The price of prescription medicine has long been a topic of political and social debate. In 2023 alone, the U.S. spent around $722 billion dollars on prescription medicines, or over $1,000 monthly per person without insurance coverage. This poses a significant inconvenience to many Americans, especially those struggling financially. Parvaneh Sanaeinourani, a district nurse for FUHSD, says that many variables may determine the cost of a particular medicine, especially its brand and its novelty.

In the past five years alone, prescription medicine costs have risen 22.2% with an average increase of 5% each year. Additionally, a 2023 poll found that 82% of Americans thought the price of prescription medicine was unreasonable. Sophomore Ruchika Varanasi, who uses prescribed epinephrine pens (EpiPens) for emergencies related to her dairy, nut and egg allergies, says that these increasing prices limit access to prescription medication, especially for people with lower incomes.

“I think the price changes could be because of inflation for sure, and also the need for people to access these medicines,” Varanasi said. “Drug companies see high demand, and they think, ‘Oh, I should set higher prices because of higher demand.’ I’m lucky enough that I can get access to these medications and be able to pay for them, but some people have allergies or conditions and don’t have enough money to cover these, and it can be life-threatening for them if they don’t have access to medication.”

While this is a serious issue, there are systems in place to assist people who have trouble affording prescription medicine. According to Sanaeinourani, you can reach out to drug companies, doctor’s offices or support groups, or ask for any alternative medications. However, MVHS math teacher Katie Collins says that this isn’t an option for people reliant on a prescription drug without alternatives. She mentions that the prices of prescription medicine in the U.S. have driven people to look elsewhere, like Canadian or European pharmacies.

While this is a serious issue, there are systems in place to assist people who have trouble affording prescription medicine. According to Sanaeinourani, you can reach out to drug companies, doctor’s offices or support groups, or ask for any alternative medications. However, MVHS math teacher Katie Collins says that this isn’t an option for people reliant on a prescription drug without alternatives. She mentions that the prices of prescription medicine in the U.S. have driven people to look elsewhere, like Canadian or European pharmacies.

“You don’t always necessarily know what you’re getting is pure if you’re buying from some random place,” Collins said. “But there’s a lot of overseas pharmacies where you can send your prescription in, and then you can get cheaper drugs. In other countries, instead of letting pharmaceutical companies dictate prices and rake people over the coals, they’re putting more stop gaps for that kind of behavior, yet the American pharmaceutical drug industry can’t do that.”

