All students are entitled to their education. The Constitution itself protects a childís right to have equal access to it. But when it comes to where students get their education from, this is where problems begin to arise. Because of students having a strong desire for the best education they can attain, there have been cases where students or their parents have faked their residency to attend a certain school.

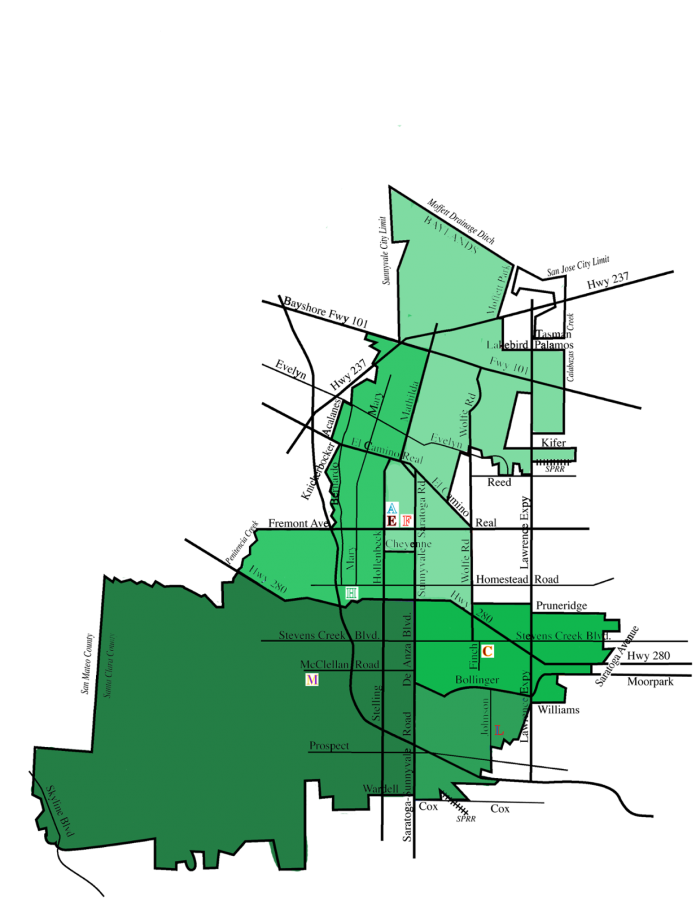

According to manager of Enrollment and Residency for FUHSD Julie Darwish, there are several requirements for students to prove their residency. Each address is assigned to a school based on their area, regardless of the city boundaries. In order to prove the student lives within the boundaries, the parents or guardians of the student must fill out a Residency Declaration form, which states any previous locations of residency or other property they own. In addition, parents must provide ID, a vehicle registration, a property tax bill and a PG&E bill. Parents must go through this process twice: once when they enroll and again during their sophomore year.

Darwish said the reason why it is important to check for residency is because the school runs on local property taxes. FUHSD is a basic aid district, meaning the number of students who attend the school does not influence the amount of funding the school receives, a completely different setup than revenue limit districts. Revenue limit districts receive money from the state for every student who attends their school. But if the number of students increases at a FUHSD school without proportional payment, resources will simply be spread out thinner amongst the students, which could compromise quality of the education. In order to keep the resources concentrated on the local residents who pay property taxes, the district tries to identify false residents to avoid thin distribution of their resources.

“It’s our responsibility to the taxpayer, the local resident, we are diligent to make sure that the students we serve truly live here,” Darwish said.

Yet Darwish said the district is limited on resources to find those illegally attending the schools. With only one investigator, she says it is impossible to track the residency of over 11,000 students.

“So we admit, we accept that fact that we cannot catch everyone,” Darwish said.

Last year, the district caught 350 students whose registered addresses did not match the ones where they actually lived. Out of those 350 students, 100 were disenrolled. While this may seem like a small number, Darwish explained that even though the number of students she catches faking their residency doesnít seem like a large amount, in the long term, it accumulates to huge savings for the school.

