replacement. And the thing is, we have seen so much advancement, it’s not impossible. You can do anything with code, but it’s one of those things that even if you can do it, you should not do it, because it takes away from an aspect of humanity that is so important to many people.”