Lloyd Holmes: the new president of De Anza College

Holmes shares his experiences with race, education and giving back

October 26, 2020

The color of his skin hadn’t been an issue for current De Anza College President Lloyd Holmes until one evening in 1990 while walking to his dorm. It was almost the weekend, and he had just gotten his mail from the University of Mississippi post office when a group of four white college boys drove by in their green Jeep. They were waving a Confederate flag, screaming, “[N-word], go home.”

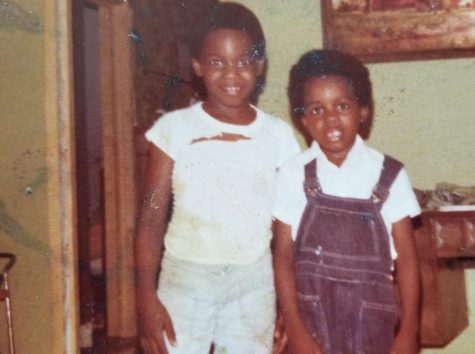

Holmes’ dad died when he was nine months old. Unemployed and with two kids, his mother took her family on welfare. Until Holmes was six, his family didn’t have a bathroom. Until he was 11, they didn’t have store-bought clothes. Until his sixth grade, they ate peas and cornbread for “days on end”. When Holmes joined his school band, he was given a loaner trombone because he couldn’t afford an instrument.

Nonetheless, his mother knew the importance of education. Holmes got nearly-straight As in high school, graduating third in his class. was part of his school’s volunteer club and served as vice president in student government. Beyond academics, he “opened his mind” to the arts and music, piano-playing being central in his youth.

“We had an old piano in our house and my mom was gung ho about one of us taking lessons,” Holmes said. “My brother and I got tired of her asking so [we] made a deal with each other that if I took piano lessons, he would clean the house when it needed cleaning … When I was 14, I started playing for a church in Mississippi.”

Holmes spent four days a week practicing the piano, and had played for three other churches by the time he graduated from high school. Holmes recounts how he never skipped class or even spent time with his classmates on the weekends — he simply didn’t have the time.

“My mom always thought education was the key that would unlock so many doors,” Holmes said. “She saw education as the key to moving beyond the situation we were in. So the idea of bringing a C home to my mom, that was the worst thing [I] could possibly do … I think she always felt that if she had had more education, then we probably would not have grown up in the situation we did.”

In his senior year, Holmes received multiple scholarship offers, two of them to Mississippi Valley State and Alcorn State, both historically Black universities. However, since none of them offered his preferred major, Architecture, Holmes attended his local community college instead. A year later, he switched his major to Accounting and transferred to the University of Mississippi, or “Ole Miss,” with his community college roommate Earnest Stephens, whom he eventually became close friends with.

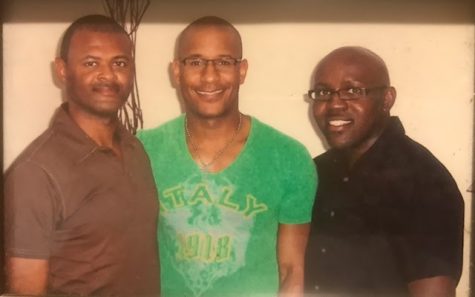

“It was nice to be around someone who seemed like they were following the same path that you were trying to be on, which was [to] obtain your degree,” Stephens said. “[We] didn’t necessarily know where that path was leading, but we knew that education was the pathway to get [us] to where [we] were going.”

At Ole Miss, Stephens and Holmes both participated in the same choir and formed a close circle of friends. They became roommates again at Mississippi. Soon after moving, they attended a home football game against Memphis State; lights had been recently installed, allowing games to happen in the late evening.

“I absolutely loved college football,” Holmes said. “[Mississippi’s] football stadium seats probably 65,000 people. But when I went there as a junior, I didn’t realize that the Black students didn’t sit in the student section at the 30 yard line. They sat [near] the end zone.”

According to Stephens, there were less than 1,000 Black students on campus at the time. At every home game, the school flew the Confederate flag. As the band played the Confederate song “Dixie”, the student section chanted, “the South will rise again”.

“I remember getting kind of damp and then something whizzing by my ear,” Stephens said. “Someone had thrown a beer bottle. I remember [Holmes and I] walking after the game and we were saying, ‘We are not coming back to another game.’ I didn’t go back to another game for several years. I don’t think [Holmes] ever went to another game.”

