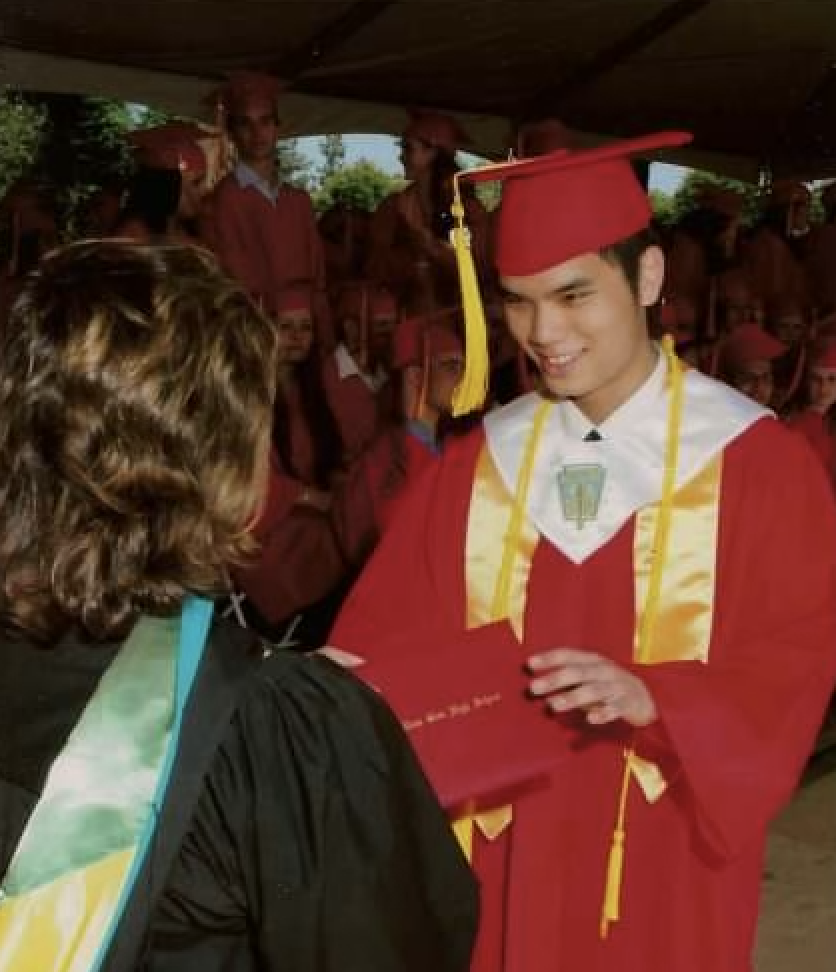

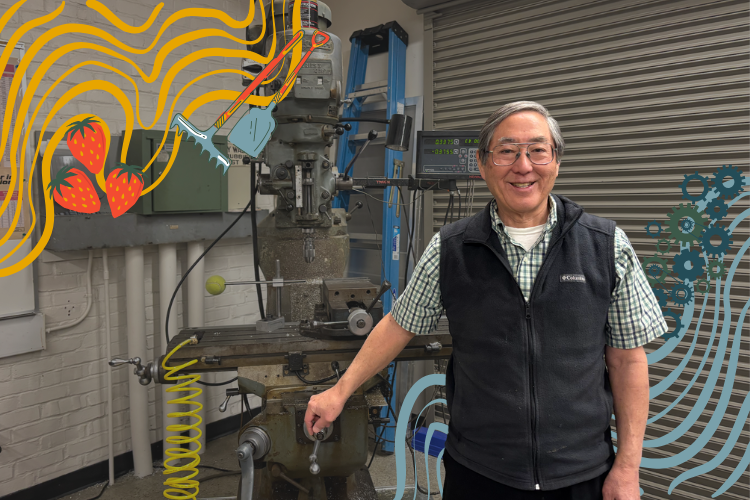

When he was a sophomore in high school, math teacher Josh Kuo’s family immigrated from Taiwan to the Bay Area. The transition was nerve-wracking as he felt he lacked familiarity with American culture and the English language. Kuo recalls watching as his career aspirations and love for learning became replaced by the challenges of a language barrier, posing strains on his academics. Furthermore, the language barrier also prevented him from expressing his personality, causing him to struggle socially.

