The illness of sickly beautification: romanticizing mental health

April 27, 2019

Romanticization is a complexity — it unveils the allure in beliefs that are less than ideal. Series of “cute and psycho” posts on Tumblr and flurries of quotes bunched under the “pretty and dying” Pinterest folder — the glamorization of mental disorders amidst our social networking culture isn’t a taboo. It’s simply a trend to beautify the reality of mental illnesses.

Through concentrated efforts, awareness and events like the World Mental Health Day on Oct. 10, health organizations have established that mental health isn’t a lighthearted topic to tiptoe around. However, with social media platforms perpetuating the beautification of mental disorders, our efforts to de-stigmatize mental illnesses have been reversed. Now, having these illnesses allows for an environment in conformity, because it’s “trendy.” It’s “trendy” to be diagnosed with depression, anxiety, OCD — the list goes on.

“Suicidal people … are just angels that want to go home.”

“I have more scars than friends.”

“I’m jealous of people with enough self control to be anorexic.”

This “trendiness” stems from the preconceived notion that we want to divulge from normality, because we want to be special — and mental illnesses cast us away from regularity. Nowadays, mental health is fathomed as an accessory — a quirky personality trait.

https://www.canva.com/design/DADYXAyGn0E/view

Suddenly, people who are sad for a few hours dub themselves as depressed. Skipping a lunch meal validates the title of anorexia. Being stressed indicates that anxiety is on the prowl.

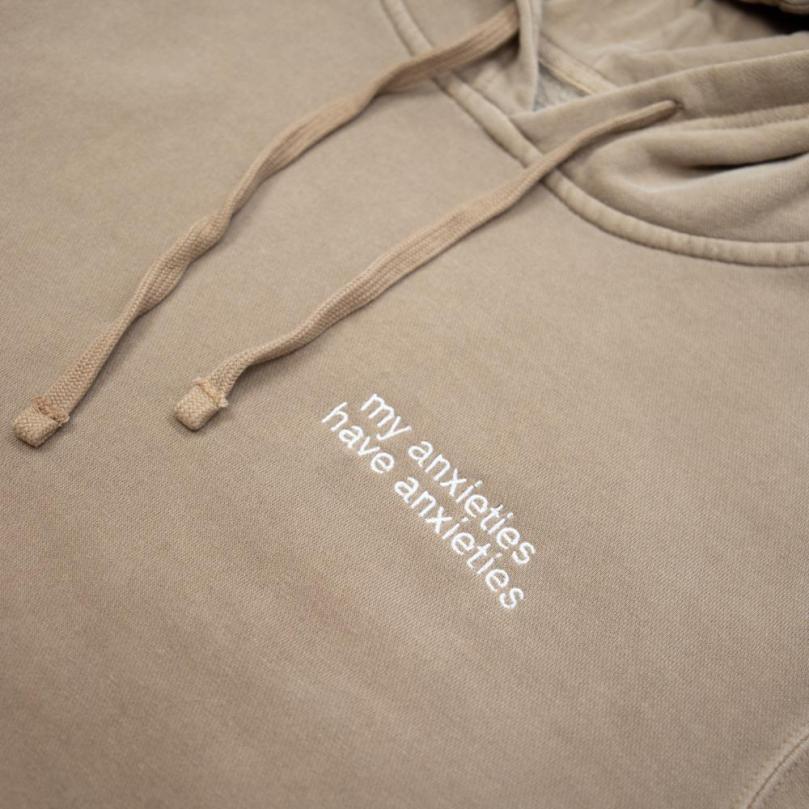

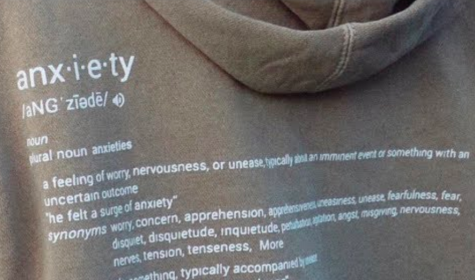

Social media influencers exploit the glamorization of mental illnesses for monetary purposes, bringing such beautification into marketing. American Youtuber Corinna Kopf’s controversial merchandise line is a case study of the romanticization of anxiety, branding anxiety as an aesthetic decoration.

Promoting merchandise with the words “my anxieties have anxieties” stitched on the fabric, Kopf argues on her Twitter that “if you think I’m making a huge profit off it, I’m really not.”

This is a sickly depiction of anxiety beautification; anxiety is neither beautiful nor is it captivating — anxiety is a weight. Though buyers claim that wearing merchandise like such is a coping mechanism, branding anxiety as a fashion statement fathoms it as desirable, when the reality is that it’s not aesthetic or stylish. Desensitized with flowery exhibitions, marketing anxiety downplays the severity of the issue.

Anxiety is not a selling point — the fact that Kopf is glamorizing anxiety as a fashion trend is disgustingly unsettling. If you so happened to be diagnosed with anxiety, in what way would you ever want to be branded with it? Walking around in a pullover stitched with words like “OCD” and “MENTAL” in the eyes of people who are mentally ill flaunts the disorder.

People are enamored through the “charming” facets of posts promoting mental illnesses as an art form. The magnitude of being depressed is erased when Pinterest and Tumblr spread the artistry of being “broken.” Creativity doesn’t amount to how “damaged” a person is — such romanticization plucks at the stigmatized flaws of mental health and presents it as an art canvas.

There is a fine line between awareness and romanticization; while glamorizing mental illnesses is a light attempt to spread awareness in communities, its half-hearted intentions are often executed horribly. It’s true that adolescents are exposed to this due to social networking. However, there are many other efficient and less problematic ways to spread the word.

Instead, we as a community need to steer ourselves in the right direction by utilizing social platforms as a support system. Influencers with a platform online need to promote awareness through fundraisers and rooted conversations with their fanbases, not just by slapping the word “anxiety” on a hoodie to sell.

Self mutilation doesn’t make a person more captivating and depression doesn’t make a person more enticing — there is no charm to being mentally ill.

In the end, pain hurts. And pain is not pretty, no matter how much social networking adorns it.