“The golden son”

How gender biases in Asian culture affect MVHS community members

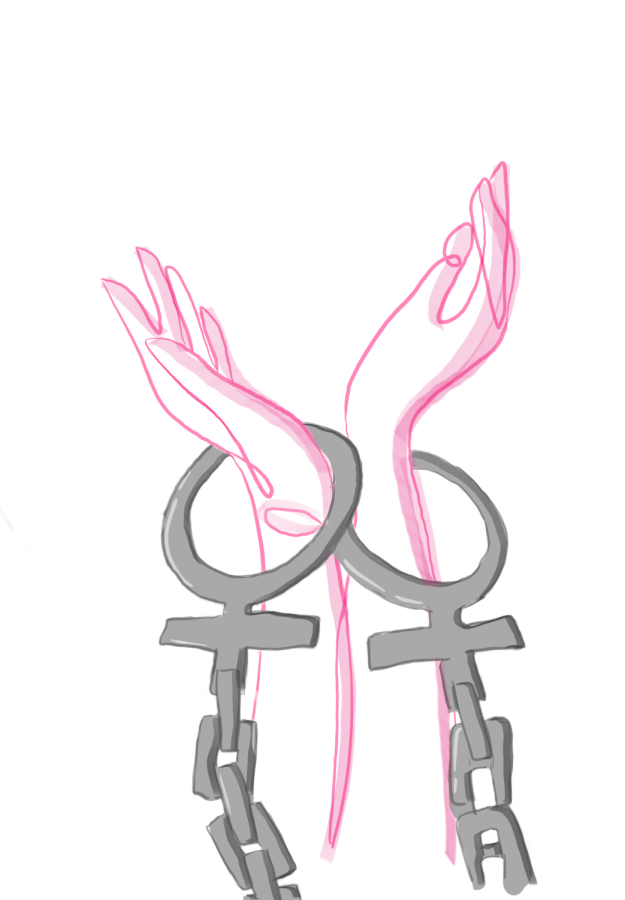

Unlearning preconceived beliefs about gender biases is the first step towards dismantling these stereotypes.

December 23, 2022

MVHS Parent Yue Chen vividly recalls standing in her grandparents’ house with her arms outstretched, watching her grandmother give her brother and male cousin money to buy dumplings from down the street. Yet, when it was her turn, Chen’s grandmother refused to give her money to buy snacks. Years later, Chen still remembers feeling outraged as she looked down into her own empty hands.

“I was really offended and I confronted her right away,” Chen said. “But not as many girls [would do] what I did. They usually accepted the situation [because] it was pretty common.”

Chen notes that this was just one of many instances where her grandparents favored her male counterparts. While gender biases vary in degree, ranging from subtly whispered sexist remarks to openly enforced gender stereotypes, they all share a continued prevalence in today’s schools, workplaces and homes. In fact, a survey of MVHS students found that 81% of MVHS students have seen instances of gender bias from Asian parents.

Indeed, Chen says gender biases are especially common within Asian families that follow traditional cultural gender norms. Many of these families often have a preference for sons, which junior Miriam Law attributes to the belief that “women are supposed to care for their children and provide food and shelter” while “men are supposed to go to work” and provide for the family.

Chen explains that these beliefs stem from traditional gendered attitudes about the roles of men versus women.

“In Chinese culture, once you’re married, you’re basically not independent,” Chen said. “You don’t make money. You’re not the breadwinner. And so [husbands] don’t treat their wife like an independent person.”

Law adds that these customs are still prevalent in some Asian families because many parents “grew up in a more traditional environment” where double standards between genders were enforced. She says that this, in turn, leads the parents to adopt the same philosophies in their own households, creating a vicious cycle of gender inequality.

