t was 3 a.m. He and his mother were fast asleep, but his dad was already heading off to work. He wouldn’t hear from his dad for another week.

His dad’s routine of leaving in the middle of the night and returning days later was a part of normal life for math teacher Jon Stark, who grew up during the height of the Cold War. With his dad being in the Air Force and flying daily missions to the Soviet Border, Stark was always aware of the fact that at any moment, his dad could be ordered to attack Moscow.

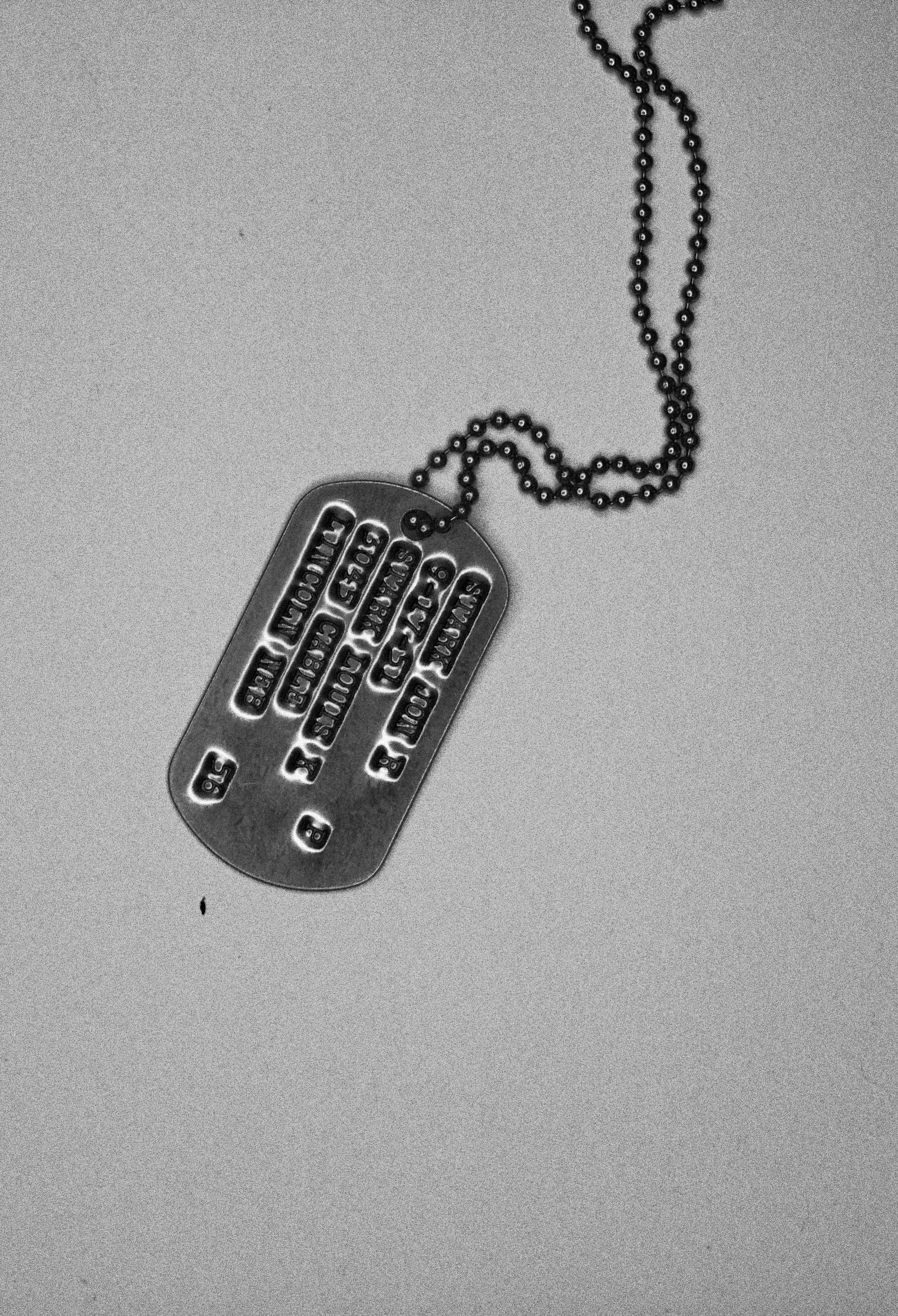

Stark moved from base to base with his family, attending schools where he practiced duck and cover and civil defense drills. He knew friends who had built bomb shelters in their backyards. The Air Force had even given him a set of dog tags with his name on it so that they could identify his remains in the case of a nuclear holocaust. For Stark, and many others at that time, the threat of nuclear war was real and imminent.