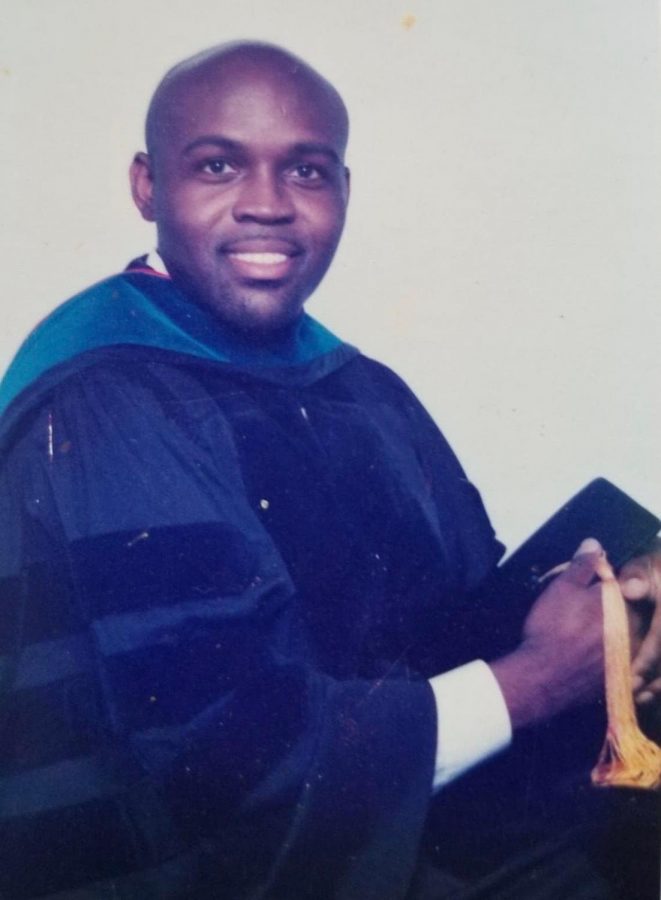

Holmes didn’t leave the University of Mississippi after that incident. Nor did he leave after being called a [N-word] when walking down the street from the post office. Not only did he complete his undergraduate degree in Accounting there, but he also earned a Masters of Higher Education and a Ph.D. in Educational Leadership from Ole Miss.

“I realized this is just as much my home as it is those white guys that screamed those derogatory remarks at me, and so I decided at that time that [the] University of Mississippi was my home,” Holmes said. “It was those experiences that had such an impact on me because I had never remembered being referred to as a N-word.”

Stephens recalls Holmes undergoing an academic transformation when he switched to higher education and went to graduate school. Later, when Stephen himself was sitting in his dorm room one night during his senior year, unsure of what to pursue, Holmes urged him to apply for the same program at Ole Miss that he applied to a year before. Stephen applied and got accepted.

“That one conversation changed my life,” Stephens said. “I had no idea that graduate school was even an option for me until that point … From there I caught the bug. I went on and applied to get into a PhD program. I got my PhD. But it all started with [Holmes] and that conversation we had one night sitting around in his dorm.”

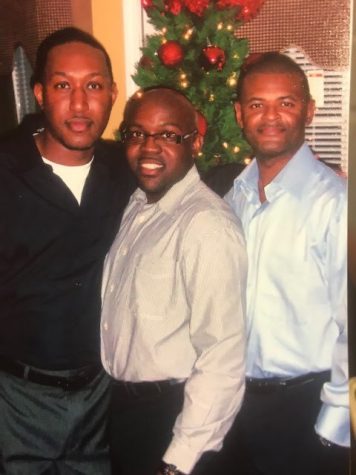

After finishing his doctorate in Educational Leadership, Holmes worked as the Dean of Students at Coastal Carolina University and North Shore Community College, and later became the Vice President of Student Services at Monroe Community College. There, he led a program called the TRIB Student Support Services to address student poverty and financial insecurity.

After collecting data around the student population and depth of the problems, Holmes created a team, including Associate Vice President of Student Services John Delate. Together, they met with community colleges across the nation, raised funds from the school’s foundation and built a program that was nationally recognized for student support.

“[Holmes’s] motto was, ‘If we give them a fish, they’re going to eat for a day. If we teach them to fish, they’re going to eat for a lifetime on their own,’” Delate said. “It’s a great combination because he understood the plight, he had been there, but he also understood sympathy wasn’t going to help someone get to the next level.”

Holmes worked at Monroe for six years before getting appointed as president of De Anza Community College in Cupertino. During his time at De Anza, Holmes hopes to make the staff more diverse, tackle issues of student homelessness and food insecurity and build a community of respect, according to his candidate interview. In many ways, he will be tackling the issues he personally faced throughout his life.

“His story was always about empowerment, success and confidence,” Delate said. “It wasn’t about victimhood. It wasn’t chastisement, it was encouragement, empowerment and really a message of hope.”

Holmes emphasizes the importance of education and “expanding your brain”. He uses the analogy of a mud puddle, explaining that when throwing rocks into the puddle, the ripples allow you to slowly see more depth. Holmes says education does the same.

“[As] a poor guy who grew up in Mississippi, who ate peas and cornbread for days on end, I could never have told anybody, you couldn’t have even told my mom, that I would be a college president at one of the top community colleges in the country,” Lloyd said. “Even when I was walking down that sidewalk at the University of Mississippi being called the N-word, you could not have [told] me at that time that I would be given the opportunity to serve [as president at] such a great institution. You don’t know what the future holds. So for everything you can soak in, do it now.”