What it means to dress differently

Exploring opinions on the connection between fashion and gender/sexuality

February 16, 2022

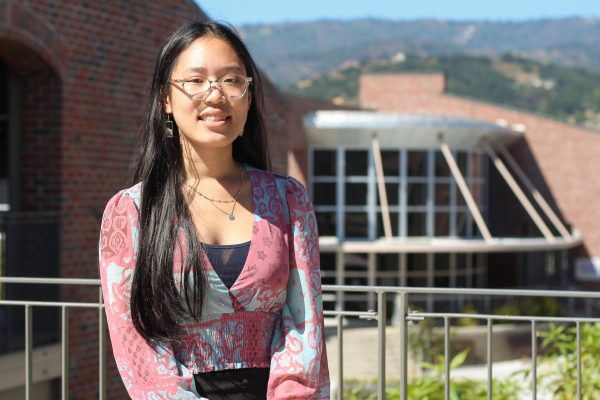

As a child, sophomore Lemon Liu was often mistaken as a boy, and even now, their appearance sometimes leads to confusion over their identity. She can recall multiple times when people used he/him pronouns for them or assumed they were a cisgender boy, presumably based on their tall stature, short hair, streetwear, and K-Pop inspired fashion.

“I found it a little bit uncomfortable because I didn’t want it to be the first thing that people realized [about] me,” Liu said. “It was always something that they pointed out without knowing who I am as a person.”

When they were younger, Liu often wore clothing passed down from their cousins or their mom, most of which was more feminine. As time went on, they began to realize that they felt more comfortable in androgynous clothing, like loose dress pants, baggy t-shirts and combat boots, rather than dresses or skirts.

“I questioned [whether] I actually really wanted to be in these dresses, or [if] it [was] just, all these pretty girls are wearing them, [so] I should be wearing them as well,” Liu said. “I figured out that it could make them confident, but it doesn’t necessarily make me confident.”

Now Liu’s fashion sense is broad: they wears anything from fitted suits imitating K-Pop stage outfits, to sweater vests that emulate a school uniform, to East Asian fashion trends, such as the wolf cut or soft casual wear. Liu’s clothing choices aren’t meant to display their gender, but rather serve as a source of confidence.

Senior Max Hu has a similarly eclectic style, picking his clothing based on a theme, such as academia, punk or goth. When shopping, he looks for clothing in the men’s and women’s sections.

“I want to look good,” Hu said. “Of course, whether I want [to] look cute as hell [or] I want to look extremely handsome today, I will just pick out clothes that work towards that, no matter what those clothes are marketed [as].”

Hu himself struggled with wearing more feminine, or not traditionally masculine, clothing, due to stigma around dressing differently from social norms.

“[Some] people can get uncomfortable. [There’s] sort of this, maybe even fear [or] just discomfort in the area. And that, in turn, reflected back on me,” Hu said. “And, of course when I first started really trying to be more comfortable myself, that was a challenge to me.”

Senior Dominic Wang, uses fashion as a way to express their gender identity, often wearing more traditionally masculine clothing, with a punk or emo style, to avoid gender dysphoria as a transgender person as well as “look good.” Having that outlet is especially important to people who are questioning — those who are unsure of or trying to define their gender and sexuality.

“A lot of times the first thing you do is you experiment with your gender expression, you experiment with your sexuality, how people refer to you,” Wang said. “If you see someone who is experimenting and you as a cis-het [person] automatically go, ‘That person’s queer,’ then that sort of stigmatizes it towards people who are just trying to experiment and figure things out.”

Hu believes that fashion shouldn’t be and isn’t indicative of someone’s gender or sexuality, simply because, by definition, appearance has nothing to do with these facets of one’s identity. To him, these associations are limiting and “strip people of their personal identity.” In addition, he notes that these ideas are hurtful not only to people who are non-conforming but also to those who are cisgender or heterosexual.

“Because as people, we’re not very hard fit definitions,” Hu said. “Trying to push these hard boxes and labels onto these undefined, loose personal choices, just limits how we view each other and how we view ourselves.

In contrast, however, Wang unconsciously associates certain styles with being LGBTQ+ because of how they are inherently linked to the queer community.

“I think it’s interesting that queer people have developed kind of like a vernacular in order to tell people that they’re queer,” Wang said. “At this point, eyebrow slits and undercuts and stuff have kind of become synonymous with being queer.”

Wang points out that often, people are quick to praise non-LGBTQ people for dressing in non-conforming styles while forgetting their queer origins. They reference Harry Styles, “[a] straight man — at least that’s what we know of him,” who often incorporates feminine clothing into his style, as an example of how styles with queer origins are often introduced to the mainstream without any acknowledgement of their history.

“It irks me that people like that get the credit when most of this style was pioneered by drag queens, by actual queer people,” Wang said.

They believe that although clothing shouldn’t be restricted by gender or sexuality, it’s important that people acknowledge these origins rather than “passing it off as their own,”, or glorifying those who dress differently as special or outstanding.

Despite this, Liu believes that “a certain piece of clothing [shouldn’t] just belong to a certain group or a community when it’s just a piece of cloth.” Having been heavily influenced by K-Pop, breaking gender norms is something that they see as simpler than most people might think.

“A lot of the time, people characterize clothing into [masculine or feminine],” Liu said. “But in the end, I still feel like there’s a large portion of clothing in general that [is] a lot more androgynous than you think.”

As someone who struggled with strange looks and fear of dressing differently, Hu has learned that people can’t be forced into hard-fit definitions. Especially when it comes to fashion, sometimes there isn’t a way to relate a piece of cloth to one’s identity.

“If someone wants to look good, whatever, that’s their choice,” Hu said. “There’s nothing you need to do. However convoluted, you don’t need to understand even if it doesn’t make sense. You shouldn’t have to, because that’s their life.