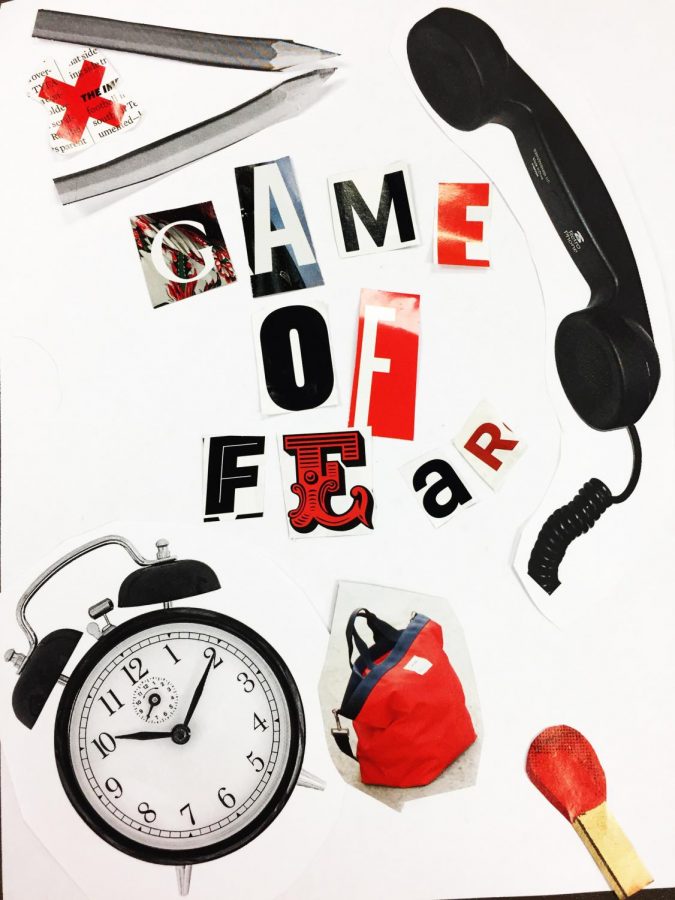

Game of fear

Students describe the experience and impact of receiving hoax threats

May 23, 2018

Fifth period had just begun when Palo Alto HS senior Julia Qiao heard the announcement about a lockdown. She quickly took action, reaching for the lock block in her classroom that would keep the door closed. Working quickly, Qiao began to assist her classmates in barricading the front door.

As she hunkered down and hid in a corner of the room, she texted a group chat that she was in, trying to ascertain the facts in an atmosphere of anxiety and panic. However, that anxiety turned out to be unfounded: Qiao found out 15 minutes later from the Palo Alto Police Department’s Twitter account that the threat of the school shooting had been a hoax.

Santa Clara County, alongside other districts across the state and nation, have been receiving threats of violence. All of these threats however, according to Mercury News, have been confirmed to be part of a hoax. The threats have since been tracked to a cyber hacking group in Switzerland. They take credit for their spread of mass paranoia across the nation, feeding off of the recent school shootings and political divide revolving around gun control.

“My initial reaction was just confusion, and a little bit of annoyance,” Qiao said. “The fact that someone would do this cost a lot of money and caused a lot of emotional trauma. I just think it was stupid.”

On March 29, during Paly’s lunch period, the Palo Alto police received a threat through a phone call, warning that a shooting at Paly’s campus would occur 15 minutes afterwards.

After over an hour, the lockdown was lifted.

Just two days prior to the shooting threat at PAHS, a school nearby, Cupertino HS, also received a threatening phone call.

A few days later, on April 9 and 13, MVHS received two emails with the same threats.

In response to these events, the Santa Clara County Sheriff Office took precautions in order to ensure the safety of students across the district: sending patrol deputies to the schools.

MV’s school resource officer, Cory Chao was sent out to Saratoga High School, and alongside his fellow school resource officers, his number one concern is improving the safety of schools.

“We already have procedures for bomb threats, procedures for active shooters, run and defend methods and all those other drills but we’re constantly updating out drills and our research,” Chao said. “How we get prepared depends on the time, the people; Times are changing so, we have to adapt with the times.”

Principal April Scott took on her own role in informing the student body at MV of the situation.

Once MV received threats, she sent out an email to both parents and students to notify them about the hoaxes. Scott said the school would have a small police presence on campus to err on the side of caution.

Vice principal Andrew Goldenkranz points out that the feeling of fear has intensified over the past 15 years as the general public was met with more shootings, more media attention, and more localized events occuring. While the possibility of school shootings and bomb plantations slowly seem more tangible, there is a discovery of how little everyone knows what to do in such situations.

“What if it happened at lunch, when everyone’s out wandering the campus? And we may have 500 kids off campus… What’s going to happen when we got 2,000 families that are freaking out,” Goldenkranz said. “Every time you think you have a solution, it just open up more stuff you have to figure out.”

Just as Chao said however, the times are changing, and MV has been working on their own drills and methods in case of emergency situations.

“If it’s in the classroom we’re pretty well practiced,” Goldenkranz said. “Part of our plan is having communication teams and a triage team. We have a health team in terms of responding to kids in need, we have a team that works directly with law enforcement, so we actually have an organizational chart of what would happen in that kind of situation.”

Goldenkranz understands, no matter how prepared the school may be for such circumstances, emotional hardship may ensue regardless.

CHS junior Lucy Lue had only a small taste of the panic that arises amist an emergency at school. Initially didn’t hear the evacuation announcement when it came over the loudspeaker during lunch and only realized that the evacuation was in effect when she saw other students leaving en masse.

“The announcement was really quiet and we actually couldn’t hear them,” Lue said. “[It was] only after everyone started pouring out of the classrooms and screaming that we realized, oh shoot, we should get out of here.”

As Lue evacuated her school, she avoided Main Street, which is where most of the CHS students were running. Instead, she took a smaller path away from Stevens Creek Boulevard.

“There were binders on the ground,” Lue said. “I saw a pile of binders just flying across the ground. Everyone was scared and panicked.”

Similarly, CHS senior Tom Xue ran to his house, unaware that the threat was a hoax and under the impression that his life was in danger.

“I was just running away,” Xue said. “I thought it was a dangerous situation for me, so I wanted to find a good way to run out of the school to avoid the shooter.”

CHS students were notified by email later in the day that the threat had been a hoax and that there was never any real threat to the school. CHS sophomore Lillian Kann began taking the seriousness of future threats lightly.

“I think a lot of people started thinking that from now on everything else would be fake, because we got multiple emails and stuff too,” Kann said. “It was just kind of like, okay, this

again.”

The following day when CHS students returned to school, several teachers discussed the evacuation with their students in class, but for the most part, the atmosphere was calm.

“Everyone continued on with their day and everything was back to normal; we didn’t really address it,” Lue said. “I mean, we talked about [the evacuation] in some classes but not all of them.”

MVHS executive assistant to the principal Diana Goularte was relieved after hearing that the threats made against CHS were merely hoaxes but emphasized that vigilance is still necessary.

“Now that we have more information about these hoax attempts, we are not immediately panicked,” Goularte wrote in an email. “We must be still be focused on safety and investigate every threat.”

In contrast to the reaction at CHS, after the lockdown, Qiao described the atmosphere at PAHS as being full of anxiety.

“Afterwards, when we were excused and let out of our classrooms, I still think there was a lot of residual anxiety,” Qiao said. “It was obviously pretty traumatic to think that you might die and then come out of there and you have to go through class. People were still really shaken up, and I don’t think they were able to really believe what happened.”