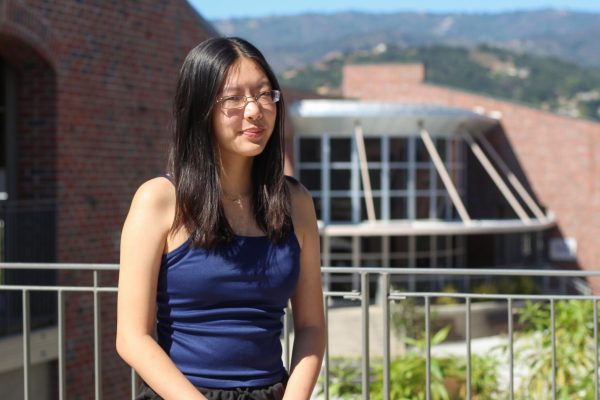

“Growing up, there were definitely higher expectations for me to be more put together,” Law said. “There were a set of expectations, [like] my parents would even criticize having a messy room saying that because I’m a girl, I should be having a cleaner room, or I shouldn’t be using vulgar language, or I should be talking or behaving a different way in which they wouldn’t enforce onto my brother.”

In a similar vein, sophomore Aster Nguyen remembers his mom scolding him for not “sitting the proper way” or for other behaviors that didn’t match what was traditionally expected of his gender.

He also recalls how he and his siblings nicknamed one of their brothers “the golden son” because their mom would always “let everything he did slide.” However, Nguyen feels that these types of gender biases and stereotypes have no substantial basis in reason.

“It’s really outdated and kind of stupid, just logically, that women and men should act certain ways,” Nguyen said. “It just makes no sense because [we] are all different people. No one’s gonna act completely the same. We’re all just humans. No one should be restricted to [acting] one way or another.”

Chen agrees that gender stereotypes should be dismantled, but she says the difficulty in challenging these views is that gender stereotypes are entrenched in tradition. Although her own experience of obtaining a higher education allowed her to become more independent and break away from these gender norms, Chen acknowledges that other women may not have the same opportunities.

“Even now, if you go to China, the young women [living] in the countryside have probably accepted the reality that their family will give the majority of the money to the [men] for education or business,” Chen said. “This makes the [women] kind of lose the realization that they can still control their future, their life and their happiness. They lose the passion to learn or to work for a better life for themselves.”

Law adds that instilling these beliefs into a young child can have detrimental effects and change how a child interacts with others. For example, she cites that girls subjected to gender bias from a young age may have less confidence to speak for what they believe in or begin to believe that they have less of a role in society.

“There are times where I tell myself I shouldn’t be speaking out because I’m a girl and I don’t have as big of a voice as a boy would,” Law said. “But I think [I’m] slowly teaching myself that I do deserve a voice in a society where I don’t have to feel held back by these gender roles.”

Despite female subordination having been a part of many Asian cultures for so long, Nguyen feels that the younger generation is more likely to change their mindsets and less likely to continue enforcing these gender norms. He attributes this open-mindedness to a change in culture and the rapid growth of internet usage.

“Younger people have the internet now where we can see perspectives from literally anyone,” Nguyen said. “And [this] allows the younger generation to be more open-minded and learn more about the way other people live their lives. This [lets] them learn how to accept other people and not hold on to the same beliefs their parents had.”

Law echoes that she holds beliefs that are different from those of her parents’, and adds that she and her parents are still undergoing a process of unlearning preconceived notions about gender stereotypes and relearning new perspectives.

“It does create a barrier [when] I communicate with my parents,” Law said. “There’s different levels of trust that we’re still trying to figure out as well. I am trying to open up to them to communicate about this more, [but] there’s only so much I can do. Especially if it’s something that they’ve grown up with, it’s hard to tell them to change what they think or what they’ve grown accustomed to.”

By communicating her thoughts to her parents, Law is hopeful that her parents will slowly reciprocate her actions and listen to perspectives different from the traditional views dominant in their culture. Similarly, Nguyen feels that parents may become more willing to broaden their views when exposed to a shift in culture.

“Over time, living in the Bay Area where there are more different and modern ideals might affect the parents to accept [these ideals] as well,” Nguyen said. “But I’d say it usually depends on how strongly the parents hold on to their past ideals and if they are willing to change.”

Law agrees with this sentiment, emphasizing the importance of parents looking past the beliefs they’ve grown up with to better understand their children.

“This goes beyond just the double standards and gender roles,” Law said. “Being a good parent is being able to empathize [with] your children and being able to see it from their perspective. And I think my parents are still trying to learn how to do that.”