Thunderous crackles reverberate through the air, piercing the curtain of smoke that veils firefighter engineer Ruri Kobayakawa. Her boots crunch on shards of glass as she hoists her fire axe and shuffles to face her next target. Despite wearing over 50 pounds of equipment, Ruri shatters the entire balcony window in one blow. Her task is essential; the windows must be broken in order for the water from the hose lines to reach the inside of the burning 72,000-square-foot building.

While Ruri understands the gravity of her job, she still enjoys it, specifically recalling “how amazing” her career was to include breaking windows. Yet, 15 years ago as a freshman at MVHS, the life of a firefighter at the Santa Clara County Fire Department was not what Ruri imagined for herself.

“The environment of MVHS is unique in that realm of its high stress on grades,” Ruri said. “Everyone’s on each other about it — you get a B and you feel like you have to hide it from the rest of the class. That definitely stressed me out because I wanted to feel accepted in what I chose as a career. It wasn’t until I got to college and got away from that that I thought on my own and asked myself, ‘What do I truly want out of a career?’”

Ruri’s parents expected her to find a career in tech, like most of her peers from MVHS. However, once her dad saw how fulfilled she was after she attended South Bay Fire Academy, Ruri had his full support in pursuing firefighting. When considering careers, Ruri thought about who impacted her life when she was growing up.

“My home environment wasn’t the best in high school,” Ruri said. “I felt alone because when everyone’s going through stuff, it’s hard for anyone to focus on each other. Anytime a fire engine or an ambulance drove by, I was the kid that was waving at it. That simple action of firefighters waving back, you don’t think much of it being on this side of it. You wave back. But for me as a kid, in that time where I felt super alone and unseen, that simple action helped me feel like people still do see me, people still care that I’m around.”

In retrospect, Ruri’s older sister Melissa Kobayakawa believes Ruri’s choice to become a firefighter suits her personality. Ruri was the sister who was always “throwing toys everywhere,” while Melissa was the sister who was “picking them up and putting them back,” balancing each other out.

“Even though we’re sisters, we are so different in so many ways,” Melissa said. “I could never do what she does. She’s so fit, she’s a go-getter and is just willing to put her life on the line. Even as kids, when she would play tennis, she would dive for the ball and scratch her knees and elbows. She would sacrifice her body for the tennis ball. And I would not try any of that. I was like, ‘She’s crazy.’”

Ruri enjoys the unpredictability of firefighting, appreciating how no two days of work are the same, and as a result, having to be constantly learning. While Ruri loves many parts of her job, she ultimately chose to be a firefighter out of her love of helping others and being involved in her community. But as a first responder, there are situations where, despite her and the crew’s best efforts, people pass away.

“You always ask yourself, ‘Could I have done more?’” Ruri said. “‘What if we got here earlier?’ But in most cases, we couldn’t have helped and we need to accept that as much as we wanted to help, sometimes that wasn’t a possibility. It’s hard to focus on the positive. It’s important to appreciate and remember the good calls where you make a difference to balance out the negative calls.”

Since taking on hard calls is a regular part of a firefighter’s job, Ruri’s department offers a multitude of programs and free therapy sessions for anyone who needs extra support. Firefighters learn to emotionally distance themselves from the scene while on call. Despite these attempts, Ruri says it is impossible to predict how a firefighter reacts on the scene, especially if they go on a call that reminds them of something from their personal life.

“Personally, I struggle with any calls relating to suicide because I battled with that through high school,” Ruri said. “Those are the calls where I’m like, ‘Oh god,’ remembering how I felt in those times when I was younger, and to understand how that person felt right before they decided to act is always rough for me, especially because I tend to be a pretty empathetic person so it’s harder for me to distance myself from those situations.”

In situations like those, Ruri and her crew also tend to rely on each other for support. As a result of spending two days together every week, she has come to see her crew as a second family. These close bonds she has forged are just another aspect Ruri loves about her department and job.

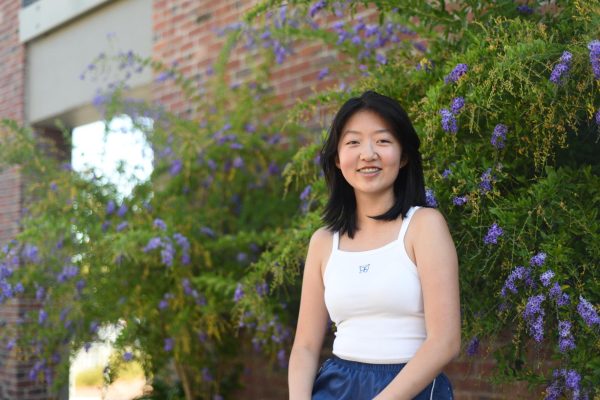

(Liz Liu)

Some of Ruri’s fondest memories of her job revolve around the time she’s spent with her crew answering calls. Her job as a firefighter includes much more than fighting fires; it’s anything from responding to highway accidents to helping an elderly couple with leaky pipes and other light-hearted calls: lost drones, cats stuck in trees and ducklings believed to have fallen down a storm drain. Ruri finds it important to hold those little memories dear: the moments spent giving stickers to awestruck kids, the laughter Ruri and her crew shared as she stood in a storm drain searching for ducklings, and much more.

