A look at lockdowns

With gun violence on the rise, students and staff reflect on active shooter drills

February 14, 2023

An announcement comes over the intercom. The classroom falls into an eerie silence as the teacher locks the doors and lowers the blinds as students build a barrier to huddle behind. As footsteps echo down the hallway, there’s a knock and the sound of a key unlocking the door. One thing is fortunate: it’s just a drill.

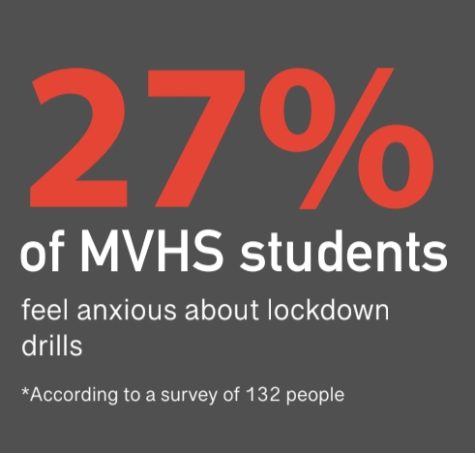

With over six mass shootings in California since the start of the year, 88% of MVHS students believe that the school should continue to have lockdown drills. Assistant Principal Sydney Fernandez agrees with this sentiment, saying that drills help people know what to do during a real threat.

“It helps to have that experience already in the back of your mind,” Fernandez said. “Your heightened emotions [wouldn’t] get in the way of keeping everybody safe.”

Senior Clay Carson agrees that lockdown drills help make MVHS safer. However, he says that the lockdowns caused by bomb threats last September were still scary for him, even with drills taking place every year.

“I felt like I was about to cry because I was really scared,” Carson said. “[In] the media, people talk about what it feels like when their school is in a school shooting, and I just thought, ‘Oh my god. It’s happening.’”

Contrary to MVHS, Palo Alto High School has not conducted lockdown drills since before the COVID-19 pandemic. PAHS junior Olivia Atkinson says that while students often see lockdowns as a “chance to miss class,” she believes that bringing drills back could be beneficial.

“I think now I feel more secure in knowing what I need to do [having] created my own safety plan,” Atkinson said. “However, I’m not so certain that other students know exactly what they need to be doing, and that has me a bit concerned that they don’t know the protocols. Having some sort of drill every year is helpful.”

For MVHS, Fernandez says the “Run, Hide, Defend” strategy is employed during active attacker situations. However, drills at MVHS focus on only the “Hide” portion of the strategy. Fernandez believes there is room for improvement but says that expanding drills to encompass other strategies is unlikely.

“It’s hard, because we’re here in school to learn and that has to be the primary focus of school, but we also have to be safe,” Fernandez said. “I wonder [if] there [is] space to do the run portion of that drill, [but] it’s not the direction that we’ve been going as a campus. We work with our sheriff partners on what to do, and their recommendation is to have these lockdown drills.”

Similarly, Atkinson questions the feasibility of self-defense drills at PAHS. She says that outside of lockdowns, other strategies should be employed that teach students other information like evacuation locations.

“I would love to see the school [come] up with different solutions,” Atkinson said. “Explain to students a simple plan of what they need to do. It’s helpful to have a clear set of rules that are already ingrained in your head that you can rely on.”

As school districts continue to make strides toward safer campuses, Carson believes that the current drills are enough but will not curb the broader issue of gun violence.

“On a societal level, I don’t think that having drills like this is the answer to gun violence,” Carson said. “Making sure that gun violence is reduced and prevented is the better solution, but I think if there’s nothing we can do to stop the gun violence from happening, what we have now is decent enough in training staff and students [for] how they [would] react in a real situation.”