Chinese teacher Zoey Liu usually keeps in touch with her friends and family, regardless of where they live, through Wechat — a popular messaging app commonly used in East and Southeast Asia. While most of her conversations over Wechat do not usually concern politics, Liu’s friend recently messaged her an article with a concerning headline — “Elon Musk will become the next president of the U.S.” As an experienced user of Wechat, Liu was able to recognize the message as just another case of false news circulating on the platform. However, she acknowledges that others, especially those whose first language isn’t English, could easily fall for such cases of clickbait.

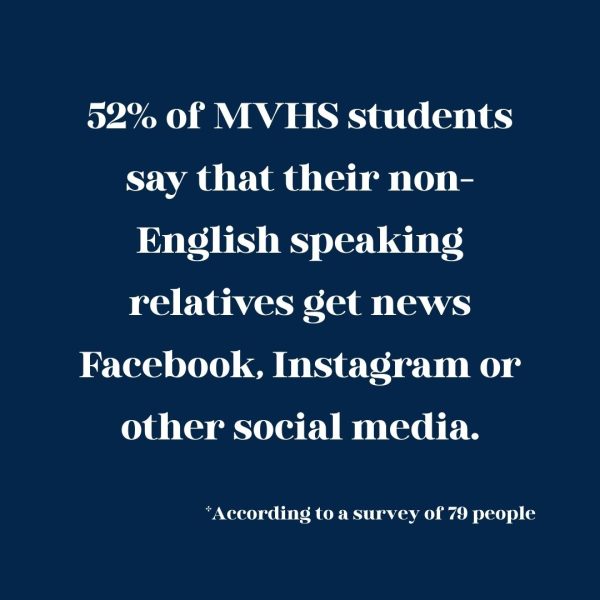

In immigrant communities across the U.S., where almost 66 million people speak languages other than English at home, platforms like Whatsapp and Facebook are commonly used for news consumption — 29% of adults using Whatsapp and 68% use Facebook, both of which are notorious for misinformation. By using online messaging and social media platforms as a source of news, the users were unwittingly surrounded by a relentless amount of misinformation. During the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic, Facebook became a center of fake news regarding the virus, misinformed posts garnering around 117 million views — many of the posts markedly racist and contributing to the rise of anti-Asian discrimination that occurred during and after the pandemic. Although Facebook began implementing a fact-checking system, a study by Avaaz found that 51% of non-English misinformed content still did not have a warning label compared to only 29% of English content.

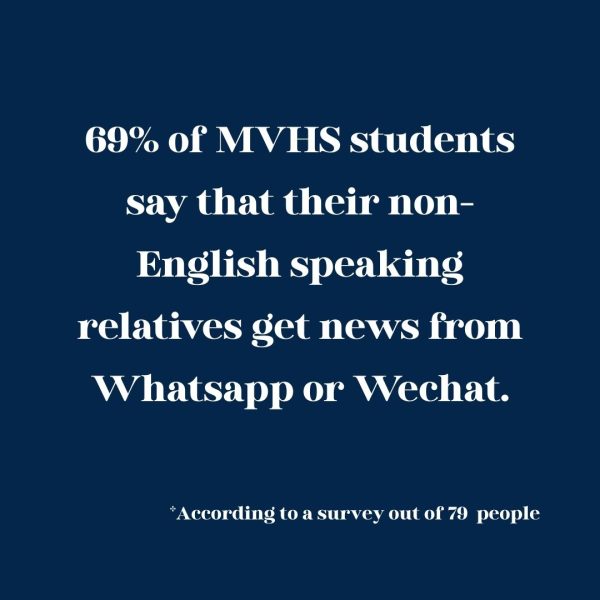

While encountering misinformation is an experience that many English-speaking Americans face, this issue presents a greater challenge for non-English speakers in the U.S. who aren’t able to differentiate between real and fake news due to the language barrier. Oftentimes, there is a lack of reliable information on healthcare, voting and other topics of high importance for non-English speaking consumers due to the lack of content in other languages. As a result, the landscape of information for non-English speakers is barren, drawing them to alternative sources like Wechat, Whatsapp or other forms of social media, where the cycle of misinformation first begins.

