Playing the name game

Examining how names and pronunciation play a role in the classroom

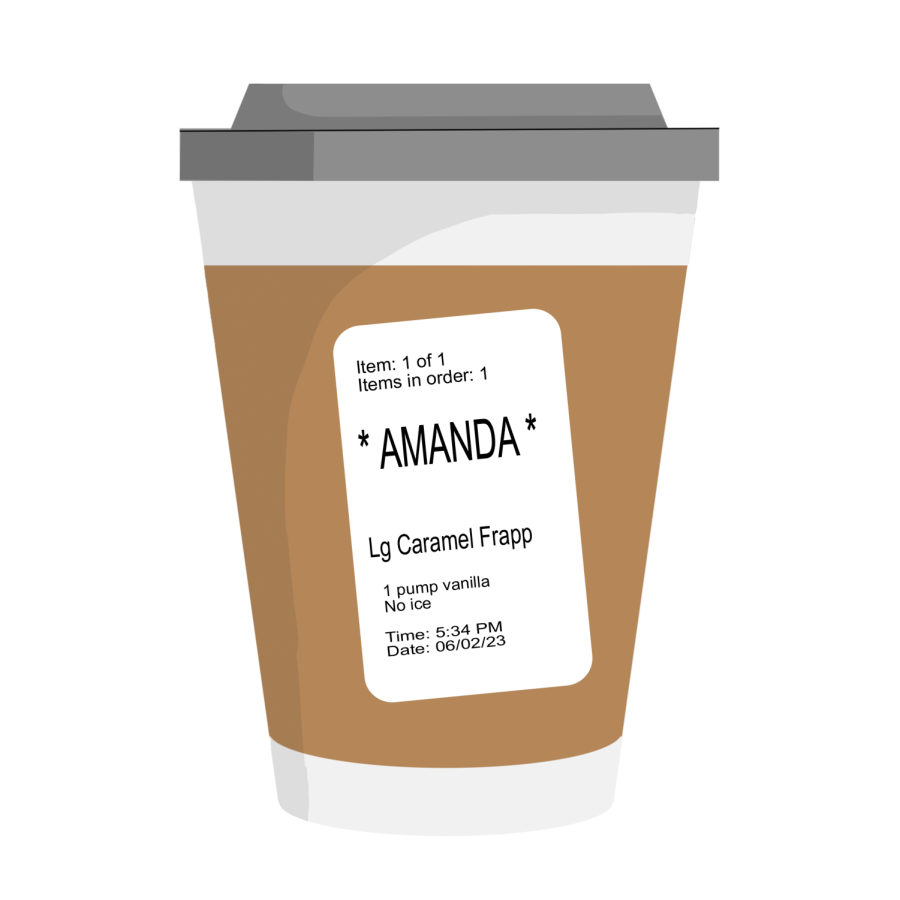

Senior Rokiya Elhak changes her name to “Amanda” when ordering at coffee shops

June 4, 2023

As senior Rokiya Elhak approached the front of the line at Starbucks, she contemplated what name she should use. Afraid of having to correct the barista who was taking her order, she chose the name “Amanda” instead of her real name. Elhak finds that using a different name is easier because she “doesn’t have to worry about [correcting someone],” an interaction that she finds awkward.

With the prominence of similar name-related struggles in our racially diverse community, the MVHS administration implemented NameCoach in Schoology at the beginning of the 2021-2022 school year. With NameCoach, students could submit recordings and phonetic spellings of their names for teachers to learn how to pronounce them correctly.

For MVHS Alum ‘22 Pradyuman Vijayakumar, NameCoach was a helpful tool because it prevented him from having to constantly correct his teachers’ pronunciation of his name, especially during the pandemic.

“Online, it’s different because [teachers] just read the name on the screen, it’s like you’re walking around with a nametag, [so] there’s more chance of mispronouncing [names],” Vijayakumar said.

However, NameCoach itself had certain drawbacks that prevented it from being used in subsequent years. According to English teacher Monica Jariwala, since a student’s NameCoach submission did not sync across multiple Schoology courses, the application itself was discontinued as it proved inefficient and teachers were left to create their own systems for introductions. Senior Hernan Maldonado also believed that NameCoach wasn’t being used in an effective way during remote instruction because different classes used it in different ways.

“I think everybody just forgot about it, including me,” Maldonado said. “I don’t think NameCoach was successful at all [in some classes] because if it was, I wouldn’t have [had] to correct my teachers.”

As an alternative, teachers were encouraged to use bonding activities to help students teach their names to their teachers as well as other peers. Elhak recalls how a name game, where the students verbally said each person’s name along with a gesture, improved how people pronounced her name and also helped students remember each others’ names.

“[Our class] did a name video on Flipgrid, and I know a lot of other teachers did something like that on Schoology or Flipgrid,” Jariwala said. “I really appreciated the idea that we made so much of a focus on names and pronouns.”

In contrast, Maldonado believes that certain games are better than others, noting how some common name games that he experienced failed to take into account proper pronunciation. With names that aren’t pronounced as they look on paper, such as Hernan, games where students connect their name with an object aren’t always the best.

“Since the ‘H’ in my name is silent, it doesn’t really work and it makes people sound out the ‘H’ in my name,” Maldonado said. “Knowing [how to pronounce] a person’s name is important, especially if you are going to be in the same class as that person for an entire school year.”

Vijayakumar noted that his experience with names and introductions changed after going to university, as he was exposed to more people from diverse backgrounds with unique names. He says it is important to take the time to learn how to accurately say someone’s name, emphasizing how it is a sign of respect and acknowledgment of a classmate’s identity.

“I think that it’s the first step to building a relationship; if you know their name, it’s like, ‘Oh, they actually care,’ and it’s awesome,” Vijayakumar said. “If teachers can pronounce your name if you have a hard name, it’s the first step in connecting with a student.”

“I think that it’s the first step to building a relationship; if you know their name, it’s like, ‘Oh, they actually care,’ and it’s awesome,” Vijayakumar said. “If teachers can pronounce your name if you have a hard name, it’s the first step in connecting with a student.”

Jariwala agrees with this sentiment, sharing how when students say things like “call me whatever,” she encourages them to think about what their name means to them. She also makes sure that her students feel like they are in a safe space and are referred to by what they truly want to be called.

“I feel like the initiative should be there, and the expectation that names and pronouns are still important,” Jariwala said. “At the start of every semester, [I] switch groups and try to have everyone introduce their names and pronouns, just so people are constantly hearing how [a classmate’s] name is pronounced. I always feel like the name is our first sign of showing respect, so [we need] to make sure we are taking the time to pronounce the name correctly.”