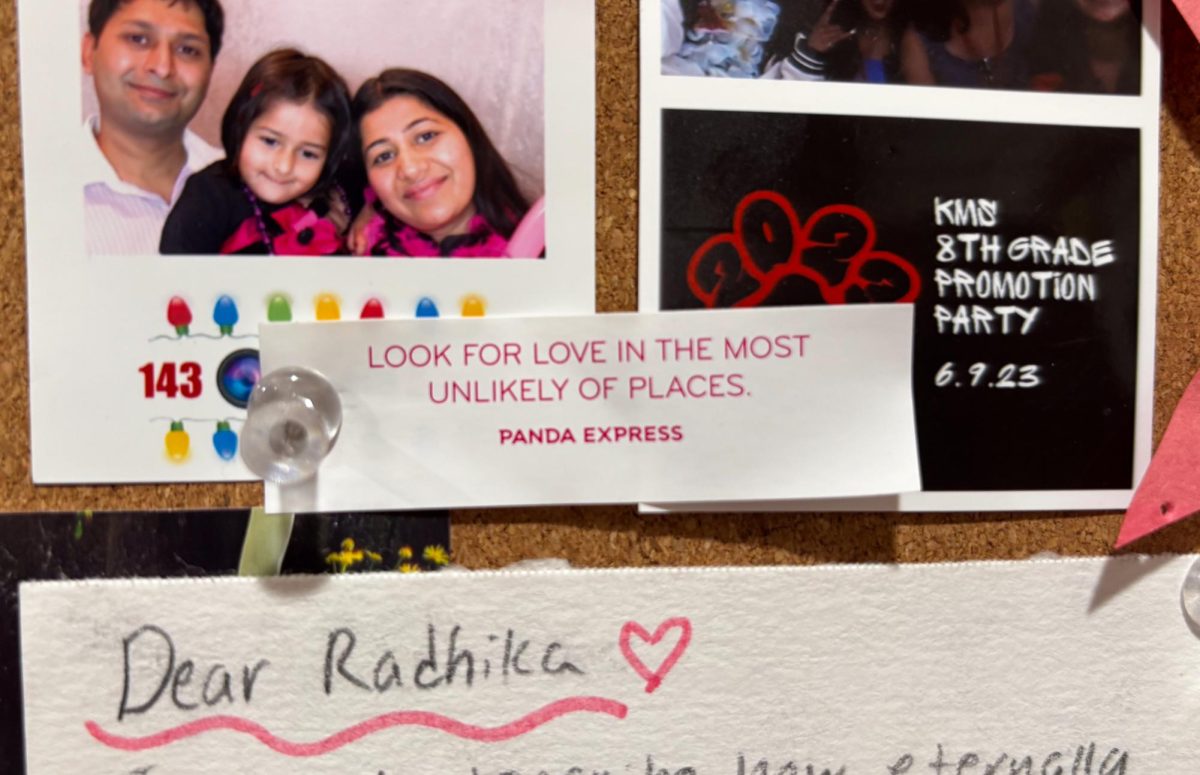

When my grandmother lived with us, the dinner table routine was a methodical, well-rehearsed custom in my family. The meal would start with a couple bites and a conversation about how our days went. Then, we went around the table asking my grandmother questions: “What did you eat today?” “Which country are you in?” “Do you remember going on that walk? Drinking your tea?” These questions, attempts at getting my grandmother to recall her day from memory, were met with a shake of her head or a shrug of her shoulders. My grandmother was diagnosed with dementia in 2023. She struggles to remember events that happened days, hours or even minutes before — things like how to make tea or what she did earlier in the day vanish from her memory. Despite these questions being met with uncertainty, we continued to ask them almost every night, simply to surround her with familiar information and hope that, over time, it jars her memories.

After we adopted our dinner routine, I would find myself reciting the dinner table questions on the way home from school, while brushing my teeth, or doing the dishes. I began to worry that my grandma’s memory loss was a permanent part of her, a stain that couldn’t be removed no matter how hard we tried to help. While my family initially found it challenging to adapt to her diagnosis, we were able to work through it and provide my grandmother with a solid foundation of support.

Before my grandmother’s diagnosis, I lived my life chasing a constant high. When I performed well on a test or in a speech tournament, a sense of relief came from that consuming feeling of accomplishment, one that blossomed in my chest and spread to the rest of my body. Instead of feeling pride, I felt like a weight was lifted off my shoulders, free from the stress I put on myself to do well. But instead of reveling in it, the anxiety of failing the next time quickly took over.

My life was built around these highs. I wanted everything else to go by quickly, blurring right in front of me, so I didn’t have to dwell on my losses. In my eyes, the quicker life went by, the easier it was to recover from failure.

My grandmother’s lifestyle is the complete opposite — because of her inability to comprehend complex things, she takes life slowly. One Saturday morning, my grandmother and I were going for a stroll around my neighborhood, one of my arms wrapped around her and the other clutching my phone tight, nervously refreshing my chemistry grade to see my latest exam score.

So preoccupied with my school life, I neglected to notice that my grandmother and I had stopped in the middle of the sidewalk, her attention focused on a ladybug that landed on her arm. I tried to shoo it off of her, but she moved her arm away from me, observing it with fascination. Slightly exasperated from our stoppage, I attempted to get us to continue moving by gently urging her forward, but she stayed in place.

“Look,” she said curiously.

Taking a deep breath, I wanted to reply that I had seen countless ladybugs before, but eager to get home and figuring that this would be the quickest way to continue moving, I complied. I watched as the insect crawled up her wrist and my grandmother turned her arm over to let it crawl on her hand. When I looked up, I saw my grandmother had the biggest smile on her face, eyes full of wonder — although I may have seen countless ladybugs before, this was practically her first time. Her unfiltered happiness made all of my school worries dissipate, and it made me grateful that I could share the moment with her.

We continued our walk, this time with her pointing at clouds and picturing them as animals, or pointing at different houses we walked by, commenting on their colors — cream, brown, and one even a vibrant blue. But the next time I looked over at my grandmother, she wasn’t looking at the houses or the clouds anymore: she was beaming at me. It hit me suddenly, that for the next 20 minutes, this moment would be her entire world. It was all she knew. To someone on the outside, we were just two people taking a walk, but to my grandmother, she was having the most fascinating day of her life. And then, I felt it. The feeling that blossomed in my chest, and slowly spread its way all throughout my body.

All my life, I chased a feeling I thought could only be found in the most grandiose and climactic of moments, but the same feeling could have been found in the folds of everyday life all along. My grandmother’s joy in the most mundane things made me question — why was I stuck refreshing a page, anxiously waiting for my next top-of-the-world moment, neglecting the one happening right in front of me?

Since then, I have begun to live my life as my grandmother does, finding joy in everyday moments. Instead of only feeling that high from my biggest accomplishments such as tests or tournaments, I notice it everywhere, every day. When I share oranges with her, I take a moment to appreciate the smell of the peels on my hands: fresh and sweet. And despite her going back to live in India, she is with me everywhere I go. I pay closer attention to my route to school, noticing minuscule things — the sound of construction, the bumper stickers in traffic, the smells wafting from apartment complexes.

My grandmother’s fascination with the ordinary taught me to revel in it, to savor every second whether it be the uphill, the downhill or the plateaus we all experience as people. In these fast-paced years of high school, we often forget that our lives don’t have to be condensed down to extensive lists of school, work and extracurricular milestones. We tend to narrow our life to successes and chase the next big thing, forgetting how much is in front of us that can bring us just as much fulfillment, if only we grow to appreciate it. After all, life is an accumulation of small, ordinary things that make it worth living — all we have to do is look for them.