When sophomore Jivika Gulrajani first watched a TikTok announcing Melanie Martinez’s new perfume, she recalls being so shocked at the price that she dropped her phone. Gulrajani has enjoyed listening to Martinez’s music, especially due to their use of metaphor and their ability to explore taboo topics. While she still admires that aspect of their work, the presentation of the perfume brought doubts to her mind — to her, the $275 price tag is emblematic of a creator who doesn’t care about their fans.

“When you brand yourself as somebody who cares about their fans and somebody who’s economical and genuine towards the people they care about, but then you do something like this, it shows that all of that is fake,” Gulrajani said. “It shows you didn’t mean any of that.”

Martinez found success in the alternative pop genre but is best known for their ambitious use of aesthetics in their albums. Most recently, the album “Portals” reinvents the character, with Martinez being reborn into a pink fairy creature with four eyes.

The elaborate storytelling has been a strong draw for fans like Gulrajani, who connect with the immersive worldbuilding. Their merch adds an extra layer to each album’s theme, where products from different periods of their career have a distinct look to them. As Martinez claims, this newest perfume is an extension of their artistic vision, with the “Portals” perfume featuring a 1-foot tall statue of the fairy creature’s head, alongside four element-themed scents, totaling 60 milliliters.

Sophomore Lauren Moore likes to test and buy fragrances and also listens to Martinez. However, she discovered Martinez’s music after the “Crybaby” perfume stopped being produced. Moore found Martinez’s perfume through TikTok, and while she would be interested in trying the “Portals” scents, she says the price is too high.

“I don’t tend to splurge a lot of money on one perfume because I get tired of the scent,” Moore said. “Plus, it’s too expensive. Even some of my most expensive perfumes don’t touch $200, so I can’t imagine spending that much on this fragrance.”

Gulrajani agrees that the price came as a shock, especially because it differs from the pricing of previous perfumes they have sold. Martinez’s other perfume release, themed around the “Crybaby” album, was much less expensive, selling for $50 for 75 milliliters. Gulranjani believes the stark difference in cost is what makes many fans wary of a product disproportionate to its price.

“From what I know, their merch is very economical,” Gulrajani said. “It tends to be not cheap, but not expensive either. But then this new perfume was extremely expensive. They explained that the reason their perfume was that expensive was because it channels an inner spirit in your body, but I think that’s them saying that to excuse the price.”

Martinez has defended the price by tying it to their artistic vision, saying that they do not “make millions,” often sacrificing profit for the art they want to create. For example, the “K-12” film, which cost $5-6 million to produce, was released for free on YouTube. However, Gulrajani disagrees with that perspective, saying that the prohibitive prices go against the purpose of art in the first place.

“I don’t think it’s well spent at all, even if it’s a display of artistic vision,” Gulrajani said. “The whole point of art is to share it, but most of their fans can’t afford an expensive perfume, so to say that it’s for their artistic vision, why wouldn’t you make it more affordable for all of your fans to experience the very art that you’ve created?”

In Gulrajani’s view, it’s a problem that goes beyond one artist. The obligation to meet the audience’s expectations can often come into conflict with the artist’s desire to fulfill their own visions, especially when money is involved. But to her, it also comes down to how much an artist respects their audience and whether or not they are willing to cater to everyone or just a select demographic.

“If you make your merch insanely expensive, such that nobody can afford it, I think that you’re basically telling your fans that you don’t care enough about them to make this accessible to everyone,” Gulrajani said. “They think this should only be accessible to the people that support them financially, and I don’t think that’s fair. That’s a very transactional relationship, which I don’t like.”

On the other hand, Moore disagrees with the way smaller creators are held to a higher standard, even though they may not have as many resources to appeal to everyone.

“It kind of reminds me of when small businesses get yelled at for having their prices too high,” Moore said. “I think it’s because we demand more from smaller businesses, even though it should be the opposite because small businesses can’t cater as much to wider audiences.”

AP Macroeconomics teacher Scott Victorine has been involved with music for a long time, from listening to mainstream creators like Prince to playing in his own band with friends. Even though he agrees that the music industry often treats its artists unfairly, he emphasizes the importance of an artist’s fanbase, being the ones who allow them to continue their work.