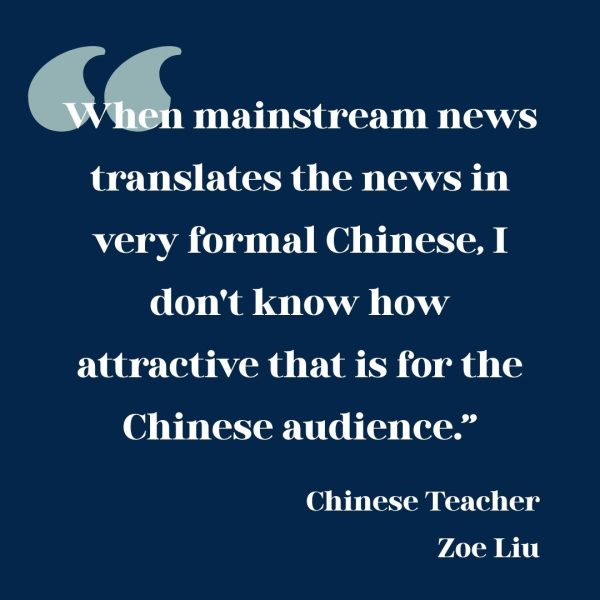

In addition to messaging apps, many news outlets make an attempt to translate news for non-English speakers on popular social media platforms, such as Instagram and Facebook. However, misinformation here is further exacerbated due to the lack of fact-checking done for the translated content, something individuals who don’t have a journalistic responsibility to uphold often neglect to do. Liu notes that translated news also tends to be unattractive for their target audience, further worsening the issue.

“When mainstream news translates the news in very formal Chinese, I don’t know how attractive that is for the Chinese audience,” Liu said. “Compared to someone publishing something eye-catching on Wechat like ‘Elon Musk is going to become the next president,’ which is in very simple terms, mainstream media outlets don’t stand as an option for Chinese users. ”

