Throughout her 23 years of teaching at MVHS, freshman Biology and Physiology teacher Lora Lerner says she has learned not only how to grade but also the proper approach to teaching incoming high school students. Instead of treating every high school student equally, no matter the grade level, Lerner has realized that freshmen will often not have the experience to adjust to a high school level course in the first semester.

She and the rest of the Biology professional learning community have created a way for freshmen to adjust their first semester grades once they get used to the workload. Lerner says that the PLC has created a universal grade contract in which students who do significantly better in the second semester of a class can get their previous semester’s letter grade bumped up accordingly.

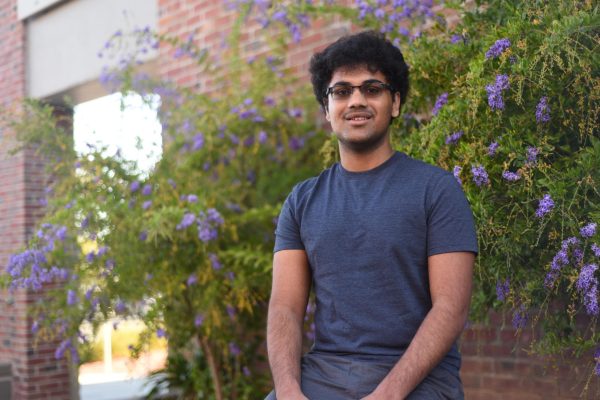

Similar to Lerner’s ideology that freshmen will adapt to coursework throughout the school year, senior Ganesh Batchu believes that students can adapt to a steady increase in workload throughout their high school careers. Batchu says for certain classes, it may take a couple weeks for a student to adjust, but over the years, Batchu has noticed that teachers tend to be more lax towards upperclassmen students as they have already solidified basic high school study habits into their lives.

“Senior teachers tend to be a lot less strict than sophomore or freshman teachers because they expect those students to be capable of more,” Batchu said. “Overall, I would say the average Monta Vista teacher would tend to be understanding. I think teachers will round your grade up if they know that you’ve been working hard in class and are diligent with your work. Those teachers, I can respect, because their decisions are based on the fact that you’ve worked hard the past year.”

Batchu’s experience with his teachers is reflected in World History and A.P. Macroeconomics teacher Scott Victorine’s teaching philosophy. Victorine has relied on the personal experience he has gained over the years to determine whether or not individual students are qualified for certain grading practices, such as retakes.

“There has been a real dedicated effort by the teachers in this department and the department itself to have fair and flexible grading practices across the board, regardless of whether it’s an AP class or a regular class,” Victorine said. “However, in certain situations, it is the effort that a student puts in and the attitude they bring to class. Are they really close to the grade? And if so, did they really put in the effort there throughout the semester?”

Rather than relying on intuition and experience like Victorine, Lerner prefers to stick to a standard rule-based grading system set at the beginning of the year. Through her syllabus and repeated testing practices, Lerner sets an early expectation for freshmen that they have to consistently work hard throughout the semester.

“I start with smaller assessments and then build to the bigger ones,” Lerner said. “So maybe they didn’t get it the first week, but after week two or week three, they should do better, and then they have a bigger assessment. And if that still doesn’t work, they have a retake. The idea is to recognize that different people take different amounts of time to learn, and to keep rewarding that, rather than having some big, high stakes test at the beginning because then they will feel like they have to give up completely.”

Batchu says that certain teacher-specific policies can still affect individual students’ motivation and study habits significantly even after having years to adjust to a high school level workload. Batchu noticed that getting demotivated by the amount of coursework put on him by certain teachers has become fuel for his motivation as he has gotten older.

“The harder and stricter policies demotivated me,” Batchu said. “I also think on the flip side, the harder the courses are, the more motivated I’ll be to work so it balances out. If I ever get a bad test grade, then that will motivate me.”

Many teachers at MVHS standardize their grading practices within their departments for the sake of fairness. Furthermore, whenever Victorine is making a new policy for his class, he views the policy through the perspective of his students in order to determine if it is just.

“I have a child of my own now and she’s 4 years old,” Victorine said. “When she is in high school, I ask myself, ‘What would I want it to be like for her? What would I want it to look like for her? Would it be good enough for my kid?’”

Although Lerner and Victorine teach different subjects, they both give many opportunities to their students to make up for their grades. Victorine allows his students to retake his tests up to 100% and allows students to submit late work for no penalty until the end of the current unit. On the other hand, Lerner allows retakes for tests up to 80% and may give the class up to 1% extra credit each semester.

While Lerner knows that some of her students may be upset by her grading policies, she is firm in her belief that students should be able to get the grade they want by the end of the year if they are able to take advantage of the opportunities given to them.

“Ultimately, you do need to know the material,” Lerner said. “There’s no magic I’m going to sprinkle on your grade if you don’t know the material. In the end, that’s the goal of the course, so at some point, if you don’t know the material, then your grades are not going to be so good. But the idea is to give you as many opportunities as possible to show you know the material.”