The first time I passed to my mother was in the passenger seat on the way home from a formal event, wearing a thin blouse, agreeable earrings and makeup that made my eyelashes crusty. I felt distant, but parental conversation itched to fill empty space, so conversation flowed from one topic to the next until we landed back on ourselves. She told me that another parent had asked me whether I was her son or her daughter.

I didn’t respond. The comment caught me off guard since she usually doesn’t pay much attention to my social life or hobbies; why would gender be any different? Still, that ambiguity was alluring—who was I? Who could I be if I didn’t have to be a woman?

I had first tossed around the idea of being nonbinary in the middle of my freshman year, and, through gradual introspection, became comfortable with the concept. But it was one thing to reconcile that identity with myself, and another to start expressing it to others.

That particular moment was ironic, given that it was the one day I wasn’t actively trying to look masculine, or even gender-neutral. But it was true that I had been making the effort in general, swapping out baby tees for loose shirts that made me look a little like my father. The comment marked the beginning of my mother’s small but prickly observations that I avoided the dresses she chose, that my hair was too short to be pretty, that I could be elevated to the beauty of a K-pop idol if only I tried.

It would be an easier way out. I could follow her suggestions. I could pass strictly as female.

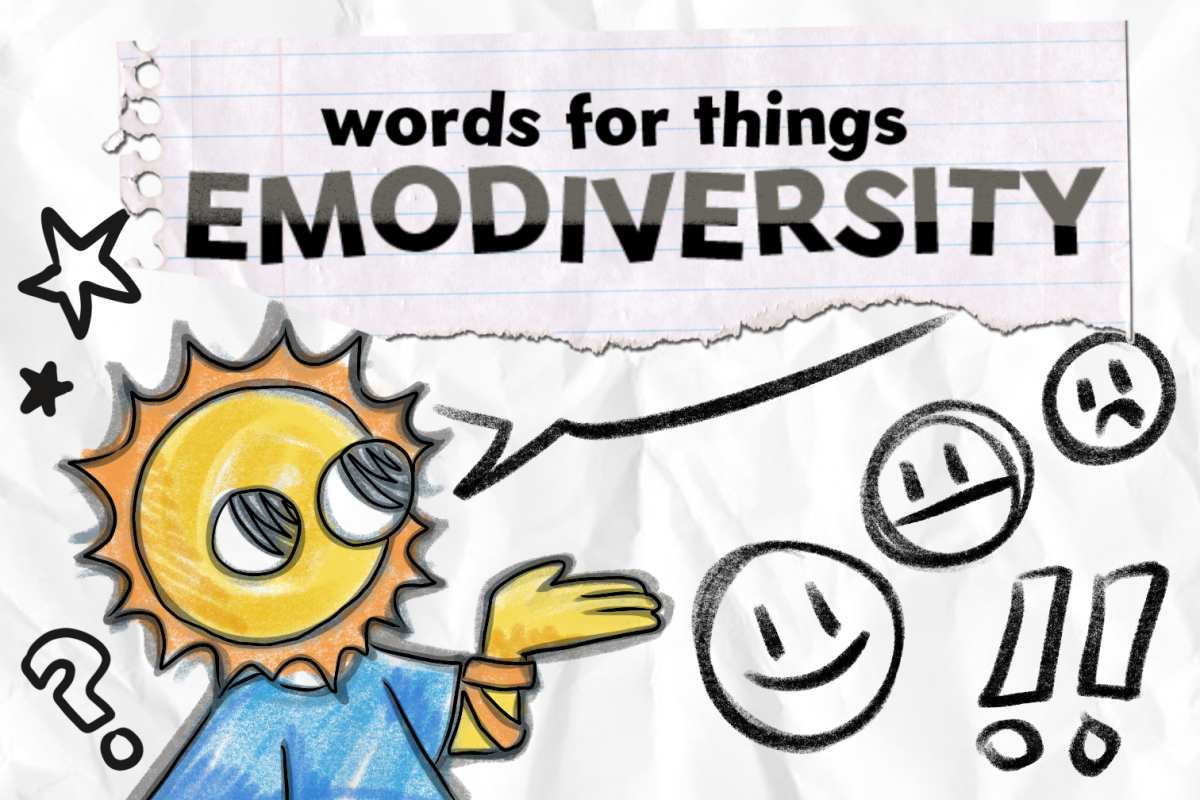

Appearance is central to the idea of queer passing, which is when a transgender person meets the societal standard for “appearing cis.” But beyond the standard definition, passing is a concept that can apply to any identity. Everything we are or aren’t—a certain ethnicity, a certain personality type, a certain standard for an MVHS student—will always be refracted through others’ standards. Existing is a lifelong tug between authenticity and acceptance.

I’m not the first one to point that out. But what queer passing has taught me is that acceptance is always a little bit of a compromise, rounding out edges to fit a little more neatly into others’ definitions.

The idea of queer passing itself is flawed; it has been criticized for how it reinforces the gender binary, and rightfully so. At the same time, treating it like a choice ignores the many trans people living in hostile communities who have to pass for the sake of their safety.

So I don’t mean to make analogies between survival and my privilege of living in an accepting area. In an ideal world, the concept of passing shouldn’t exist at all, nor should it be a nonconforming person’s responsibility. But as I get used to my mother’s increasingly aggressive side-eyes, I’ve learned to confront her questions more head-on instead of accepting my place as the accused.

I talk and dress the way I do, not because it fits someone else’s idea of what I should be, but because it feels natural to me.

Instead of continuing to assume that my mother will always be someone who “doesn’t get it,” I’ve been trying to explain things more simply. I don’t like dresses—they feel uncomfortable to me. Hair doesn’t define anyone, regardless of gender. And K-pop was never really my style. She still might not like my reasons, but they’re concrete. They bring me one step closer to painting a fuller picture of myself.

Destigmatizing identity starts with a basic, uncomfortable dialogue that explains each side. But that talk can go a long way in setting boundaries for how people are perceived and who they really are. We’re more than who we seem at a passing glance. Our conversations can reflect that.