“It crippled my ability to learn,” Kuo said. “After I got here, I stopped liking reading because I didn’t feel like I could do it or enjoy it. In Taiwan, I was more of an outgoing guy, but once I got here, it became hard to get my personality across. A lot of times, it handicapped my ability to make friends. I eventually had to overcome and accept myself for who I was, and be more assertive, be more confident about myself, which is something I have to kind of slowly improve.”

Similarly, when junior

Maryam Abdurahimova immigrated to America from Azerbaijan in sixth grade, the difficulties of adjusting to the English language were compounded by another obstacle — the sparsity of the Azeri language in the Bay Area prevented her from finding an immediate community of support. However, Abdurahimova says her curious and expressive personality allowed her to build relationships and community.

“I found it exciting, because [it was] something new and I got to experience new cultures,” Abdurahimova said. “When I came to America, I had to be really, really open to other people since my English was really bad. I couldn’t understand anything, so I just spoke with whatever I could. I spoke a lot with my hands, I used to do a lot of hand movements to communicate. That really helped me because a lot of people approached me and wanted to be friends with me. So I think if someone is more closed off, it would have been way harder for them to even learn English as well.”

While adapting to his new life in America, Kuo found himself increasingly drawn to math as it did not require advanced English and was essentially the same around the world. Focusing on math allowed him to fill in gaps in his learning and excel at the subject, opening opportunities for him that were initially barred by a language barrier.

Like Kuo, when sophomore Xiangning He moved from China to America during elementary school, academics struck her as the most difficult part of adjusting. On top of more difficult academics due to learning in English rather than Chinese, the American school system posed drastic differences from what He was accustomed to. For example, she was not used to changing teachers so often or the flexibility in the amount of courses taken.

“It’s a totally different education system,” He said. “The hardest part for me is the science classes because there’s a lot of difficult vocabulary for specific words.”

Kuo found that his only sanctuary during the beginning of his high school experience was spending lunch periods in his Physics teacher’s empty classroom. Reflecting on that time, Kuo feels a designated space for him to go for community would have helped him assimilate socially. Now, he opens his classroom as a welcoming space for Mandarin-speaking students and engages with the students regularly.

“A lot of students probably just want to ask for help from someone they know for sure they can understand and someone that they feel they can talk to,” Kuo said. “A lot of times, students that don’t speak English well feel anxious to talk to teachers, especially outside of class time. And also a lot of their friends are probably here, so they say if they’re comfortable, then that means I’m not that scary. And once they get their problem solved once, then they feel more confident in asking me again.”

While He initially had trouble getting accustomed to the culture of America and the differences between the American and Chinese schooling system, making friends proved to be less of a challenge, due to the prevalence of Mandarin-speaking students at MVHS who helped her acclimate.

“I was kind of surprised that there are so many Asians in this area since I was in a U.S. middle school,” He said. “Here, the diversity is greater. When I first came to MVHS, I felt like, ‘Wow, there are so many Asians.’”

While Kuo’s community reaches many Mandarin-speaking students, students like Abdurahimova whose first language is rarely spoken on campus aren’t able to rely on these spaces. As a result, Abdurahimova has become more proactive in welcoming foreign students and helping them through similar obstacles she faced.

“I can understand that they’re struggling, especially in high school,” Abdurahimova said. “I know some people who came here in 11th grade, which is the hardest, so I try to help them a lot. If they have a problem, if they can’t solve something, then I try to help them.”

Abdurahimova echoes Kuo’s sentiment, saying that seeking out a community on her own was crucial to adjusting to the new environment, citing her current friend group as her community. While not having one’s language and culture represented on campus can pose discomfort, Abdurahimova sees the period of branching out as beneficial.

“I’m kind of glad because if there was one person that spoke my language, I feel like I would have been more attached to them and not try to break out of my shell,” Abdurahimova said. “I think I just learned that, whatever happens, you need to be open and make sure that people understand that you want to learn to get ahead.”