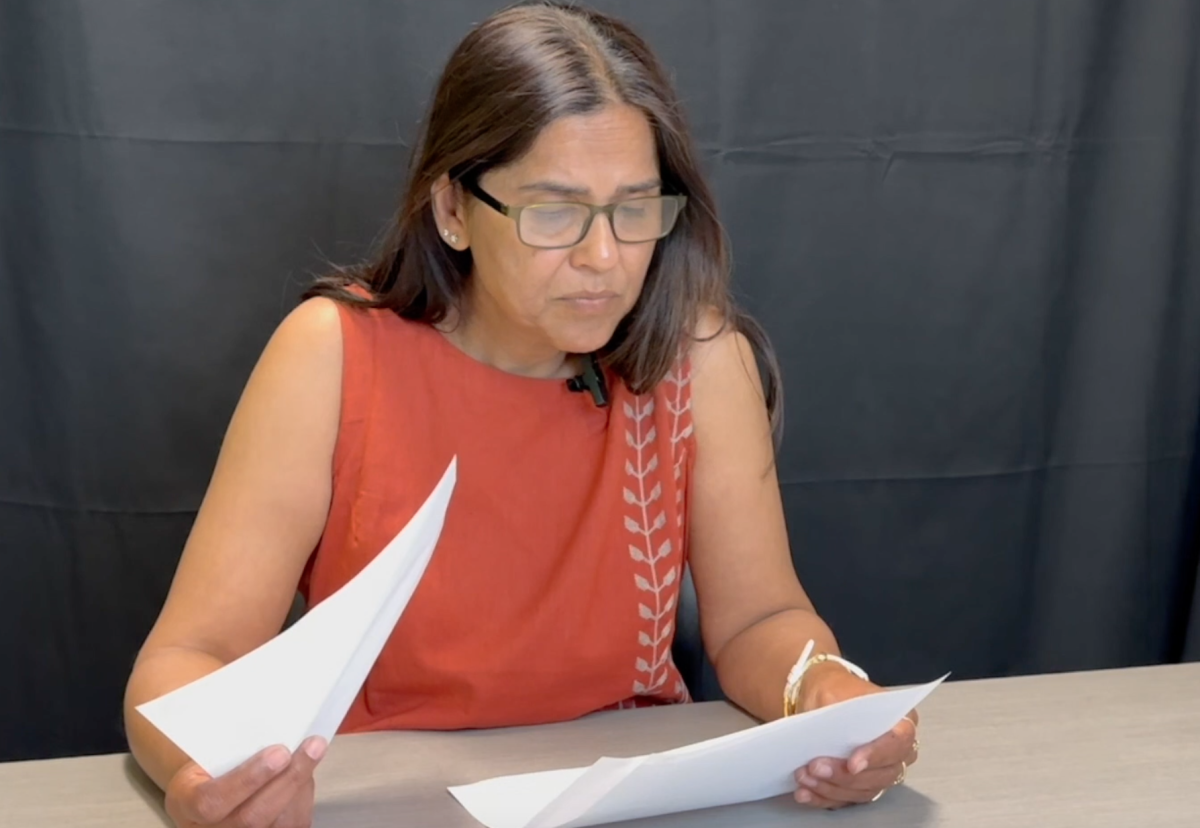

Now presenting… ‘A Bill to Extend Paid Maternity Leave.’ May the negation please speak?

I didn’t want to be there. I was forced to refute (or in debate jargon, negate) this bill. Yet, I still stumbled my way onto the stage and stood at the podium, trying to pacify my trembling hands. My notes, a chaotic mess, betrayed me, and I awkwardly swayed from side-to-side, shunned by the gaze of everyone in the room. Then the crossfire questions came.

Almost all other developed countries have implemented paid maternity leave and agreed on its importance. Why can’t we do it here?

I didn’t say a word.

That was my first debate tournament. I started debate after my fifth-grade teacher promised it would be a fitting intellectual challenge. Instead of bullying my classmates to use purple glitter on the history project, I thought maybe I could attack some real-world issues using my words.

I imagined a straightforward exchange of logic and evidence, and I was taught that it was all for one goal: the ballot which contained the judge’s decision. The coveted “W,” or win, could only be obtained by unveiling what was true and what was false (this I knew from my first tournament in which I clearly was in the wrong). After all, each debate topic began with “Resolved:” for a reason. My job as a debater was to bring us all to a firm, universal conclusion.

