Displaced by war

Ukrainian students share about their evacuation experiences

Sonya Povalchuk and Pavel Demchenko share how they evacuated Ukraine.

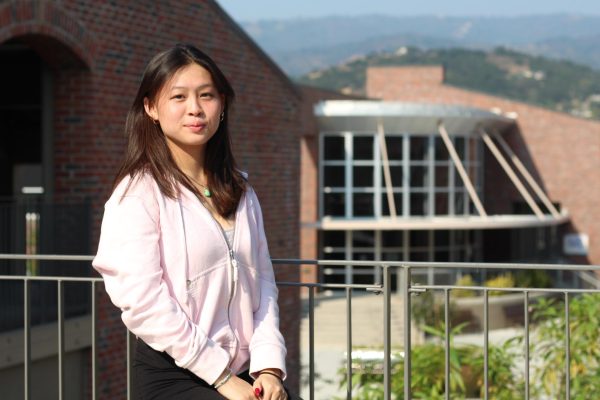

Sonya Povalchuk

For sophomore Sonya Povalchuk, the morning of Feb. 25 started with two loud explosions. Although she felt like the explosions had taken place in her own backyard, she later learned that they had taken place near her. Before Russia invaded Ukraine, Povalchuk “[lived] like a traditional student” and found that her life was “wonderful.” She went to school, went on walks with her friends and volunteered at the local YMCA.

“After [we heard the bombs] my mom and father [said] that it [would] be safer for us to go into another country,” Povalchuk said. “We [decided that] Poland was the [best place] for us to go. We started right away and we packed our bags in one hour. I [had] one bag, my brother [had] one bag and my mom had one bag.”

Due to the martial law in Ukraine, which restricts men aged 18 to 60 from leaving the country, Povalchuk and her family had to leave their father behind in Ukraine and make the journey to Poland with a close family friend. Povalchuk left Ukraine hastily and expected to reach Poland the same night. However, extreme traffic conditions meant that they could only travel one kilometer every four hours. The 30-kilometer journey across the border took five days. Because of the unexpected traffic, Povalchuk and her family had no food on the prolonged trip.

“It was [a] problem that we [couldn’t] eat but there were a lot of people volunteering and they [were] giving us soup and sandwiches,” Povalchuk said. “[Back then] we [slept the] first night in [the] car and it was difficult because in [the] little car, [it was] two adult women, and six children.”

While Povalchuk says she appreciates the support that Ukrainians have been receiving, she doesn’t want foreigners to antagonize Russian people. Instead, she wants to spread awareness and wishes for “people to know about this conflict.”

After arriving in Poland, Povalchuk lived at a hotel in Poland for over a month. For her education, Povalchuk goes to a local Polish school during the day and attends a Ukrainian online school at night.

“I speak only in Polish because they can’t understand English and they [have a] difficult [time] understanding Ukrainian,” Povalchuk said. “[I chose to go to school in] Poland because [it’s hard to] stay at home and it’s very difficult to hear and swipe on news when my father is still [in Ukraine].”

From her experience with the Ukrainian crisis, Povalchuk has realized that she doesn’t miss the material things in life, but instead “[misses her] father and [her] cat, Thomas.”

“[Americans should] be more polite [towards their] mother, father [and] friends,” Povalchuk said. “I [didn’t] think about it when it was all OK. Now I have a problem because I miss [many] people and it’s very strange for me. People who are [your] soulmates, spend a lot of time with them.”

Overall, Povalchuk believes that people need to advocate for Ukraine’s membership in NATO, because she believes that “if [a] very big group of people from [the] UK and USA will talk about it, NATO will start to think about [accepting Ukraine into NATO].”

“[My hope] is that all attacks from Russia will end and this [war] will end for us,” Povalchuk said. “I [want] to come into my home in Ukraine and re-build our buildings and houses. I hope that Russia will change presidents because with this president, we will [never] have peaceful skies.”

Pavel Demchenko

On March 19, sophomore Pavel Demchenko, born in the separatist region of Donetsk, Ukraine, evacuated Ukraine to be able to continue playing ice hockey and follow his dream of becoming a professional ice hockey player. After the Ukrainian Federation allowed him to leave, he took a bus to Romania with his coaches and teammates. Originally, Demchenko was not worried about the Russian invasion and helped his friends gather supplies in preparation for attacks. However, he now feels broken-hearted about the damage to his country.

“It is scary [to see] how many cities, parks [and cultural structures are now] crushed,” Demchenko said. “It is so sad because you [saw them as] beautiful places and now you see photos [of them destroyed].”

Demchenko left his home in Kharkiv at night and traveled on a bus with his teammates to the city of Chernivtsi near the Romanian border. After staying in a hotel for three days, the team made its way across the Romanian border and south to the city of Brasov. Demchenko is grateful for the welcoming nature of the Romanian people.

“I am now in Romania, and people help us buy all we need,” Demchenko said. “I would like to say thank you for that because we [received] emergency bags, t-shirts, trousers and [everyone] helped us [find a home] and [provided us with] training.”

In Romania, Demchenko doesn’t attend school and instead “trains and coaches” during the day, and describes the experience of living and working with fellow Ukrainians as “very fun.” Despite the poor internet connection in the hotel, Demchenko still manages to communicate with his family, who stayed behind in Ukraine, via a mobile phone with a SIM card and through the messaging apps WhatsApp and Viber. Demchenko knows some Romanian, but to communicate with locals, Demchenko relies on his knowledge of the English language, which he finds to be extremely useful.

While Demchenko misses the “culture and people” of Ukraine, he is grateful for his experience in Romania and finds the people to be “very friendly.” One issue he currently struggles with is a lack of schooling, even online, because his teacher in Kharkiv is preoccupied with volunteer work. Demchenko is now looking for a school to attend in Romania. His experience with the evacuation has taught him the importance of making the most of the limited time available, and he hopes to share what he learned with those in other countries.

“People need to talk more [and] spend more time together, while [they] can,” Demchenko said. “Life [can be so] easy, and [then] one situation can transform your life, and you need to be ready for this.”