Feedback feels uncomfortable

Reflecting on my feelings of awkwardness when giving and receiving criticism

March 16, 2022

“How do I put this? The essay doesn’t really have substance. You probably need to rethink the central theme.”

Bam. The criticism from my writing teacher hit me like a slap. I looked down at my lap and felt my cheeks burn. After spending hours writing a five page literary analysis essay, I had hoped, even expected, to receive validation for my efforts.

“Oh, OK,” I said, trying to seem calm while panicked thoughts of self doubt raced through my head. Why’d she say that? Did I just waste all that time? Am I just a bad writer?

Growing up, I always had to be the perfect child. A huge part of my identity has always included being a good student, pleasing everyone and avoiding criticism at all costs. My parents have always placed high expectations on me as the older sibling. When my younger sister quit swimming and dance class, I was not allowed to. As a result of the constant pressure to excel, I developed a strong desire to seem perfect and likable to everyone, even though internally, I found countless ways to put myself down.

Year after year, I retracted more into my shell, growing fearful of criticism. Even when someone was just trying to help me without malicious intent, I would perceive their comments as negative and indicative of my inadequacy.

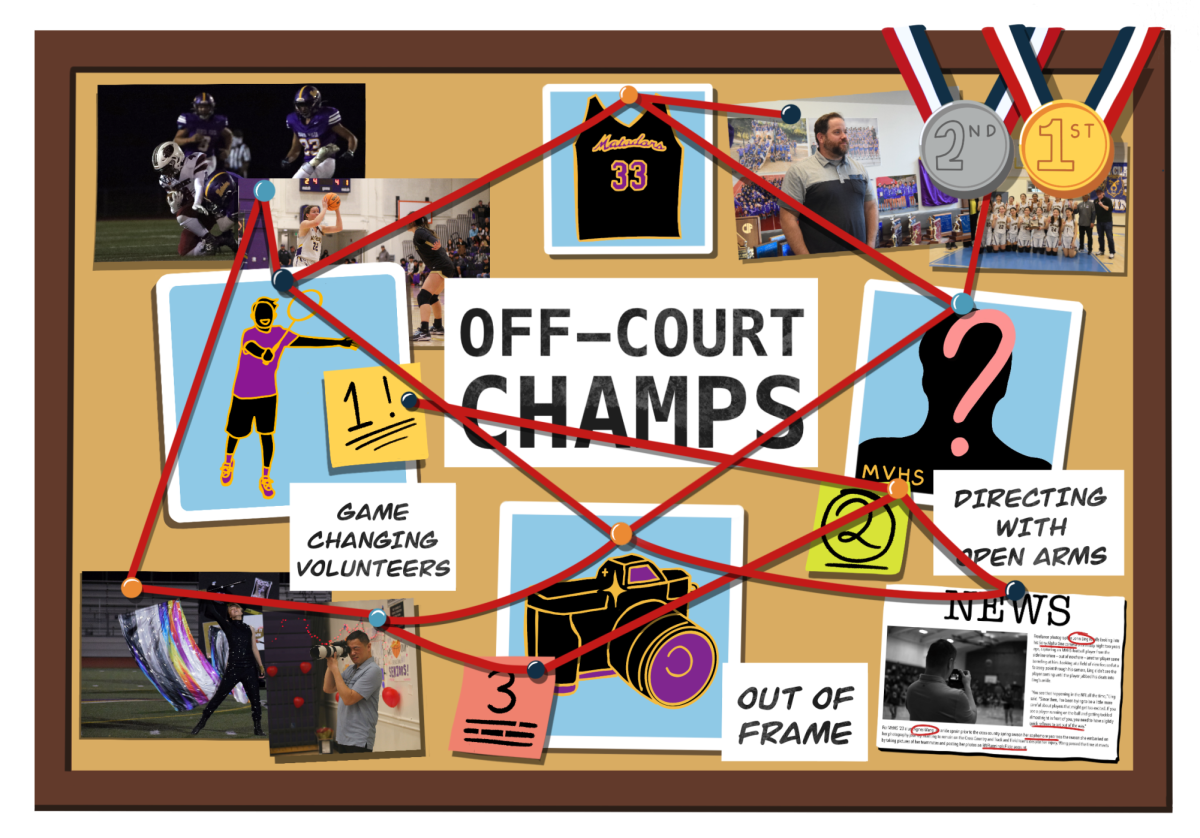

In the spring of my sophomore year, I volunteered for my youth orchestra’s mentoring program, where I worked with a group of younger kids who played the same instrument as me — the clarinet. One week, I was paired to teach the kids with a senior who had more experience teaching clarinet than me.

“Angela, do you have any feedback for them?” He asked suddenly, following a run through of a piece.

Three middle schoolers turned towards me, evidently expecting insightful comments on their playing.

“Oh … um … Why don’t you try playing it a little more staccato and separated?” I quickly suggested, blurting out the first thing that came to mind.

“Actually, I feel like they need to make the notes more legato and connected,” he said. “This piece has to flow and feel graceful, not stately.”

“Oh, OK, yeah,” I stammered. “Sorry.”

For the rest of the mentoring session, I let the senior completely lead the rest of the lesson, giving vague comments only when he invited me to participate. Who am I to give feedback? My playing and musical knowledge isn’t qualified enough. I don’t deserve to be here.

The same insecurities and self doubt that caused my fear of receiving feedback prevented me from giving feedback as well. My low self esteem caused me to be scared of other’s opinions about me.

It wasn’t until the summer before junior year that I actually acknowledged the problem. After a long tennis practice, the first thing my dad told me after he picked me up was, “I think you should try putting more power behind your strokes. I was watching you play, and it seems like you hit very slowly.”

“What do you know?” I snapped. “I hit perfectly fine!”

“Hey! Watch your tone! Am I not allowed to say my opinion?” my dad said. “I’m only trying to help you.”

“Oh,” I said, my face flushing in embarrassment. “Sorry.”

I was tired, sweaty and irritable after practice, which probably accounted for my rather aggressive reaction, and despite the fact that I felt that it was partially my dad’s fault for choosing such an awful time to make such a remark, it got me thinking: why did I react so strongly to his suggestions for improvement? I reflected on other instances when I had received criticism from others and realized that my bad response to feedback was a recurring issue.

After meeting with my writing teacher about my essay, I sat at my desk and stared blankly at the wall. As I realized the magnitude of the changes that I had to make to my writing, I wanted to back away and just trash my entire essay. My essay will never be good enough. There isn’t enough time to make these changes. Why bother …

Wait.

I shook my head, pulling myself out of the ruminative spiral. I could either quit and give up, or I could accept my teacher’s feedback and keep

trying until I improved. As soon as I logically laid out my options, I immediately knew which choice to make. I took a deep breath, snapped on my computer glasses and opened up Google Docs. After slowly addressing my teacher’s comments one by one for several hours (with multiple YouTube breaks in between), I completed my second draft.

A day later, I was back in the same Zoom room, my palms sweating while my teacher read my essay with furrowed eyebrows and a frown on her face. A few moments later, she looked up.

“Your essay is better than before,” she said. “But it still needs work.”

I let out the breath that I was holding. Although I was still a little disappointed, I knew that I had the ability to move forward. “OK,” I said. “What do you recommend?”