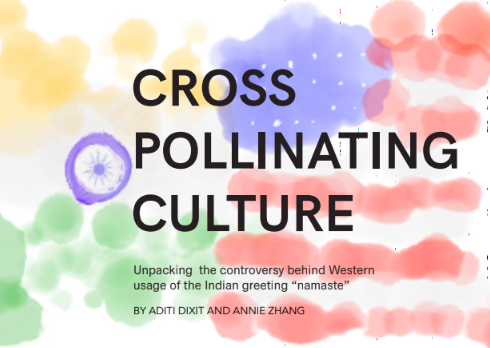

Cross pollinating culture: why the Indian greeting “namaste” should not be popularized in the West

Unpacking the controversy behind Western usage of the Indian greeting “namaste”

Graphic by Annie Zhang

September 27, 2019

Namaste, similar to “hello,” is a customary greeting used by many Indians as a sign of respect towards elders or those of a higher social status. The word is derived from Sanskrit, an ancient Indo-Aryan language, and translates to “I bow to you.”

In a Western context, the salutation is exchanged as a means of closure for yoga sessions to conclude the session. The direct definition of the word is warped to transcend it’s intended translation — in yoga, namaste is interpreted as a means of spiritual elevation. To English teacher Vennessa Nava, namaste is “a mutual kind of recognition of our shared humanity.”

In the 21st Century, namaste is often sensationalized to notions of zen, peace and connectivity. As a yoga instructor, Nava follows a nontraditional yoga practice — she chooses to never use the word to initiate or seal a yoga session.

“In this space, because it’s a workplace, I don’t want to have any religious overtones or undertones,” Nava said. “I conceptualize of leading teachers through a yoga practice as more tending to the side of just relaxation … [although] some of the conceptual underpinning might work its way into the things I say — the queuing, the kind of metaphors that we’re building during the class.”

According to Nava, because America is such a “pluralistic society,” the cross pollination of cultures edges into thorny complications — cultural appropriation and religious microaggressions.

A prominent example of said microaggression is the commercialization of the word namaste in popular media as a pun. One example is “Nama-stay In Bed,” commonly used to mean “Nah Imma Stay In Bed” branded on pillowcases and sleepwear sold in department stores.

Since the practice of yoga takes the greeting namaste out of its intended context, exercising the microaggression may aggravate cultural tension.

“I’m very conscious of being a white woman who practices yoga, which is easily this slot of stereotype, especially when in Western practice of yoga it has been dominated by white people,” Nava said. “I don’t own any clothing that says namaste or anything like that — I wouldn’t wear it. I think it’s in poor taste.”

Indian Parent Janaki Burugula echoes a similar sentiment, believing that usage of the word in an American context is “ill mannered.” She sees the branding of namaste puns as a “marketing gimmick” to attract a crowd, and for consumers to possibly feel connected to Indian culture.

“I don’t think that [marketing/commercialism] is [the] proper way…[it’s like] having our deities — a Ganesh picture on the toilet seat cover or [a] Shiva picture,” Burugula said. “If you put a cross on the pillowcase, how [would] you feel? It’s the same way.”

Although Nava sees such appropriation as a complicated issue with nuances, freshman Sneha Agrawal believes it to be the much simpler case of ignorance.

“I feel like if you’re doing yoga or something, then you’re trying to use [the greeting] as a word of empowerment,” Agrawal said. “But if you’re putting it on a pillow for a pun, and if you don’t even know what the word means … you’re being offensive and you’re not using it right.”

Burugula sympathizes with Agrawal, echoing that the casual usage of the salutation in America has loose ties with ignorance. Though selective individuals may find the greeting as culturally inappropriate, Burugula believes that namaste is simply a “catchy word” and has no religious strings attached in a Western context.

“Some people might get offended by that probably, but I don’t see any reason … unless they actually mean it and they want to demean this,” Burugula said. “I don’t think it’s in any way connected to religion. It’s just a form of saying hello in the local way … you clap both hands and then you say namaste … [like] some kind of tradition passed down.”

With yoga transcending the traditional intent of namaste, Nava believes that complications of certain demographics represent what yoga means in a Western context. Nava views the use of namaste as a microaggression, as it strips the interpretation of what yoga originally was, who it was for and what it was meant to accomplish.

With this in mind, Nava believes everyone can play a part in raising awareness although the gravity of the issue depends on the situation and context.

“I think there are times where you can engage in a little call out culture, and it might be tone deaf,” Nava said. “There can be other times where you just have the perfect opportunity to say something, because that person is likely to be receptive to what you have to say. I think you just have to read the situation, and be attuned to it, to know when that may or may not be appropriate.”