New laws and housing element impact housing in Cupertino

Community members share their opinions on the housing crisis

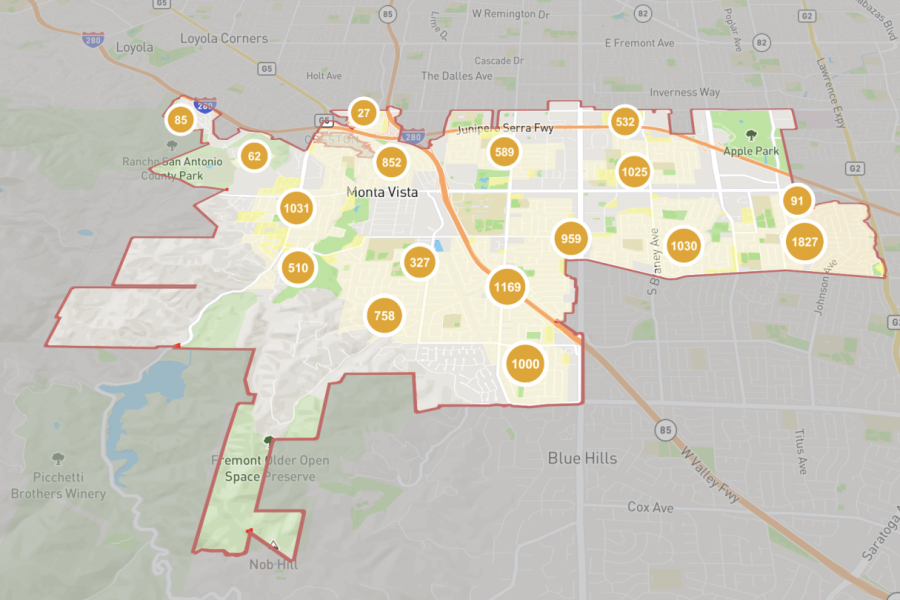

The majority of Cupertino is zoned for low to medium density housing, pictured in yellow on Cupertino’s interactive zoning map.

February 15, 2023

The cost of buying a house in Cupertino remains at around $2.4 million, seven times higher than the U.S. average, although housing prices declined throughout 2022. To mitigate the housing crisis, the city of Cupertino released its first draft of its housing element — a state-mandated document that details the next eight years of housing policies — on Nov. 18., California also passed several laws streamlining housing processes that took effect on Jan. 1.

Senior and real estate license owner Ethan Wen believes high housing prices in Cupertino are the result of parents moving to the Bay Area for the school districts.

“It’s very overrated [and] expensive, especially in Cupertino,” Wen said. “Compared to the rest of the Bay Area — for example, Los Gatos and Los Altos Hills — the houses there are nicer but they’re also cheaper, even though in Cupertino, [the] houses are really old.”

According to a study by UC Berkeley’s Othering and Belonging Institute, 91% of Cupertino is zoned for low-density, single-family homes. City Council member JR Fruen attributes the inefficiency of the zoning to multiple factors, including an increase in jobs without sufficient housing as well as community resistance to new projects.

“When lots of people show up at a public meeting to yell and scream about a new housing development that they don’t like, most city councils tend to disappear with the project,” Fruen said. “That type of community resistance is more prevalent in wealthier suburbs than it is in other places, and Cupertino is a wealthy suburb.”

Fruen also mentions dropped housing plans for Main Street and Vallco — both of which were voted against during referendum — and says another factor that has contributed to the housing crisis include Cupertino’s parking standards, which he describes as “extraordinarily high.”

However, Fruen believes a combination of new laws such as Assembly Bill 2011, which opens commercial zones to residential development, as well as the housing element could be a “game changer” for Cupertino housing within the coming years. He believes Cupertino needs a more ambitious housing element that “doesn’t just speak to the minimum state requirement,” but focuses on building a variety of types of housing.

“[The housing element will] make it legal to build housing in a lot more of the city,” Fruen said. “It would allow for not just new places in the city to have housing, but it would [also] reduce the barriers for its construction by allowing for greater densities, increasing the height limits, reducing setback requirements [and] reducing certain types of fees.”

Fruen says the model that Cupertino is built on — a “two story house with a white picket fence [and] a nuclear family in it” — is unsustainable in the long run. Senior Samuel Choi whose family is buying a home in the Bay Area agrees, pointing out how high prices drive potential residents away from Cupertino as they can find more affordable housing elsewhere.

“In the past few years, the prices in the Bay Area have skyrocketed to a point where it’s unaffordable for a lot of families, which [has] probably factored into a lot of families leaving the Bay Area,” Choi said.

Ultimately, Fruen hopes that the new City Council can take on the challenge to institute both affordability and new amenities that make Cupertino “more walkable, more bikeable [and] more interesting to be in.”

“My two primary hopes [are] that we make housing a lot more accessible to the people who really are looking to make the community better and who need it the most, and that we wind up making a better city out of it,” Fruen said.