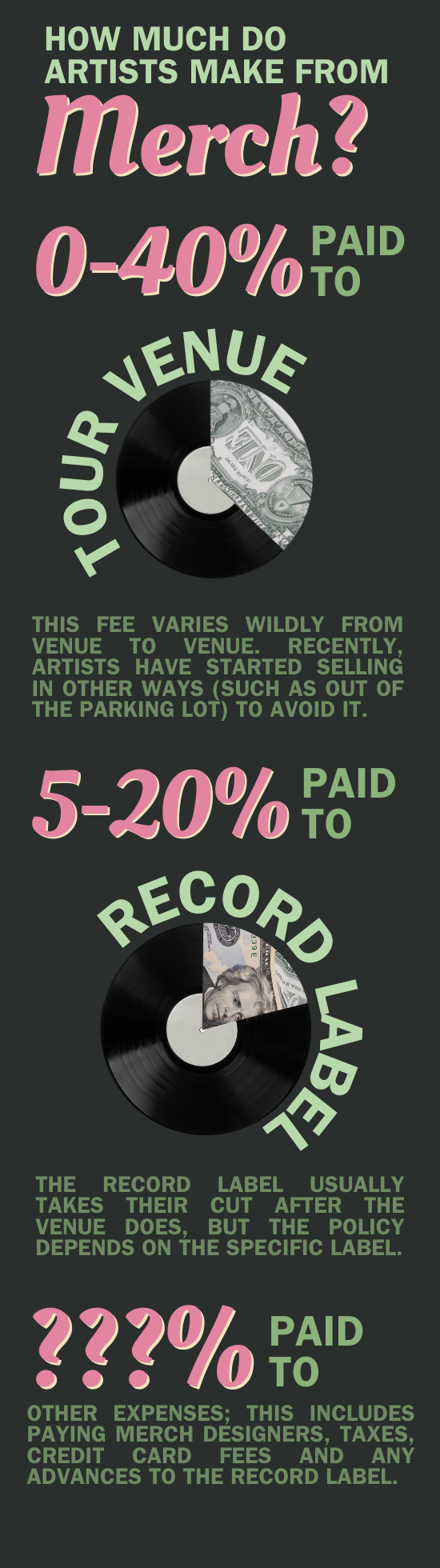

“It’s a complicated industry with record deals and record contracts, and because of this, sometimes artists don’t see much profit,” Victorine said. “There’s been a push for artists to take more control of not only their music, but their merchandise. So that might be it, but again, it all comes back to the fans. You gotta give the fans something to keep coming back for.”

Victorine sees live music often, sometimes buying shirts or CDs to support the artists. While not every purchase is necessarily worth it, he believes that the financial aspect isn’t the whole story.

“In economics, it’s called marginal analysis, where you weigh your costs and your benefits,” Victorine said. “So the benefit is different if it’s a band that I’ve listened to for a long time that I have a connection with. Would I have gone to Taylor Swift with my wife? Probably not. But there are certain bands that we actually listen to together. And for that, I would consider spending a little bit more to have that experience with somebody I care about.”

Gulrajani has had a similar experience — being a big fan of Nicki Minaj, she bought one of her inexpensive perfumes at Walmart. She didn’t end up using the scent, but still keeps the bottle. It reminds her of her bond with her sister, who first introduced Gulrajani to the rapper and influenced much of her music taste growing up.

Moore has also bought shirts and jewelry featuring bands she enjoys, such as My Chemical Romance or Cannibal Corpse. While she knows that not every cost she pays goes directly to the original artist, she still considers supporting them indirectly to be a benefit of owning the merch.

Ultimately, Victorine sees the threshold of value being different for every person and their relationship to art. While he recognizes that there are times where the prices of certain products are exploitative, he still considers buying merch as a way to give the artist something in return for the experiences they gave him.

“I think there’s a certain point where it’s worth it,” Victorine said. “There’s other points where it’s not. There’s the financial part of it, which I call the common sense part, which is like, ‘that’s ridiculous to pay that much.’ But then there’s the emotional part of it. To me, music evokes an emotional response, and in that regard, I think it’s absolutely worth it.”

(@bug_buggy_444)

(@bug_buggy_444)