Ruri’s close friend and fellow firefighter engineer at SCCD Katie Doherty feels similarly about the relationships she’s formed as a firefighter. However, she notes that it took her years to feel like she belonged in the fire service, having a sense of imposter syndrome. Ruri shares this sentiment. While undergoing firefighting training, she had trouble with the essential firefighter skill of throwing ladders, which sometimes weigh upwards of 60 pounds and are over 12 feet long, off her shoulder and against a building, and at times even believed it was impossible for her to do.

“I’ve seen a lot of females struggle through self-doubt,” Ruri said. “Being your worst critic sometimes doesn’t help you in the end. It’s great because it creates high standards for yourself, but it can also hinder you if you don’t believe you can do something. Another thing is we are built differently than the guys. A lot of us tend to be smaller. A lot of us don’t have the upper body strength that some of the guys do, and because of that, the way things are taught is usually based on how guys perform.”

While Doherty’s department is very accepting of women, she has noticed how firefighting seems to be more catered to men. For example, Doherty never received personal protective equipment that fit her until she was hired as a full-time firefighter; her protective clothing, pants, gloves and helmets were all oversized. She recognizes that the career still has room for improvement in terms of building a friendlier workplace. She recollected a medical call where her partner, an older paramedic, made a comment while they were out on a call.

“I was putting on a 12 lead: stickers on the chest to take pictures of the heart,” Doherty said. “He thought I had put one of the stickers on in the wrong position, and in front of everyone: my boss, the EMTs, the patient, and the patient’s family, he said, ‘Sweetheart, that’s not in the right spot,’ and pulled it off of his chest and looked at it and said, ‘Oh, no, wait, that’s fine.’ He would not have called a guy ‘sweetheart’ and it was not professional.”

However, Doherty believes having supportive colleagues really made a difference, and she counts herself lucky as she has mostly never been shown signs of overt sexism. When comments were made, Doherty said she had allies who spoke out for her. Ruri agrees that firefighting has its challenges, especially for women, the rewarding aspects of firefighting far outweigh anything else.

“Through this career, I’ve also seen how much women can push and how much they can accomplish,” Ruri said. “Especially when you get any woman to hit that point where she’s like, ‘I can break this boundary,’ there’s no stopping us. Sometimes, we’re just driven. We’re like, ‘This is going to get done.’ It’s been super inspiring to see that drive in a lot of people. And so even though there are challenges, you get to see all these people who are taking that as a challenge and being like, ‘I’m gonna push past that.’”

To encourage more youth to experiment with firefighting as a potential future career, Ruri is involved in weekend fire camps, where high schoolers can try different fire skills. Through her involvement in these programs, she’s learned about more fire service programs reaching out to women. Doherty remembers her first meeting with Ruri clearly— sizing Ruri up and underestimating her before being blown away by her abilities. She recalled being shocked at how well Ruri was able to keep up with the rest of the group. Also, although Doherty thought Ruri to be quiet and reserved, especially compared to other firefighters, she has since then watched Ruri grow into a confident person.

“It has been really awesome to see her just absolutely crush everything she does, especially in the fire service, and then go back and teach people skills,” Doherty said. “She works at our department’s truck company, so not only is she super strong, she’s a tiny lady. Truck companies are generally considered the giant strong guys that break s—, and she just f—— crushes it, and then she’ll go and teach people. It’s really cool to see her have a voice and be really amazing.”

Even outside of her job, Ruri prioritizes community involvement by teaching others, utilizing the skills she gained from teaching taekwondo as a black belt in high school. She now teaches at Blaze of Glory Fitness, the firefighter functional fitness trainer and mentorship program where she and Doherty first met, and teaches fire skills at the South Bay Fire Academy.

“When I’m standing by our engine or our truck, people will come up to me and ask me how the job is,” Ruri said. “I’ve had other girls come up to me and be like, ‘Wow, you’re a firefighter. Can we do it?’ I was like, ‘One hundred percent!’ I definitely enjoy being able to open that door for people to think about, that this is a career anyone can do. When joining the fire service, I wanted to challenge myself, even knowing it was a male-dominated career. I want to show people that anyone can do this job. As long as you want to do it, you have the drive to do it, you want to learn and you want to be able to help people, anyone can do it.”