For the purpose of maintaining their anonymity in this story, we will refer to two Stanford University affiliates as Stanford A and Stanford B, respectively. The third reporter of this story is anonymous due to safety concerns.

Students at Columbia University set up an encampment in protest of the Israel-Hamas war on April 17, the same day that Columbia University president Nemat Shafik testified at a Congressional Committee Hearing in Washington, D.C. about antisemitism at Columbia. Shafik called police to end the encampment on April 18, resulting in the arrests of over 100 students for trespassing — a decision that sparked national media attention and a flare of similar encampments on college campuses across the country.

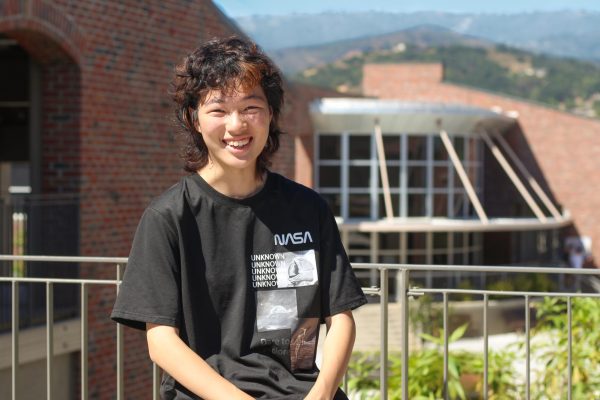

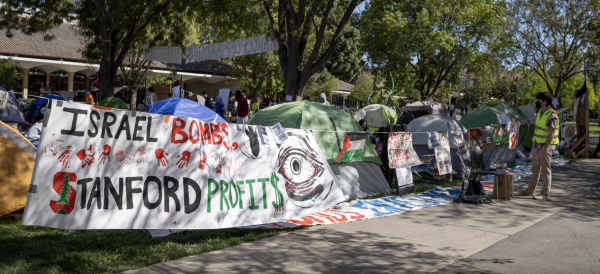

Stanford University restarted its encampment on April 25 in the White Plaza, where Stanford students had previously organized a 120-day sit-in protest against the Israel-Hamas war on Oct. 20, 2023. Stanford A, an affiliate of Stanford University and an organizer for the protests, emphasizes divestment, a common demand in campus protests, as the end goal of the encampment. Stanford students are demanding that the university cut its ties to companies funding Israel, such as Lockheed Martin and HP.

“There was also a sit-in for apartheid in South Africa, and that one was successful in making Stanford divest from the apartheid,” Stanford B, another Stanford affiliate, said. “Seeing that, we were like, ‘Let’s give it a try.’ In the beginning, it was just like five people, and slowly more students came in and were asking questions and wanted to see what it was about. So then we started to grow as a community, and it quickly became what mobilized students into joining the new protest.”

Students protesting at Stanford see the institution as complicit in genocide due to its investments and ties to Israeli-affiliated companies. They opted to enclose their encampment using rope and posters with pro-Palestian messages to create a People’s University for Palestine — a space where students can study and socialize separately from Stanford. According to the Gaza Health Ministry, the death toll in Gaza has exceeded 35,000 as of May 22, over 15,000 of which are women and children. Tracking and announcing updates to these statistics are central to check-ins led by students at the Stanford encampment. Each day’s schedule also devotes time to sharing stories, watching documentaries and engaging in discussions.

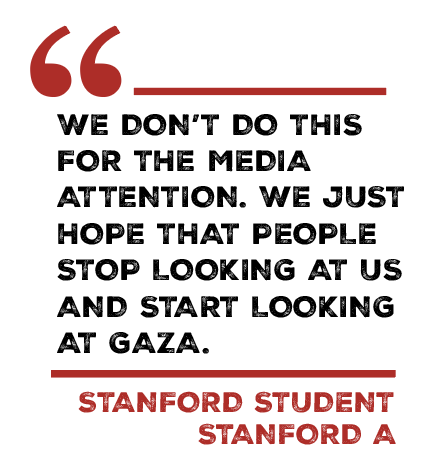

“We don’t do this for the media attention,” Stanford A said. “We never have, and we never will. We just hope that people stop looking at us and start looking at Gaza. It is very intentional that most of the news outlets that you see now are covering universities and not covering the ongoing genocide. What we try to make sure of is that we center ourselves in Gaza every single time we do this, every single day of this conversation.”

MVHS ‘23 alum and freshman at the University of Washington Maya Mizrahi believes increased media scrutiny has nevertheless hindered conversation around the conflict. Mizrahi finds that many of her peers have become less open-minded in their stances on the war, which has impacted her relationships as a Jewish student who identifies with Israel and has Israeli family members.

