In 1968, radical feminist Valerie Solanas attempted to murder Andy Warhol. Throughout history, women have fought for voting rights, education and basic working conditions under the premise of feminism, the belief that men and women deserve equal rights. But, at least at MVHS, the drive to continue the fight for female equality has diminished. Sixty percent of students in MVHS do not consider themselves feminists.

The disparity between men and women is fairly evident. The Pew Research Center released a study in 2009 titled “The Harried Life of the Working Mother” which showed that in 2009, women made up only 47 percent of the work force. In another Pew Report from 2008, “Men or Women: Who’s the Better Leader?” Americans rated women as superior to men in honesty, intelligence and compassion, among a few other traits, but only 6 percent of those surveyed said women would make better political leaders.

And let’s not forget the income gap: in December 2010, according to a presentation by the Joint Economic Committee, women only make 77 cents for every dollar a man makes. While there has been significant progress in things like the composition of the workforce — in 1950, less than 30 percent of the workforce was comprised of women — the income gap hasn’t shrunk down by much since 2001.

“[It’s] better than before, but not there yet,” said senior Wen Lee. “In business and jobs, the high-pay and high-level business jobs are usually dominated by men.”

Therefore, groups and organizations geared toward women, like the Women in STEM club at MVHS, often pop up. The club’s intention is simply to support women, but organizations like these are often misinterpreted as excluding men. Treasurer Joyce Tien points out the main purpose of the club has little to do with men at all: They just want to encourage girls to pursue careers in STEM fields.

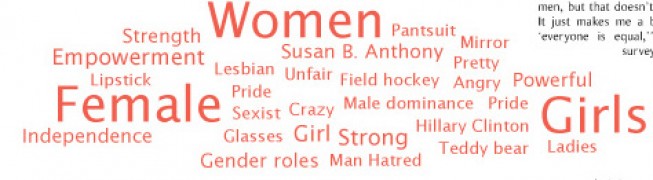

But despite the numbers, MVHS students generally view feminism, which could potentially counteract those discrepancies, in an unfavorable light. While 44 percent of respondents said there was no particular connotation to feminism, 37 percent said there was a negative connotation, and only 19 percent said there was a positive one. That hesitancy seems to come from not wanting to fall under the same label that many bra-burning, not-shaving-my-legs feminists seem to fall under: one of militancy.

The definition of what feminism really means is often misconstrued as hatred of the opposite sex. Junior Tanya Rios sees feminists as women who either think they are “the same as men or … above men.” So although many do support women’s rights, they group themselves with non-feminists.

Tien is also reluctant to label herself for fear of connecting herself to the stereotype. According to her, she and the other officers of WiSTEM don’t want to call themselves feminists because they don’t want to be seen as resentful toward the other sex.

“I definitely stand up for my rights,” she said. “But I don’t see myself as a feminist, as if ‘I hate men.’”

While it comes up less frequently than the idea of misogyny, misandry, the dislike or even hatred of men, is still a relevant issue. A book published in 2001, “Spreading Misandry,” by Paul Nathanson and Katherine Young, two religious studies professors at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, looked at the widespread hatred toward men in everyday culture. The two published a sequel in 2003, “Legalizing Misandry,” that looked at the same issue in laws in North America.

A large connection to the negative connotations is media. The propaganda shown to teeangers and adults gives the average way to act and look in every situation. As a teenager, it is crucial to conform within the school and media creates the guideline to never embarrass oneself.

“Media generally is against feminism,” junior Marina Nguyen said. “You will be watching shows and there will be two females and the only thing they are talking about together is another male because of love triangles. There is something called the bechdel test online where it is this test to show if there is any part in the show or movie where two females talk about something that is not a male, and generally most media doesn’t pass it.”

While news of feminism reaching Solanas-level extreme hasn’t come up recently, there is still a general wariness, especially among male students, towards feminism. Of the 287 male respondents, 74 percent did not consider themselves feminists. Of the 385 females, on the other hand, a smaller, though still significant, 48 percent said they did not consider themselves feminists.

“There’s a conception held by some that to be pro-female is to be anti-male,” said English teacher Mark Carpenter. “I think that in the last 20 years or so … that conception has kind of migrated to the periphery, but I think it still exists … To acknowledge the history of advantages that men have had and to try to rectify that is thought of somehow as anti-man because you’re taking something away from them.”

Senior Sagaree Jain, who considers herself a feminist, also finds that when she brings up the subject with men, they often get defensive, interpreting it to mean supporting women at the expense of men.

“It’s as if you’re attacking them,” she said. “People get confused and worried, so then you get words like ‘femi-Nazi’ floating around. All [feminists] are looking for is basic equality.”

She thinks there’s a much plainer definition of feminism that what most would assume.

Feminism is, at its roots, the advocation of equal rights for men and women. It doesn’t have to do with pro-female or anti-male sentiments.

A male survey respondent wrote, “As long you actively want men and women to be treated equally, you’re a feminist.” Another female respondent wrote, “A feminist is anyone who believes in male and female equality. Unless you tell yourself you can’t say or do something purely because of your gender, you are a feminist.”

Still, the reluctance to associate with feminism is pervasive even among women, 38 percent of whom surveyed said feminism had a negative connotation.

“Of course I feel that women should have equal opportunities as men, but that doesn’t make me a feminist. It just makes me a believer in the motto ‘everyone is equal,’” wrote one female survey respondent. “I have no problem with cheerleading, which many consider to be a sport that’s demeaning to women, and I certainly don’t feel the need to spout ‘women are strong’ chants everywhere I go.”

But, maybe those so-called radical ways should be more accepted. What we now consider natural for women was once considered extreme.

“There have been times in American history where the notion of a woman having rights was a radical concept and that was a time that called for radical feminism,” Carpenter said. “The idea of it being normal for a woman to have a job and a career and an education was a radical idea, and radical feminism was a necessity. At this point, what do I consider radical? What do I consider extreme, too far? I don’t know. I think that it has to go far enough to ensure equality.”

Perhaps the real problem is lack of awareness about what feminism really means. The reason why feminism has a bad rep isn’t necessarily because of what it stands for, but what people wrongly assume.

A female survey respondent said, “I support feminist movements and female rights. I think there’s a negative connotation that comes with admitting feminist inclinations, but at heart, I am a feminist and proud of it.”