The student source in this story is anonymous due to privacy concerns and will be referred to as Student A.

As their curiosity built up, Student A couldn’t help but ask more questions regarding sexual health during their annual check-up with their doctor in 7th grade. The doctor answered their questions on topics that helped them understand their own sexuality without judgment, which gave them the courage to explore more by themselves. They started feeling more confident about themselves through learning more. However, they acknowledge that a lot of the other people they talked to didn’t share their curiosity, and often felt uncomfortable reaching out to others about topics surrounding sex education. The Responsible Sex Ed Institute states that people observe a stigma around sex education that often inhibits their curiosity and prevents them from asking more questions.

A school district is able to select which curriculum and resources, such as textbooks and worksheets, it will use to educate its students. California state law describes comprehensive sexual health education as education regarding human development and sexuality, including education on pregnancy, contraception, and sexually transmitted infections (EC § 51931[b]). Currently, California AB 329 requires students to receive comprehensive sexual health education, including learning about HIV prevention, once in middle school and once in high school.

At MVHS, sex education is currently taught during the second semester of freshman Biology across three and a half weeks. During the 10 to 13 hours of class time dedicated to sex ed, teachers aim to teach about topics such as human development, relationships, personal skills, sexual behavior, sexual health and society and culture.

Despite this, some argue that the sexual education currently provided to students simply isn’t enough. In a survey of 1,500 Americans, aged 18 to 44, 90% of respondents said their sex education had not prepared them for real-world sexual experiences. Many felt that they didn’t know enough about topics such as sexual hormones and fertility cycles, which could lead to problems when people are unable to recognize certain health risks such as sexually transmitted infections and issues that affect women, such as endometrial cancer and anemia. In the MVHS community, 63% of students stated that they felt MVHS’ sex education was only somewhat helpful, while 22% stated that it wasn’t helpful at all.

Junior Nishant Chatterjee notes that although the sexual health unit in 9th grade went in-depth in some areas, it lacked in other areas that he thought were important for his well-being and future preparation for sexual encounters and health risks.

“If someone asked me, I feel like I wouldn’t know or be able to tell them about a lot of things related to sex ed,” Chatterjee said. “I feel like the unit definitely went really deep into communication and consent, but when it came to things like sexual hormones and body parts, I don’t think they taught these things enough, and I don’t think I’d be prepared for a future sexual encounter.”

Freshman Biology teacher Lora Lerner believes that three weeks isn’t enough time to provide comprehensive sex ed, especially since every topic offers complexity and is important to teach. To combat this issue, she aims to maximize the time she has by prioritizing certain topics that are hard for students to navigate on their own, such as dealing with the hard parts of relationships, asking for consent and how to talk to people about getting tested for STIs. She especially wants to touch on topics that students are not likely to talk to their parents about. Chatterjee and Student A both voiced the idea that while the current sex education in school is still important, it does not provide a thorough understanding of all essential aspects.

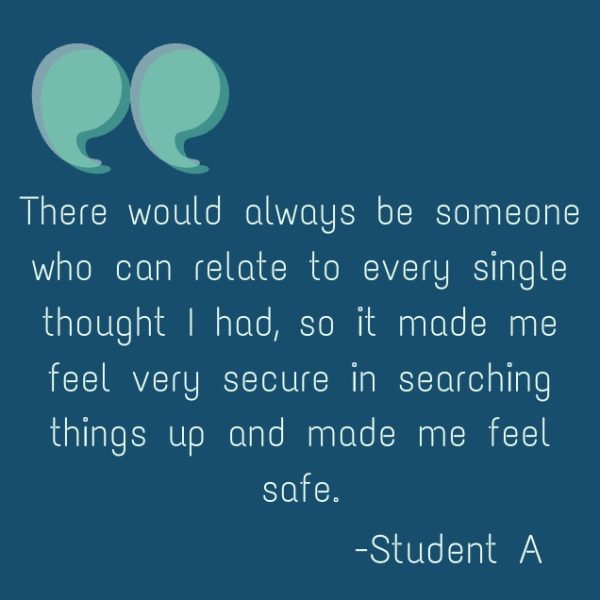

Student A explains that although the emphasis on communication was helpful, they still felt like the sex education unit did not cover everything they needed to know. While they could talk to their older brother about more general questions regarding sex education, they often felt ashamed and embarrassed, which left them feeling unsafe to talk about anything too graphic or ask specific questions. As a result, they turned to online resources for additional information.

“The Internet was the biggest source of information and I felt some sort of reliance on it, because I knew that if I did have a question, it could be answered online,” Student A said. “There would always be someone who can relate to every single thought I had, so it made me feel very secure in searching things up and made me feel safe.”

Lerner emphasizes that it is important to be particular about the online resources you use and not just refer to a singular resource. Instead, she recommends that students lateral read, or compare a source with other sources to verify its credibility, to reach a comprehensive idea on the topic they are researching.

“If you can use multiple reliable sources, that’s a good strategy for anything because there’s just a lot of junk out there,” Lerner said. “You have to be careful that you don’t just reinforce the same junk with related websites. You have to go way out here somewhere and figure out or maybe ask some people that have some expertise so that you’re getting different points of view and also recognizing when something is factual and has an answer because some things are factual and they have an answer.”

Chatterjee has confided in his parents to answer questions he had regarding sex ed, as he trusted his parents and believed they could provide accurate information. While he did try relying on the internet for information, he didn’t find it helpful because he found sites with content that made him uncomfortable and were not what he was looking for. He concluded that he preferred communicating with a real person to get the answers he wanted.

“It’s important to understand your parents and evaluate whether or not they are a good source of information,” Chatterjee said. “If you trust them and they seem like they know what they’re talking about, then it is good to ask them about it because they are very close to you. However, if you aren’t close to your parents or don’t trust them for whatever reason, it might be better to seek a more reliable source.”

Lerner agrees that parents are a vital resource, as they are the most powerful influence that helps you figure out your identity and values. However, as Chatterjee acknowledges, parents might not be knowledgeable in some areas, in which the student would have to look to other places to get their information. In that case, the school still serves as a place students can rely on as there are numerous people on-campus students can talk to.

Lerner believes that when it comes to sex ed, it’s not hard for her to recommend sources such as Planned Parenthood, Scarlet Teen and parental advice, nor is it hard for her to advise students to steer away from non-evidence-based sources such as porn and social media. But her main advice is for students to start thinking for themselves and determining where they will go for information in college and beyond. She feels students should have a sense of internal confidence and be able to think critically by treating sex ed the same way as any other health issue.

“I hope people will keep learning the rest of their lives, because you’ll continue to encounter different situations and challenges as you try to date, find a partner, maybe have kids or have problems with your parents,” Lerner said. “The problems are endless, but I have ideas about my own internal strengths and the times I need to get help, as well as where I can get that. That’s what’s going to carry you through, it’s recognizing that you’re not alone.”