Clinical psychologist Holly Marie-Arce breaks down the differences between depression and sadness

Investigating the differences between “synonymous” terminologies

Graphic by Annie Zhang

November 21, 2019

In the 21st Century, tech savvy Gen Z fanatics and social media enthusiasts express themselves in similar ways. Through perpetual social media streams, blog posts and satirical humour, students find themselves throwing out terminology with overlapping definitions interchangeably — sadness, depression, regret, misery and grief — and use each with the same intent to verbalize their feelings.

A concept known as “wannabe depressed,” coined by 16-year-old Laura U. in an article in The Atlantic, is defined when individuals often “blur the line between depression and commonplace negative emotions,” such as grief and sadness. According to Laura, this ambiguity makes it difficult to “tell what’s wannabe and what’s clinical depression.” We often say a slew of phrases that seemingly have the same surface level interpretations, yet have such paramount differences.

“This homework assignment is making me depressed.”

“I didn’t do well on my last chemistry exam — I’m so depressed.”

“I’ve never been so sad in my entire life.”

According to the American Psychiatric Association, sadness and grief are “usually maintained” in moderation — in grief, “painful feelings come in waves, often intermixed with positive memories of the deceased” or other reasons for the grief. However, in major clinical depression, “mood and/or interest (pleasure) are decreased for most of two weeks,” though people may experience symptoms for much longer.

According to licensed clinical psychologist Holly-Marie Arce, though people conflate sadness and depression, there’s a difference between “feeling emotion” and being clinically depressed. Arce explains that one of the two main symptoms of criteria needs to be met to be clinically diagnosed with major depressive disorder — feeling down for over two weeks or more and/or the inability to feel pleasure from recreation that students usually enjoy. According to Arce, symptoms that fall under depression include changes in sleep, weight, motivational patterns, concentration and confidence — factors that disrupt everyday functionality from showering to attending class.

Sometimes when people feel sad, they can feel some of these other symptoms as well, but still not meet criteria for depression … You can feel sad, and you can have other symptoms, but if you’re still functioning pretty well, then that’s not clinical depression either — that’s sadness.”

Students say they are sad, and then they tend to feel better. They say this because it’s true — they felt dejected for a momentary period, sleep it off and are now back to “normal.”

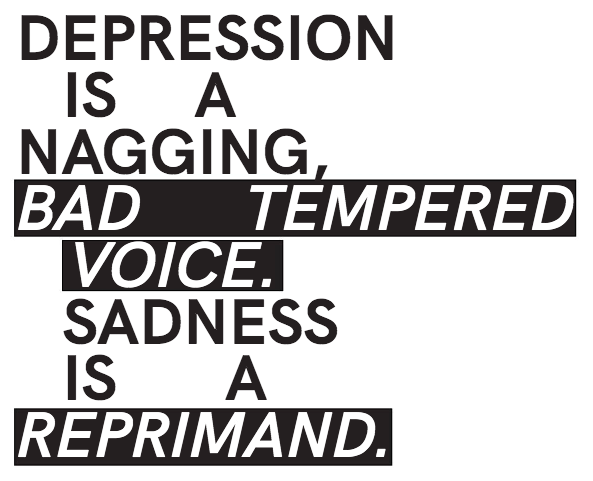

However, when students are depressed, the next day they will likely not feel better. They don’t feel burnt out for a moment — they feel like a hollow shell of themselves. They can’t sleep depression off and go back to “normal” as they can with sadness. Depression is a nagging, bad-tempered voice that rattles the depths of one’s consciousness. Sadness is a reprimand.

Though we are all trying to formulate our jumbled thoughts into words and ground our abstractions, it’s important to differentiate the blurred lines between synonyms. The word “depression” carries a language asset — when people who are not undergoing mental rehabilitation inaccurately and humorously dub themselves as depressed, they are undermining the gravity of mental health.

“There’s times where [depression] can be humorous, but there’s also times where it needs to be taken more seriously,” Arce said. “And I think as humans, we have a tendency to go into extremes; not take it seriously enough, joking about it, or telling someone, ‘No, you’re not depressed.’ Screw it, but they are depressed.”

While we may perceive such words as alike in their technical definitions, we need to identify the differences between synonyms in order to provide a safe environment for people who struggle with mental illnesses. Arce believes that there should be more education on differentiating between depression and sadness.

“

People aren’t familiar with the clinical criteria of depression,” Arce said. “And so they can basically invalidate somebody who’s going through something really hard … or, we can swing to the other side and call somebody depressed when they’re actually doing really well … it can be harmful to label somebody, [whether] if they’re a depressed person or not. I’ve seen people who [are] labeled a certain way. They’re conforming to that label, and start doubting that they can do things.”

We need to be aware of how to accurately verbalize our emotions through the correct terminology to create a healthier learning community so that professional help can be directed to those who need it the most.

Depression at MVHS is muddled in a mesh of satirical humor, meme-quoting and over exaggerations because mental health is a taboo in many Asian cultures. By doing so, we shift the social leverage of mental health to offhand commentary rather than preliminary attention. We need to express ourselves properly — sadness is sadness and depression is depression. They are not the same, and we shouldn’t be treating them as so.

By portraying our emotions accurately, as a community, we are able to direct professional help to those who need it, as well as create a support system at the same time. If we continue to perpetuate this cycle of synonymous verbalization, we may be overlooking the weight of mental health in its entirety. It is extremely hard to tell the difference between regular stress or sadness and actual depression, therefore making it harder for people with depression to be seen and given resources and help.

“It’s a good thing to keep talking about [depression and sadness] because then conversations can happen, and then people can get pointed towards the right direction,” Arce said. “I’d rather have people talking about it than not, as it was in the past.”