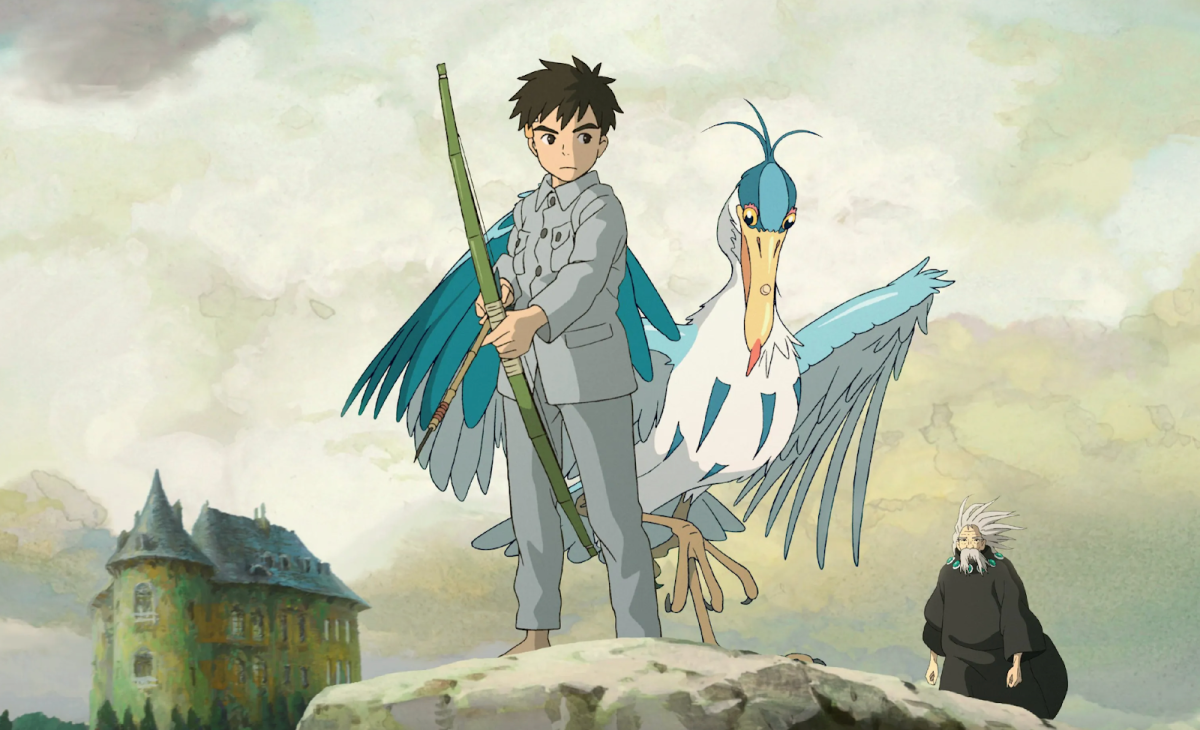

In an explosion of vibrant surrealism, anthropomorphic animals and bird poop, “The Boy and the Heron” took flight in theaters on Dec. 8, marking Studio Ghibli’s first film since “The Wind Rises” in 2013. Japanese filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki teleports audiences back into the nostalgic realm of hand-drawn animation through the eyes of Mahito, a young boy struggling to come to terms with his mother’s death. As Mahito struggles to acclimate to his new life with a new mother, he finds a portal within a crumbling tower that reveals a breathtaking alternate dimension filled with strange and familiar beings — one he must navigate alongside the belligerent Grey Heron to either save the fantastical world or reunite his new family.

From start to finish, Miyazaki’s eccentric imagination immerses viewers in Mahito’s supernatural coming-of-age story. Details that verge on outlandishness, from meat-eating parakeet soldiers to boats rowed by ghosts, intertwine with a multitude of themes to create a fantasy world as weird and entertaining as it is complex. The narrative finds depth in the interplay between Mahito’s grief and his lighthearted moments of childlike wonder, drawing inspiration from Miyazaki’s own life to weave together a masterful exploration of family, loss, life and death.

The art style takes a unique route compared to modern movies, with every scene being hand-drawn by artists and evoking feelings of childhood nostalgia. Studio Ghibli’s art style is renowned for its beauty and creativity, with details in each scene revealing the hours of dedication that go into the surrealism within the movie. Lingering frames add to the surrealism of “The Boy and the Heron,” as Miyazaki creates many moments for the audience to pause and admire each detail within a scene.

“The Boy and the Heron” also takes sound design to the next level with its poignant score. Caterwauling violins haunt the hellfire of Mahito’s flashbacks and gentle piano softens the quieter moments, while stunning visuals interweave with mesmerizing foley to instill life in every detail. Although both the Japanese and English voice actors infuse authentic personality into their hodgepodge of roles — with Robert Pattison pulling off an admirably unrecognizable performance as the Grey Heron — some of the most impactful scenes are ultimately those with the fewest words spoken.

Miyazaki proves his impressive attention to detail in the movie not only through visuals and audio, but also metaphorically. For instance, while fire and water are opposite elements with different implications, in “The Boy and the Heron,” Mahito faces physical obstacles on his journey relating to the destructive power of water while he embraces relationships and is often saved from death when surrounded by the warmth of fire. As a result, Miyazaki is able to subvert viewers’ expectations and manipulate connotations within the movie, pushing the audience to look further and challenge expected tropes, which adds an admirable amount of depth.

A slew of references to other Studio Ghibli films will delight long-time fans in “The Boy and the Heron.” Before its premiere in Japan, Miyazaki cited “The Boy and the Heron” as his final Studio Ghibli movie, and as a result, the movie honors Miyazaki’s past creations through parallels with movies he has directed in the past. For example, Miyazaki’s past creation “Spirited Away,” premiered in 2001, captures main character Chihiro navigating a world of fantasy and monsters. As young children adjusting to a new life, Chihiro and Mahito share similar characteristics, and Miyazaki acknowledges this by including scenes of each character close up, with widened eyes. These two scenes are visually stark in their alikeness, and Miyazaki draws many more parallels throughout the movie, further enhancing the experience for seasoned Studio Ghibli lovers.

While “The Boy and the Heron” unmistakably excels in visual beauty, it suffers from erratic pacing and a plot riddled with nonsensicalities. A long-winded first act sends the film plunging towards a hasty fever dream of a climax, in which Mahito’s struggles with insurmountable grief come to an abrupt close. As the otherworldly and real bleed together, Miyazaki’s chaotic worldbuilding and adamant refusal to spoon-feed viewers makes for a plot that is as overwhelming as it is thought-provoking, demanding a rewatch or an hour of processing in place of a straightforward, linear resolution.

Despite his bewildering storytelling, Miyazaki’s artistry and ambition makes for a heartfelt film, rooted in the unique animation style and unapologetic bizarreness of Studio Ghibli’s best. While this movie was said to be the last of Miyazaki’s career, Miyazaki has since returned to Studio Ghibli, ready to pitch ideas for new movies. Ultimately, “The Boy and the Heron” revives a 10 year hiatus-filled chapter of movies that are essential not only to Miyazaki’s legacy but the evolution of art, leaving viewers excited for what’s next.

4/5

Correction: Jan. 18, 11:03 A.M. A spelling error in Hayao Miyazaki’s name was corrected.