Expanding past size zero

The consequences of corporate resistance to include diverse body types

The concept of “one size fits all,” predominantly oriented around one size fitting smaller bodies, is harmful.

October 9, 2022

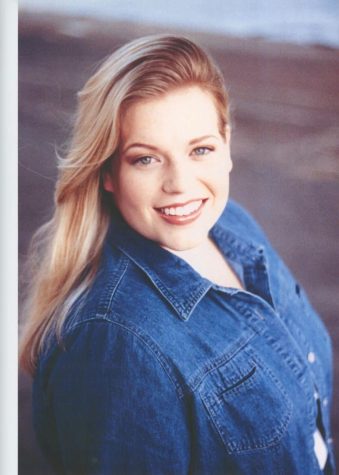

While attending St. Louis University in the late 1990s, history teacher Bonnie Belshe received a call from a representative at Liz Claiborne, a popular fashion brand at the time. Belshie believes a classmate’s mom referred her to the representative, who offered Belshe a position as a model for Liz Claiborne’s plus-size clothing line “Elizabeth,” based in St. Louis.

Fashion at the time was, according to Belshe, “all about being as thin as possible,” so Liz Claiborne’s decision to create a series of “plus-size store[s] was huge because [there] were so few options available in plus sizes, and there were so few models representing bodies that were above a size zero.”

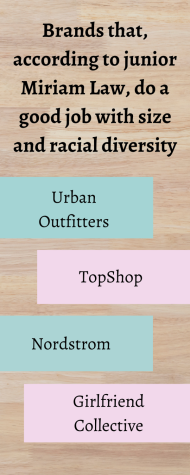

Senior Jeremiah Moli believes the fashion industry has progressively expanded the range of models concerning ethnicity and size. Junior Miriam Law agrees with Moli, attributing brands such as Urban Outfitters, TopShop, Nordstrom and Girlfriend Collective with having diverse model demographic and sizing. However, Law also believes that, despite brands getting more inclusive, there are still areas where the fashion industry can diversify.

“Sometimes brands like Victoria’s Secret — [that] fall into the more intimate side [of clothing] — prefer [specific] models or specific sizes,” Law said. “And that goes against the whole [concept of] diversity.”

Victoria’s Secret is one brand that, according to Law, has failed to incorporate diversity. But, due to this lack of diversity being present across many clothing companies, not only is the selection for clothes much narrower for plus-sized individuals, the clothes also tend to fall behind in trends and, according to Belshe, consistently have an unflattering appearance.

“Some [brands’] plus-size [clothing lines have] absolutely horrendous clothing,” Belshe said. “[There are so many] cold-shoulder shirt[s] for plus size women — you only see these for plus sized women, where it would be [a] jacket [with] just the shoulder [region cut out] — because heaven forbid any other part of our body show.”

Furthermore, according to Moli, in terms of diversifying the modeling demographic of the fashion industry, body positivity has come a long way since the 1990s and early 2000s.

“There’s a trend of inclusivity when it comes to [body positivity, where companies are] getting different models who are of different shapes and sizes [to diversify the representation on their website],” Moli said, attributing brands such as Nike and Puma to being part of this growing “trend.”

In particular, Law states how the transition into brands representing diverse bodies conveys that being plus-size is just as acceptable as being petitie or mid-sized, and being a person of color is just as acceptable as being white. Law also says that companies who portray both these concepts appeal to a larger audience.

“I feel more comfortable buying the clothes [from companies that include body diversity], especially knowing that they don’t have implied expectations for people who are buying them and consumers in general,” Law said. “Especially because I don’t fit into that typical white model [that] a lot of websites like to portray… [Having diversity is] a good way of marketing in my opinion.”

However, Moli also states how, despite the industry getting more inclusive in the past decades, “there’s [still] an aspect of favoring a specific type of [models]: the heterocentric, [which is] women are white, [and] typically more fit.” Belshe agrees with Moli, stating how the model demographic for plus-size models remains “overwhelmingly white, even more so than [for] straight sizes,” which demonstrates how many brands have begun creating an inverse relationship between racial diversity and size inclusivity.

Belshe explains that she believes this is because the post-Civil war period warped society’s perception of plus-size Black people, particularly plus-size Black women.

“Part of the stereotype that was created around Black women [after the Civil War] was [the creation of] the mammy figure — an overweight Black woman who is completely desexualized,” Belshe said. “And then there are a lot of other cultural elements for looking at why we don’t have East-Asian and South-Asian representation. [Then, there’s] the difficulties for plus-size women in those cultures and societies not having access to a lot of the fashion that’s available. And so we see [all these cultural and social differences come together and be] reflected in [the] U.S. fashion [and modeling industries].”

According to Moli, racism is still deeply ingrained in the modeling industry. Moli explains that many corporations include diversity purely to expand their consumership, which Moli explains is counterproductive as it leads to people of color and plus-sized models being tokenized in the modeling industry.

“[Companies are] using the trend of body inclusivity to sell their brand,” Moli said. “Because they [think if they’re ‘safe’] towards what people are leading to then we can sell more and avoid the controversy of pushing out what people aren’t liking. So I feel like they’re exploiting [the social movement]. And perhaps even exploiting people just [for diversity] … it’s like, ‘Oh, they’re exotic!’ and I feel like that aspect is taking away from the expression of fashion and [putting models on display] like they’re zoo animals, to an extent.”

Though the concept of the “model body” has slowly waned throughout the years, Moli and Law believe the industry continues to glamorize skinnier bodies. Belshe adds how a large portion of recent body positivity campaigns only go up to mid-sizes at best, excluding plus-sizes while continuing to showcase models with smaller sizes — many major corporations forget to incorporate genuine size diversity in their body positivity campaigns.

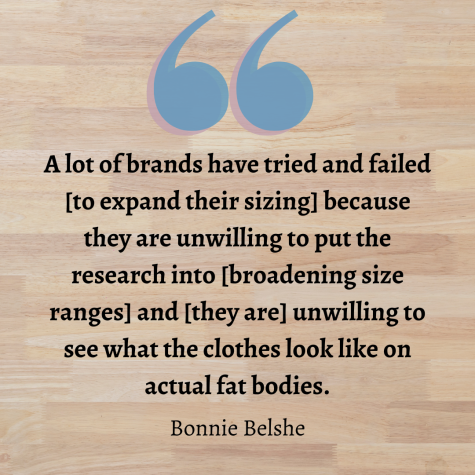

“What they call ‘plus size model’ is not even into mid-size[s],” Belshe said. “[Brands] don’t always do plus sizes correctly — you can’t just size up everything. You can’t just make it all longer and wider. [For example], if you have to double the size of the chest of a shirt, you [can’t] also double the size of a wrist. You have to think about the proportions for [sizing]. A lot of brands have tried and failed [expand their sizing] because they are unwilling to put the research into [broadening size ranges] and [they are] unwilling to see what the clothes look like on actual fat bodies.”

According to Belshe, the overrepresentation of predominantly skinny models on fashion websites is particularly dangerous for younger, more impressionable individuals.

“Not everyone is going to have [a] body [that fits a size zero],” Belshe said. “And it’s not achievable, nor [is it] healthy for many people [to try]. And I’m not saying [that] someone who [is] thin is unhealthy. But the ways in which many — young women especially — try and go about to achieve that ‘model body’ is incredibly damaging.”