There are several exceptions to this policy. According to Darwish, there are some students who receive senior privilege. This means if the student has a good behavioral and academic record during his or her first three years of high school, he or she will be able to attend the school even if they move to a different district. Students who are homeless are also provided with free education, given that their status is verified by the district. In the case that the studentís parents are divorced or separated and live in different districts, as long as the parents have shared custody, the student is allowed to decide which school they want to attend. However, if one parent has full custody, the student must go to the district of the parent with custody.

Calculus teacher Jon Stark has been teaching at Monta Vista long enough to witness the effects of the commencement of the residency checks in 2005. Controversies arose regarding students outside of the district boundaries attending FUHSD schools, eventually leading to a financial barrier as more and more students began to sneak into schools. In response, the district and teachers union set up a contract which instituted a residency monitoring department. An office was set up in the district office, with staff whose only purpose is to check for false residencies. Stark said that this establishment proved to be very effective, as there was a decrease of false residency issues in the school population after it was implemented.

Once residency monit oring started, the staff began investigating the studentsí addresses. Stark said that in some cases, the staff would find that students would be living on their own without adult or parental supervision, their guardians were either in a different town or in a completely different country. Students or their parents made arrangements to pay the owner of a home in exchange for the use of the house address. In other cases, people manipulated their electricity bill, such as by having a light bulb switch on and off within a certain period.

oring started, the staff began investigating the studentsí addresses. Stark said that in some cases, the staff would find that students would be living on their own without adult or parental supervision, their guardians were either in a different town or in a completely different country. Students or their parents made arrangements to pay the owner of a home in exchange for the use of the house address. In other cases, people manipulated their electricity bill, such as by having a light bulb switch on and off within a certain period.

“There were some places where people would set up an address, and that address, if you checked the school records, would be the home to about 40 or 50 teenagers,” Stark said.

Darwish said these numbers were unlikely, but could be possible due to sharehouses hosted by caregivers. Caregivers are adults who are 18 years or older who are qualified to take care of minors. Each caregiver situation is examined to check for student welfare. As each caregiver only has to be as old as a college student, their motives could vary. Darwish said that there could be cases where a caregiver takes care of multiple students, which gives the appearance of many teenagers living in one house. While some may genuinely treat the minors well, others may only want to become caregivers to collect money. She has seen one situation where the child’s sister was taking care of him, their parents living overseas. With no one to supervise them, the student didnít attend school as his parents thought he was doing. Because of these possibilities, all caregiver situations are looked into by the school district.

Although there are fewer cases of faking residency, it is still an occurrence in the district. Students or their families have various reasons for engaging in this action. One student, who wished to remain anonymous, had falsified their residency for a month in order to attend a middle school. They said the decision was made by their parents, and that they had no say in the process. Their parents had chosen that particular school over others because it was one of the highest ranked schools and it was highly recommended. Since they had a family friend who was currently attending the middle school, their transition was easier as well. They had only used this friendís address for about a month before actually moving into the area and becoming residents who lived within the district’s boundaries.

“I don’t know what the alternative option was,” the anonymous junior said. “It wasn’t really a choice on my part.”

“My mom pays $700 a month for me to come here and my dad is always complaining about how expensive it is, so I’d like to work hard so that my parentsí money doesnít go to waste,” the anonymous junior said.

Stark has known some students in his class who forged their address and were forced out of the district once the policy was implemented. Although he felt sad that they had to leave, he believes that it is not right for a student to deprive others from resources just for the sake of coming to an FUHSD school. By pretending to live in the area in order to attend a school, the student is taking the services paid for by local taxpayers. As a large amount of money is put into the education of each student, Stark said it is only fair to use the money towards students living in the local area who are legally attending the school.

“If you don’t live here, you should support the district you’re in and make it better,” Stark said.

Additional reporting by Sara Entezar, Ilena Peng, and Sepand Rouz