“I’ve had friends of many years, who I consider to be close friends, unfollow me without a word, or just stop speaking to me,” Mizrahi said. “It’s very frustrating because I feel that I’m open-minded enough to sit down and have a conversation and have respect for the other person regardless of how different their views are from mine. It’s sad that we can’t all have that mindset and that respect for each other.”

Mizrahi recalls seeing students in UW’s encampment being harassed for wearing the Star of David. In another incident, protesters vandalized UW’s Husky Union Building by writing pro-Palestinian slogans on the walls and damaging student artwork on display, including drawing an inverted black triangle, a Nazi concentration camp badge, on a Jewish student’s artwork.

“Demonstrating and using your First Amendment right to free speech is not inherently antisemitic,” Mizrahi said. “And that’s not exactly what I have a problem with. The issue is when you see someone visibly Jewish and automatically make it about the conflict. The issue is screaming at Jewish students that they should go back to where they came from — that is absolutely antisemitic.”

However, both Stanford A and Stanford B describe the encampment at Stanford as a welcoming space for everyone, as they say it condemns antisemitism, Islamophobia and all other forms of discrimination and hate. Alongside Palestinian folk dance performances and memorials for Palestinian casualties, student organizers have also hosted cultural events such as a Passover Seder, a Jewish ritual feast. Stanford B views the general label of antisemitism on the student protests as a tool used to shut down the students’ actions and to deflect from the conflict in Gaza.

“At the end of the day, it is not antisemitic to ask for a free Palestine, to ask to stop killing babies and to stop killing people in general,” Stanford B said. “We have people coming in every day trying to take pictures and doxxing students and trying to pick up the names of students so they can get them in trouble. I personally have been called a terrorist for wearing the headscarf and for being Muslim. We have had all sorts of harassment from Zionists just for fighting for this movement when we have done nothing to them.”

Lawmakers and university officials across the nation have struggled to differentiate political activism and antisemitism. Student protesters, including Stanford A and Stanford B, distinguish antisemitism, prejudice against Jewish people, from anti-Zionism — opposition to Israel’s national ideology, which lays claim to Palestine as Jewish people’s ancestral homeland. Others, such as the World Jewish Congress, argue that anti-Zionism forces Jewish people to denounce an integral part of their ethnic identity. They say that criticisms of Israel often mask antisemitic stereotypes of Jewish individuals.

Though protests at both Stanford and UW have not escalated to the point where students have trouble going to class, Mizrahi says the encampment and rallies leave many Jewish students, including herself, afraid that violence will break out on campus targeting them. She points to chants for “Intifada,” an Arabic word for uprising and rebellions generally used to refer to Palestinian uprisings against Israeli control, and used by protesters to promote activism supporting the Palestinian resistance. Historically, both the First and Second Intifadas in Israel and Palestinian territories were periods of violent protests with significant casualties.

“I have known people to be affected by various Intifadas, and to call for an Intifada to happen in the U.S. and on a college campus is very scary,” Mizrahi said. “All of my classes are near where the encampment is currently. Some days it is scary to walk through it, and I have been yelled at and harassed when I do display my Jewish identity.”

In a statement released May 7, Stanford officials said that though the First Amendment protects the majority of speech, the university will take action regarding constitutionally unprotected speech or behavior that violates others’ rights. Officials also condemned the encampment, citing not only violations of the university’s policies on overnight camping and appropriate use of White Plaza, but also stating that by design, the encampment does not encourage discussion — it only shuts out people who disagree with the protesters.

Stanford officials also encouraged students to attend discussions convened by the university rather than protesting and engaging with protesters, which have escalated to disproportionate retaliatory force at other college campuses. As of May 7, Stanford is in the process of identifying students participating in the encampment to be disciplined. Regardless, Stanford A and Stanford B say that protesters will continue to fight until their demands are met.

“We’re anti-administration,” Stanford A said. “We always have been. We always will be. We hate that this has been co-opted as a narrative of free speech because that’s not what this is. We’re not saying that you should support us because we have a right to do this even if you disagree with us. We are saying that you should support us because we are doing the right thing.”

On May 17, UW officials and representatives from the encampment on campus reached an agreement for the encampment to disband. Mizrahi has been working with the UW chapter of Students Supporting Israel, an international Zionist student organization, to set up tables to engage other students in discussion on the conflict. She says they aren’t trying to counterprotest, but protesters have nevertheless approached them to yell pro-Palestinian slogans. She hopes to eventually foster an environment where students who are involved in either side of the conflict and who are hurting can talk to each other.

“I don’t believe that everyone’s opinion can be reduced to a slogan or a chant,” Mizrahi said. “And I would really like to find out what they actually think and then go from there. What we’re seeing right now is a lot of outside actors coming in and dividing the conversation even more. It’s making it harder for us, the people who are involved, to have conversations with each other. So ultimately, my goal is to have open communication — to even start talking about what might be a good solution. But I just think we’re very far away from that right now, unfortunately.”