After the Cold War, most discussions of nuclear war subsided and until recently, there hadn’t been much talk about the possibility of an attack. But developments in North Korea concerning nuclear missiles and warheads and Trump’s consequent responses have put many in both countries on edge. With drills sounding in Hawaii and articles on how to protect yourself during a nuclear attack, the present growing fear of nuclear weapons has begun to resemble the sentiments of the public during the Cold War, bringing to mind the old adage of history repeating itself.

Still, Stark feels the fear present today is far less prominent or persistent. He explains that back then, an attack was not just a future possibility but a guarantee.

“The attitude was not if something might happen,” Stark said. “We were kind of expecting it – it was a question of how long we could get away without it happening. It seemed to be one of those things where we were dodging bullets all the time. It gave me kind of a warped childhood. I really thought [an attack] was going to happen, and youíre always happy for any day it didn’t.”

Senior Santosh Sivakumar agrees with Stark that there are clear differences between the fear then and now. He believes there is a lack of urgency nowadays when it comes to the threat of nuclear war. Sivakumar explains, however, that there are justifications for this behavior.

“[It] seems like people now aren’t sure what to believe and [what] to decipher from the information provided,” Sivakumar said. “It also seems like attention toward the issue of nuclear war fluctuates a lot.”

But Sivakumar also understands that whatever little fear there may be, it should be allowed at this time, when there is so much uncertainty present.

“It’s definitely justified, especially when it’s so hard to come by clear, reliable information – people have a right to express their fears and to desire safety,” Sivakumar said. “It definitely sucks to have to grow up in a time where the worsts of history repeat themselves, and I only hope that this period will quickly subside in a safe and transparent manner.”

Even for those who didn’t live on Air Force bases, the threat of nuclear war hung above their heads. Class of 1973 MVHS alumnus Lea Hutchison describes how, although people never talked about it much, most people expected the bomb to be dropped at any time and didnít feel there was anything to be done about it.

“We never really talked about it, it was just kind of this attitude of fatalism,” Hutchison said. “We just all figured, ‘Hey, if the bomb was gonna drop, then we weren’t gonna be there to even know about it.”

Living on an Air Force base, Stark’s proximity to the threat of war was closer and thus likely influenced his childhood more than the average kid. But in general, he feels the lack of information regarding international affairs and the employment of the draft made the fear of a nuclear attack much more tangible for his generation.

“It doesn’t have the same immediate direct reality for them that it did for me,” Stark said. “It’s a different notion here when kids don’t even have the fear of getting drafted. I don’t think it has been internalized by kids here. I don’t think it’s part of their conscious daily thinking.”

Despite this, Stark admits that today’s political climate does give him flashbacks to his childhood every once in a while. But rather than seeing this as history naturally repeating itself, Stark believes people actively push for a repeat of the past.

“There’s been a big movement lately about making America great again. What does that mean? You’re looking nostalgically at a past era, seeing what you liked about that or what you’ve imagined about that, and are trying to bring it forward,” Stark said. “There’s a conscious attempt to repeat history, but it’s a distorted view of history. It’s not the way things really were.”

Stark also explains that he is forced to acknowledge both the good and the bad parts of history seeing as he lived through a lot of it. This helps him not look back in a distorted fashion in which everything worked out the way they wanted. He understands that while the past may have been easier in some aspects, in many others, things were worse. He cited examples of various diseases like polio and cancer that used to be untreatable, and the fact that women and African Americans also had little to no job opportunities and could practically get nowhere living in this supposedly “great” period of time.

“People actually consciously try to repeat some aspects of it, and along the way they drag some things that are not so good. It doesn’t sit well with me,” Stark said. “I know how narrow that knife edge we walked before was. I don’t want us stepping back onto another knife edge.”

Hutchison, on the other hand, sees history as both organic and cyclical, with attitudes towards issues like immigration and civil rights swinging back and forth like a pendulum. She points to the recent developments in the womenís rights movements as an example of this.

“We get the vote [in 1920] and the movement went into a dormant period for a time, and then it came back loud and proud in the early 70s,” Hutchison said. “There are times where things go into dormancy and there are times where things go into ascendancy.”

Although she believes that history naturally has lulls and resurgences in attitudes, Hutchison still feels change is possible – that we don’t always have to repeat the past. She feels that there is more transparency nowadays, which makes it easier for the public to call foul and that helps to change the situation.

“I think that when it comes to history repeating itself, it can – but it doesn’t have to,” Hutchison said.