Short end of the stick: Why the Affirmative Action policy should not be shunned

Navigating the purpose of race-based college admission policies

May 22, 2019

Affirmative Action (AA) is a vehemently debated policy — both a milestone for supporters and a grievance for opposers. Over the past couple of years, news relating to college admissions has been largely dominated by the notorious Harvard lawsuit involving its alleged discrimination against Asian applicants. Discussion surrounding the case has often been centered around AA as a nationwide policy, requiring that college admissions officers accept a certain number of applicants of underrepresented minorities like Latinx or African-Americans. Many students, MVHS’ own being no exception, have voiced their opposition to this policy, asserting that it allows colleges to admit less qualified students and “take up” the spot of more qualified students simply because of their race.

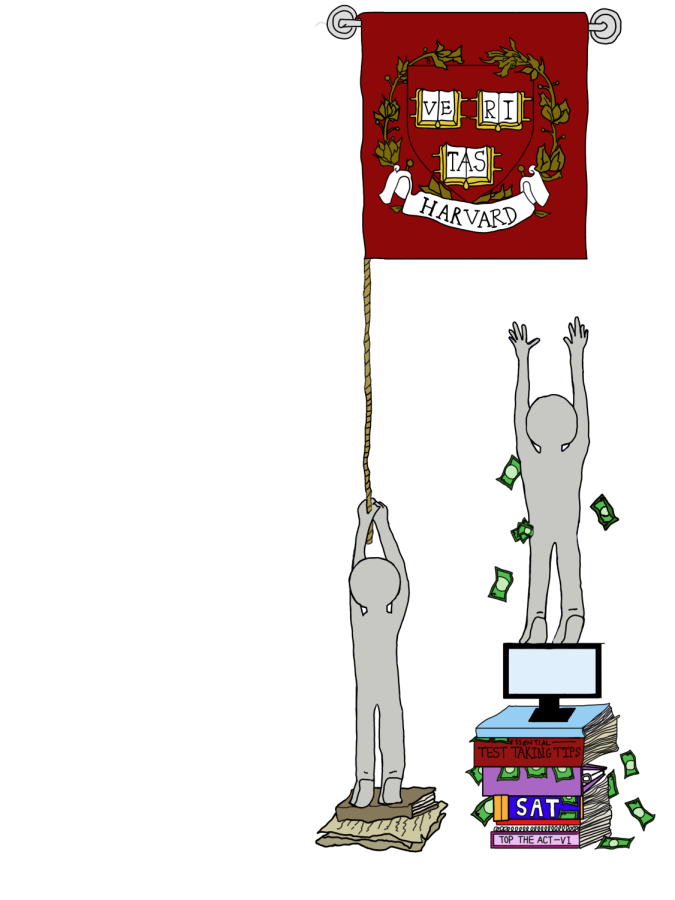

But these preconceived arguments are often made without an understanding of why AA was implemented in the first place. Students at MVHS can ostentatiously argue that they deserve a spot at an Ivy League college, more so than, say, a black student with a lower GPA or SAT score, because we live in an area largely dominated by wealth and privilege. With such wealth and privilege comes plentiful resources that we may take for granted, like private tutors, prep books and off-campus classes.

AA is not for us to drone on about. It is not intended to make easy lives even easier. It is meant to lift those less privileged than us to our level; it is meant to even the playing field, granting a chance for minority groupings with less privilege to go to college.

With that in mind, it’s important to understand that because we boast such privilege, AA is not for us to drone on about. It is not intended to make easy lives even easier. It is meant to lift those less privileged than us to our level; it is meant to even the playing field, granting a chance for minority groupings with less privilege to go to college. As it stands currently, college is one of the most significant ways to ensure that all people have access to the same career opportunities.

A myth shrouding AA is the fact that the 30-year-old policy isn’t as effective in modern society because the playing field has been leveled — but this is simply a crutch to dismiss AA by affluent communities. The turf is far from equal: African-American and white unemployment rate discrepancies have been in gear for more than four decades. At an annual rate of 6.6%, black unemployment rates are more than double that of white employment rates (3.2%). According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in Jan. 2019, Hispanic unemployment rates dropped from 4.9% to 4.3%. With these rifts prevalent in minority groupings, AA is a direct getaway for these communities. While it is not an instantaneous cure to societal oppression, AA allows many to pursue the American Dream — to becoming something from nothing.

To oppose AA because it does not personally benefit us betrays an elitism that excludes underrepresented minorities and classes from the lives that many of us are born into. Just because we aren’t presented with such racial privilege doesn’t mean we have the right to rebuff AA — it is a second chance for underrepresented minorities that have been systematically and historically oppressed. It’s true that the majority of the MVHS student population is not white, and that means that we don’t possess the same amount of privilege that white people have, but it’s undeniable that many east Asians and Indians have at least some form of advantage over, say, black and Latinx students.

To oppose AA because it does not personally benefit us betrays an elitism that excludes underrepresented minorities and classes from the lives that many of us are born into.

We may complain about not getting into Yale, for example, after grinding test prep and extracurriculars for years, but we should be appreciative of the fact that we can afford to spend our time on Speech and Debate rather than working long hours just to make ends meet. We will complain about scoring messily on the SAT after countless rounds of test taking preparations, but we should be grateful at the least for the plethora of accessible resources that are presented to us, in comparison to first generation minorities or low income households. At the end of the day, AA is less a policy that “takes” spots away from people and more a policy that gives others the opportunities that we take for granted.

In our MVHS bubble, we may be enraged at the prospect of Affirmative Action. But understanding AA in the eyes of less prosperous communities is important in order to become less ignorant of the world around us. We have to realize that the only thing we have to lose from a rejection due to AA is ego deflation. Our futures are not entirely closed off — we have options like state schools and transferring to four-year universities after going to community college. For those who AA is trying to uplift, rejection from college is a direct denial of their future. Their options are much, much more limited than ours — we need to take this fact into consideration before we ridicule Affirmative Action. Just because it doesn’t profit us in the college admissions game doesn’t mean that it should go away.