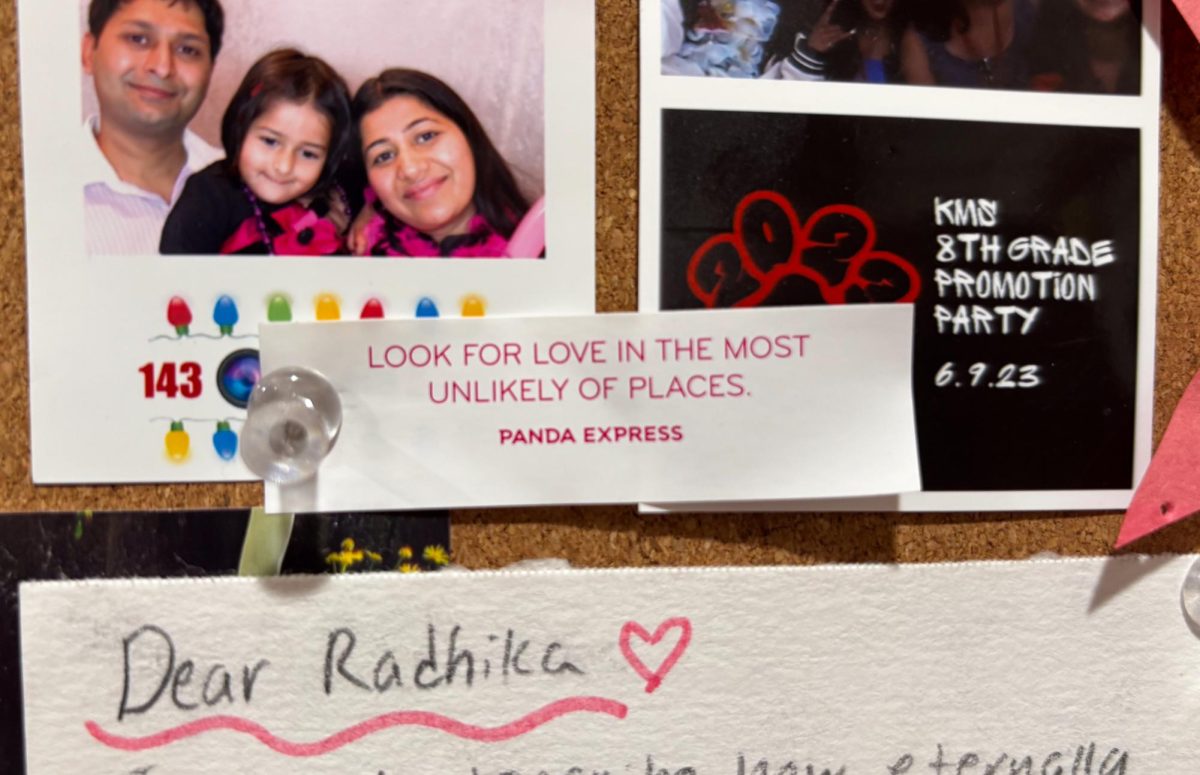

Since there is a lack of a personal connection in traditional media, non-English speakers are more likely to rely on the information passed through messaging chains with family members or word-of-mouth from friends, especially in communities where word-of-mouth is prominent and valued.

It’s important that we demand more from mainstream media outlets by voicing our concerns and opinions. Whether or not they are based in the U.S., any media outlet that declares themselves a source of information for global news has the responsibility of providing information to people of all demographics. The best step that news outlets can take is to use journalists that are based in other countries and have them produce news in their respective languages so that there is more holistic coverage of global news.

In addition, major social media platforms, such as Facebook, where posts are publicly shared, need to implement stricter fact-checking tools by not just relying on artificial intelligence, but also assigning experienced translators who monitor these platforms.

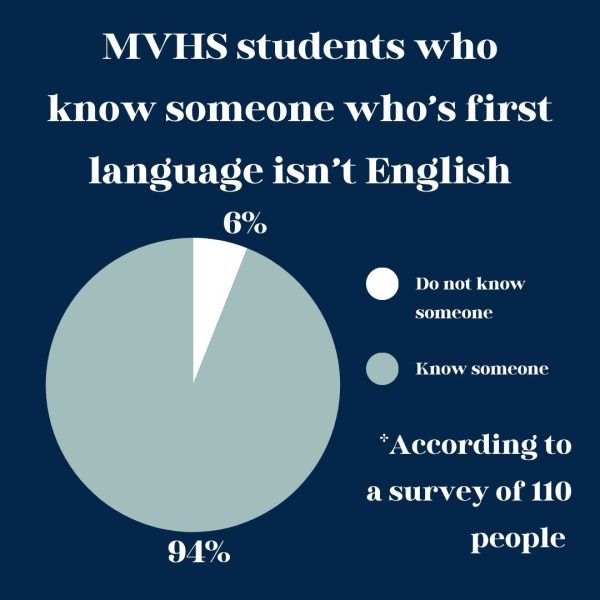

While the issue can be solved by broader big-world solutions, there is also a role students can play in fixing the issue within their own community. For MVHS students, living in an ethnically and culturally diverse community, this is a problem that their parents, grandparents, friends, neighbors or even themselves have likely experienced—with over 93% out of 110 Monta Vista students reporting that they know someone whose first language isn’t English. However, the relevancy of this issue doesn’t just end with how it affects us and our families — it’s up to the newer generation, especially MVHS students who are children of immigrants, to reduce the amount of misinformation in the coming years.

Above all, the responsibility of ensuring that sources are reliable and that those around us do not fall prey to misinformation in our community, falls on our shoulders, as MVHS students and as the technologically adept generation. In addition to refusing to participate in the cycle of misinformation on online platforms, it is vital that we also continue to keep our non-English speaking family and friends educated about the reality of the information that is spread in their community by giving them feasible strategies that they can use to verify their sources. By taking proactive actions such as initiating conversations about verifying our information, finding sources that we can count on to be reliable, and reaching out to find news outside of just group chats, we help prevent our loved ones from becoming victims of fake news. When we don’t do our best to guide and assist the people close to us, we end up inadvertently feeding into the cycle of misinformation as well — instead, we can help our community from blindly following others and getting trapped in the web of lies.