It was with this belief that I rode my way through the season, racking up wins and basic intuition of what was true and what was false. Soon, I found myself debating in the Harvard Invitational (granted, it was just middle schoolers chattering over Zoom). Choosing the negative side each time, my partner and I made our way through elimination rounds, making our case about the harms of African urbanization — pollution, disease and dangerous sand mafias.

But it was in the semifinals that we finally lost. It was to a new argument that we’d never heard before: how urbanization discouraged the practice of female genital mutilation, an illegal, harmful practice that involves the alteration or injury to female genital organs for non-medical reasons. And for all the numbers I recited about millions of people breathing toxic fumes and organized crime costing millions of dollars, for the first time, I saw that there were stories behind what we were arguing about. I had never seen the faces behind the arguments we passionately defended, and now, the cries of gender discrimination and human rights abuses echoed in the round. These were real experiences behind each path to the ballot. Maybe issues were more than just true and false.

I ended the round not wanting to argue on the negative anymore.

Entering MVHS, I quickly realized that high school debate was the real deal. So long were the days of trying to replicate the personas of MLK or Churchill with eloquent speech. The true competitiveness came on the national circuit, where teams “spread” (speed read) arguments as fast as possible and search for ways to link how even wayside issues, like expanding organic agriculture, would end in nuclear catastrophe. The more you said and the bigger the impact, the better.

And yes, this style of debate was (and still is) exciting. There is no thrill comparable to hearing that you won a round after arguing that a government shutdown is going to lead to tit-for-tat cyberattacks that cause extinction. But I was left with more questions than answers after so many rounds. The more extrapolated logical chains I read and heard, the more I began to see my idea of truth fade away. Was Turkey’s NATO membership going to help Ukraine or weaken the West? Were labor unions ushering in a worldwide recession or preventing millions of workers from entering poverty? The more I debated, the more that arguments clashed, sometimes flying past each other in a sea of ambiguity that only seemed to be resolved performatively. I couldn’t help but wish that I was back at my first tournament. Back when things were just simpler, and I could defend my positions believing that I knew the in-and-out truths of the topic.

I thought about this sitting outside a lecture hall at the University of Kentucky, having just debated terribly at the national Tournament of Champions. Mentally, I found myself standing at the last barrier of knowledge, staring at a myriad of contradictions. Six years. Six years of debating and trying to resolve issues, but the truth was, I couldn’t resolve anything. I asked myself if I was going to affirm or negate. I held myself up against the wall trying to figure out my genuine stance on the topic. But I couldn’t find an answer.

Then I thought back to my first tournament and replayed the scene in my head… Why can’t we do it here? And although years ago I never had an answer to that question, years of argumentation naturally guided a response that flowed through my head, bringing up Statista data from the abandoned corners of the internet and a mishmash of warrants to address the question. I didn’t know what to believe.

The value of debate was never to answer any questions, but rather to discover them.

After spending so much time debating, trying to find out what was true and false, trying to figure out the logic of how the world worked, I’ve realized that the world’s issues can’t all be packaged into clean-cut, black or white narratives, even though that’s the reason I joined debate in the first place. Behind each simple “W” or “L” lies complexity — the complexity of experience that demolishes the idea of a binary truth, urging me to be open-minded in the face of humanity’s unanswered questions. The value of debate was never to answer any questions, but rather to discover them. It was fitting that at the Arizona State Invitational this year, the argument that my team lost to was one telling us to abandon our fixation on answers and learn to embrace chaos.

Last month, when debating the most recent topic of “Should the U.S. ban single-use plastics?” I encountered coaches, parents, scientists and legal experts all sharing their viewpoints. I didn’t argue. I listened, and a flurry of questions unfolded from economic effects to social justice implications. Even though I had no answers, the richness of the lived experiences behind each personal argument resonated, as if embracing this complexity was a form of learning and realizing that there was no predetermined “W” or “L.” There was just me, a vessel of open thought. I walked away from the topic feeling like I had learned a lesson more valuable than any ballot.

While this is the last thing you’d expect a debater to say, there’s a beauty in uncertainty. Maybe the nature of life is that some questions defy tidy resolutions, as much as we want to believe otherwise. And paradoxically, some of the most meaningful answers are found within the questions we carry with us.

Some things can remain unresolved after all.