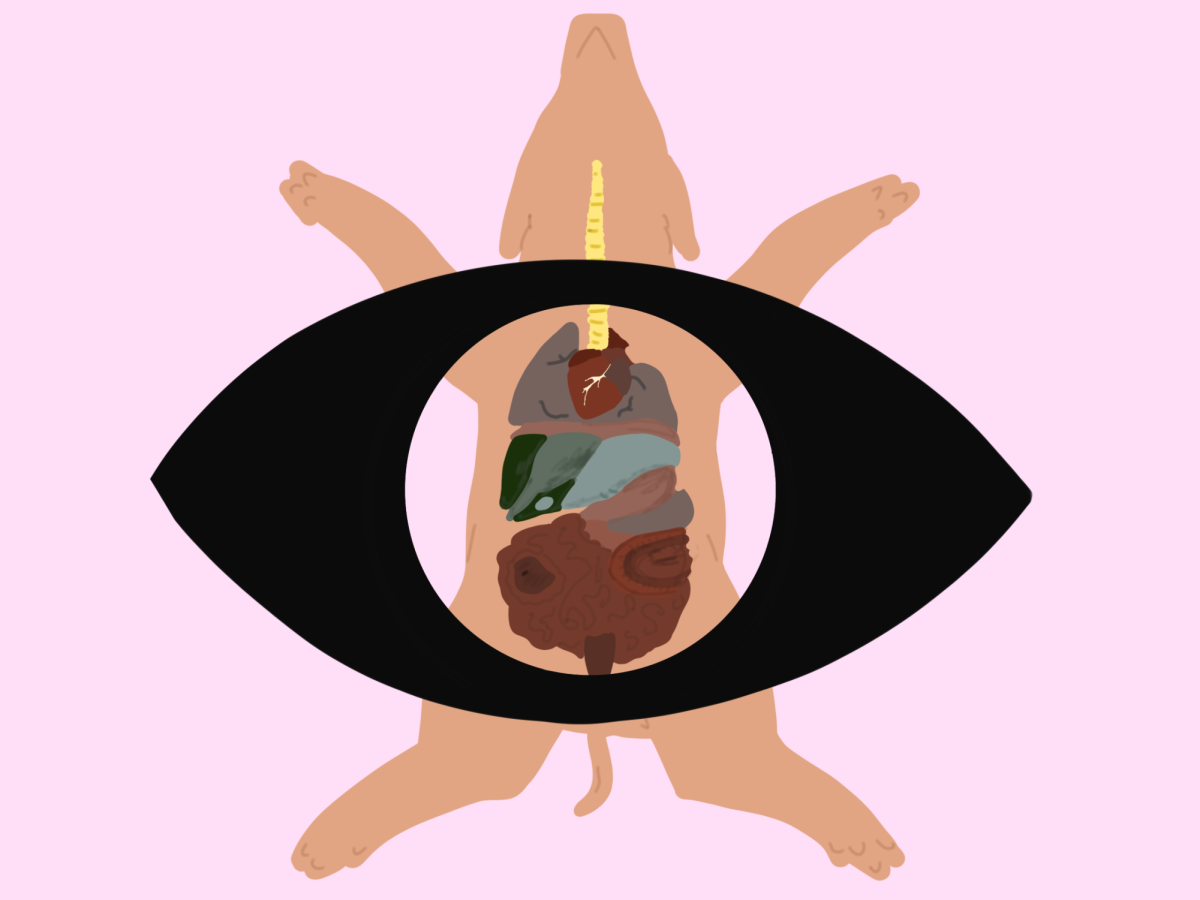

Since she started taking prescription medicine at 37 years old, Collins’ list of prescriptions has grown to include immune globulins, mestinon, antibiotics and antifungals for her conditions, which include autonomic neuropathy, autoimmune autonomic neuropathy, dermatomyositis and her orthostatic problems. Over the years, she’s had to learn to adapt the way she goes about taking prescription medications due to her experiences with medical professionals.

“[Doctors] will just throw medication at you based on a symptom that could show up in 100 different diseases,” Collins said. “I was in the hospital a couple of weeks ago, and a doctor tried to give me a medication that would have been completely contraindicated for my heart and nervous system conditions, and they just wrote down that I was non-compliant with their prescription. They had no business giving me that medicine without consulting a knowledgeable cardiologist and neurologist. So I have to educate myself, and I think most people learn that the hard way.”

According to Collins, even though she often spends weeks in severe pain due to the conditions she experiences and the misinformed medical staff, she doesn’t believe she has any other options due to the cost.

“The reality is, if I were to go on Medicaid or disability, I’m going to be really screwed because of the things that I would have to pay for,” Collins said. “It would be financially untenable, and we have already moved out of our house to pay for healthcare and we live with my parents. We’re selling off some of our other assets, like a vehicle. Going on Medicaid would increase an already very high cost for us. It’s not sustainable.”

Collins and Varanasi both acknowledge that FUHSD provides resources for people struggling to pay for their prescription medicine through support groups where students or teachers can discuss their experiences. According to Sanaeinourani, MVHS also offers a support group for students without insurance which helps connect them with Medi-Cal, allowing access to a variety of medications.

Although Collins praises FUHSD’s health care plan for teachers, citing it as better than previous healthcare plans under other employers, she mentions an experience where the school decided to reinterpret the health care plan. She was forced to hire a private advocate to fight with the insurance company herself for coverage of her medications.

From this experience, Collins highlights the importance of banding together and forming supportive communities to combat the pharmaceutical companies driving the prices up. Varanasi agrees, discussing the need for people to band together to collectively achieve their goals.

“Enough people talking about the costs will help make them less expensive,” Varanasi said. “Even talking to these insurance companies and telling them, ‘Hey, this is a life or death matter, some people need these medications to survive, and if they don’t have them, then you’re losing people. You don’t want to do it for your own profit. You want to do it for the good of people.’”

Collins emphasizes the human aspect of Varanasi’s point. According to her, pharmaceutical companies need to do better, and take people’s life-or-death needs more seriously.

“The behavior of pharmaceuticals is unconscionable,” Collins said. “Some of that has to do with how we allow these big businesses to run amok and do whatever they want. If people need medication, they need access to it. I’m keeping my job so I still have health care, but a lot of people don’t, and cannot afford some of these medications. When people can’t afford to get their insulin, they could die. People have a right to life, and if life means you need insulin — to keep people from getting it because they can’t afford it, that is criminal.”