Glass Child

Exploring how mental illness touches the lives of siblings

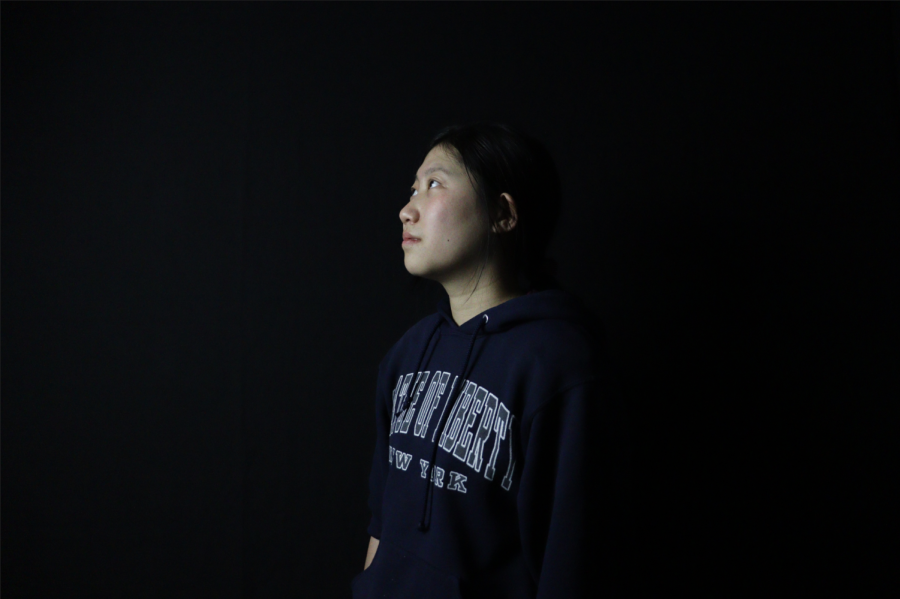

Glass children are often overshadowed by their siblings, even when it is unintentional.

February 17, 2023

One of my family members was diagnosed with anxiety and depression earlier this year. It’s been a learning process since then, as my family and I learn to navigate through life in light of this discovery.

But what I remember most vividly from that time was during finals week, when I asked my parents if I could go get coffee with my friends before school. I thought it’d be an easy “yes” from them — I’d finished all my finals and had little to no work left, and I was excited by the prospect of going out for an informal celebration with my friends. To my surprise, my dad hesitated. My sibling hadn’t finished her finals and he didn’t want the possibility of missing out on a group activity to stress her out. We argued, and ultimately, he conceded begrudgingly, saying that if I really wanted to go, I could go.

Now I knew for a fact that my sibling wouldn’t have minded if I’d gone. I knew that I really wanted to go. But the weariness and tension I saw lining the creases of my dad’s face were what changed my decision. I knew my parents were stressed and tired; who was I to contribute to that? In the end, I stayed home.

This desire to not burden one’s parents is commonplace for siblings of those who have mental health issues or disabilities. There’s a name for it: “well-child syndrome,” or “glass children syndrome,” most commonly described as feeling overlooked or invisible in relation to the sibling. Some may feel that they have no right to voice their concerns because their sibling is struggling more. Some feel the need to work harder, to present as society’s conventional image of “normal,” in order to make up for any perceived deficits in the family. More often than not, they might feel jealous or inadequate, or that the situation they’ve been dealt is unfair. But these problems often go unseen and unheard. That’s where the moniker “glass children” comes from – it’s easy for people to look straight through them.

This feeling of disregard is in no way intentional. It is not done out of malice. In fact, often it’s unavoidable: the nature of being sick simply means requiring more attention. Friends and family don’t intend to foster isolation — however, intention never implies results. Research shows that well-siblings do tend to keep concerns to themselves in an attempt to prevent further stress to parents, and that some may even feel resentment toward their family or sibling.

In the last few years, MVHS has emphasized understanding mental health and how to support someone who might have mental health challenges. Make no mistake, that is good — we should continue to teach about and normalize subjects such as mental illness and therapy. The curriculum simply needs to encompass more. Mental illness is so much more far reaching than simply the scope of a person themself. Explaining how issues with mental health can affect the entire family, or just acknowledging that having a sibling grappling with mental illness doesn’t prohibit them from having their own struggles, could help combat this perception.

Family is often the first line of defense, the most important support system for those who have mental illness, yet there is often no support for the family. It is crucial for families to learn how to nurture their own mental health and for others to learn the same. Only if one’s family members feel healthy and happy can they turn and offer their support and attention to others.

In the end, mental illness affects more than just the person it afflicts — its influence imprints itself on the lives of the people who surround them as well. Educating people on the impact of mental illness outside of the narrow confines of just the individual person is only the first step.

It’s easy to forget that sometimes, it’s the ones that are the quietest who are struggling. Just because someone says they’re fine, doesn’t mean it’s true. If you have a friend that has family or friends with mental illness, make sure to be there for them too. Offer them a chance to vent, or invite them on a fun outing. Tell them how much you love and appreciate them.

And if you’re the aforementioned “well-child,” this is your call to go do something special for yourself. Hang out with friends on a weekday. Go watch a movie. Or do what I ended up doing, and go get yourself that cup of coffee in the morning before school. You deserve it.