Don’t ask questions

How the American school system discourages curiosity

November 15, 2022

Other than the voice of a lecturing teacher and the echoing sound of rapid typing as students hurry to copy down the information being thrown at them, the classroom is silent. Although all eyes are trained on the lines of writing on the board, most students have their thoughts focused elsewhere. Their minds race with thoughts about their genuine interests — perhaps art or writing — but students must leave those behind as they put all their energy into the overwhelming workload from the monotonous subjects at school.

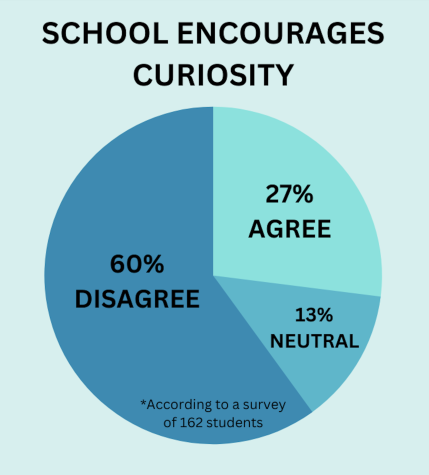

The American school system does not encourage curiosity — the skew away from trying new things is embedded in the very fabric of our grades. Limited by rubrics and word counts, we’re unable to explore because we’re so worried that departing from what is prescribed to us as familiar will somehow lower our grade. Assignments, rather than being a way to channel creativity and show that we can think outside the box, become a checklist of teachers’ expectations.

At MVHS, students tend to stick to what they are good at. If something we’re interested in doesn’t fit the subjects we force ourselves into, we push those interests aside, telling ourselves that there will be time to explore it later. We push ourselves to be book-smart instead of street-smart, because who cares if we lack a little wisdom and worldliness? At least we can rattle off the names of every U.S. president!

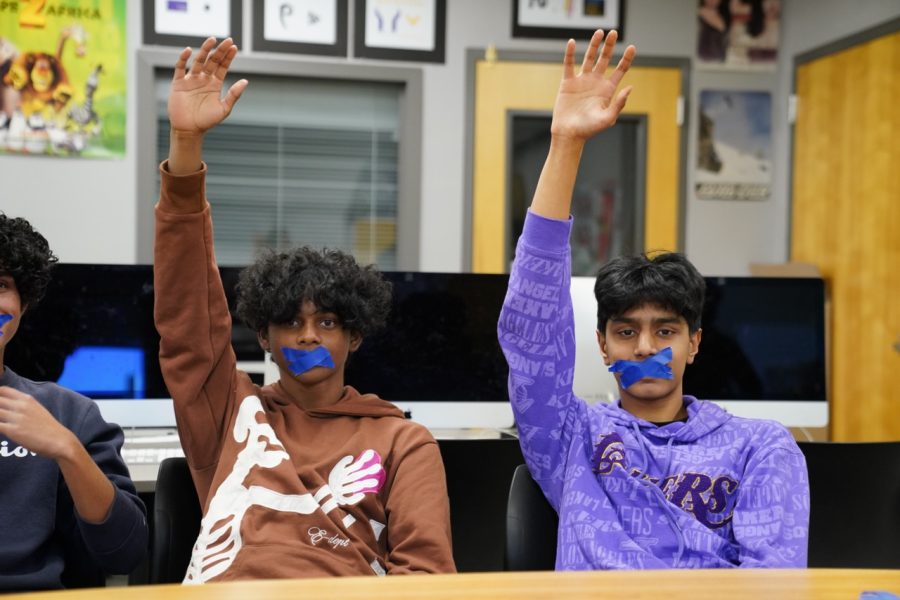

The negative aspects of this culture are visible in many MVHS classrooms. A fear of answering questions incorrectly means we no longer participate in class, unless it’s required. According to The Telegraph, as high schoolers, our curiosity peaks at four questions a day, compared to the 200-300 questions a child asks a day — curiously, the number of questions asked sharply declines when children begin to attend school. We still asked questions in elementary school, but they were increasingly met with rolled eyes and frustrated sighs from our teachers trying to finish their lesson plans. It almost seems as though we have stopped asking questions altogether: in classes where we are not graded on participation, nobody asks anything. Gone are the days when our teachers had to beg us to be silent — now, they beg us to talk.

A study by the University of Michigan showed that curious children tend to have stronger academic performance, but when schools emphasize the importance of having students stay focused on whatever task they are given rather than asking questions about broader topics, academic achievement is hindered, and it also widens the achievement gap between students of different social classes. According to an article by the Guardian, children from lower economic situations had the strongest connection between curiosity and academic performance — when we ask students to suppress their curiosity, we further disadvantage those in poorer situations by discouraging the learning style that they prefer.

School doesn’t have to be this way. Nordic countries such as Denmark, Norway and Finland rank highly for having the happiest children in the world, according to a 2021 report by UNICEF. With their children spending so much time in school, the way those countries’ schools are organized greatly contributes to this happiness. In contrast to the American school system, where kids typically enter school at age five for kindergarten, if not earlier, students in Finland start when they’re seven in a play-based model of learning. The school prioritizes the mental health of students at every step. They encourage cooperation between students and their peers rather than competition, start the school day at 9 a.m. at the earliest, avoid unnecessary busy work and assign little to no homework.

By creating a school system with room for freedom, happier students gain the opportunity to be curious and explore their passions rather than having those interests given to them. This structure encourages students to build creativity and develop imaginative minds by allowing them to truly engage with the learning process. No school system is perfect, but we can and should draw from the positive aspects of others’, especially when the data shows clear benefits.

It isn’t feasible to completely restructure the school system immediately, but in the meantime, it’s important that we learn to find snippets of time within our busy workloads to explore what we’re truly curious about, whether we think it will “benefit” us or not. Although worrying over our grades might have a hold on us, there’s one thing that school cannot take away: our autonomy. We can relearn curiosity — let’s start by asking questions again.