Culture and the future

How MVHS student and staff expectations of the future are affected by cultural and religious factors

November 12, 2021

Annie Roe

Despite moving from Korea to the U.S. at 10 years old, psychologist Annie Roe continues to feel the rooted presence of Korean culture and tradition. Roe’s parents both graduated from Seoul National University, the No. 1 college in Korea, and Roe says her parents thought the only way for her to be successful in the U.S. was to follow a secure career path. However, she opposed her parents’ wishes and didn’t aspire to become a doctor or lawyer — the top job contenders in their eyes.

Before she was born, Roe’s parents had gone to visit a fortune teller in hopes of selecting a name based on her birth date and the moon cycle that would accurately represent her future. In the end, they settled with Young Yim.

“Young is supposed to mean ‘swim,’ as in getting over obstacles in life,” Roe said. “Yim is supposed to mean duties and responsibilities. So the name is supposed to mean going through all of the obstacles in my life dutifully and responsibly.”

Roe’s parents also held a Doljabi ceremony for her — a common Korean tradition celebrating an infant’s first birthday. The festivity includes a lighthearted custom where the child is exposed to a variety of objects and is told to choose one. The chosen item is then said to determine their future career path or lifestyle. Although Roe doesn’t remember her Doljabi, she recalls a photo of herself “pulling [her] hat off because it was itchy, and [using] a pencil and a pen to try to get the hat off.”

Typically, infants choose only one item — Roe chose two, however, both of which represent pursuing education and being intelligent. Despite undergoing the ceremony, Roe still resonates more with her name than her Doljabi, as she feels like she “did well” overcoming the challenges in her life as an immigrant. Still, she has reservations about traditions that predict a child’s future.

“Just because you grabbed a pen or a pencil doesn’t mean you can’t be the person that grabbed the money,” Roe said. “You can have these fortunes but you can [also] become wherever you want to be.”

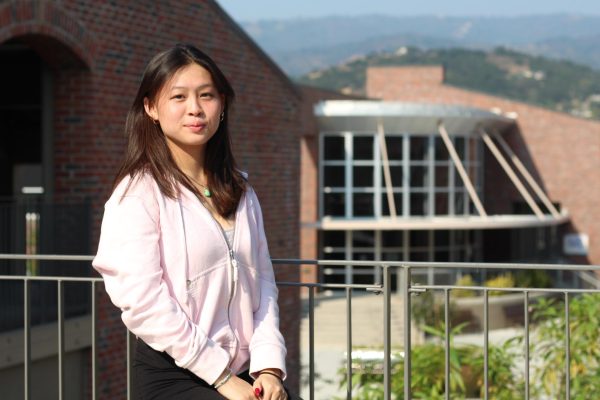

Renee Ou

Heaven and hell — two ideas of Christianity that senior Renee Ou says have become oversimplified into a “good place” and a “bad place.” For Ou, there are more factors involved than simply being a good and bad person. She believes people don’t have to “necessarily live a perfect life” to go to heaven. Rather than focusing on the complicated future of heaven and hell, Ou says that she doesn’t “dwell too much on the concept of hell.”

“I want everyone to be in heaven,” Ou said. “If somebody talks to me about what it’s like being a Christian, I don’t want to be like, ‘Here’s hell, and it’s this terrible place,’ because it doesn’t really give people that much hope. So I would like to focus on the positives and talk about how being a Christian has impacted me rather than just heaven and hell, because I think that a lot of the things that we do as Christians impact the material world rather than just dictate where we’re going to go after life.”

Still, Ou tries not to focus on sinning, which she describes as “doing bad things,” and instead simply be a good person. She says the “crowd you hang out with” can have a strong influence on the way one looks at sins, as potential bad influences can result in an individual frequently questioning if they’re committing a sin.

Because Ou has carried these values throughout her life, she says that they have become “the foundation of her current values.” Now, the teachings from her faith have led to her being optimistic about the future.

“I think a lot of religions are the same way where it gives you hope that there is something greater than life,” Ou said. “And being a Christian gives you purpose, which impacts someone’s life a lot. When you have a sense of purpose in your life, then you feel motivated to just stay alive and keep doing things to make other people happy.”

Krish Lariya

Freshman Krish Lariya boils “karma” down to “if you do good things, you’ll be rewarded with good things.” Because one of the key ideas of Hinduism is reincarnation, karma plays a large role in Lariya’s life — since these “good things” determine the luck in one’s current life and future ones, he views these lives as “second chances.”

In his daily life, Lariya tries to obtain good karma by respecting his elders — an important value of Hinduism — and doing community service. He also practices thinking before he speaks because he wants to be “respectful to everyone” and avoid pushing “anything too far” while making jokes. He says that karma makes him consider the “difference between right and wrong, and which side [he] should be on.”

He credits this critical thinking to his family, who taught him these values through discussions starting in elementary school. His parents would remind him of karma when he shared his mistakes, and as Lariya grew up, he began believing in karma himself. For example, he would attribute a simple action of stubbing his toe to be a result of procrastinating on his homework or upsetting his parents.

“If I do something good, I feel like I would be rewarded with a good future [with] enjoyment, and even [just] enough money to survive,” Lariya said. “Karma [is] a big thing, and it ties back to everything in Hinduism — a lot of things are based off of karma, [and] I think the future relates to karma.”