30 minutes or less

Teachers discuss possible agreements on reduction of homework time

May 27, 2022

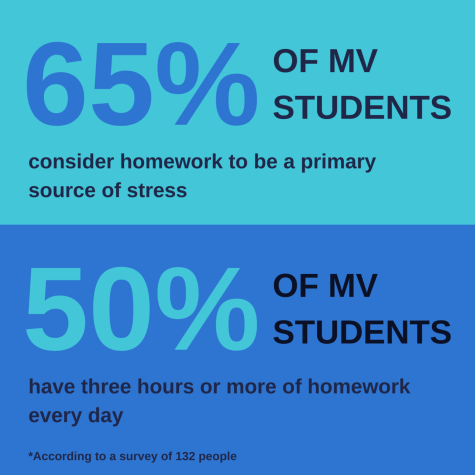

On Tuesday, April 26, journalism teacher Julia Satterthwaite led a faculty meeting during collaboration to discuss the homework related stress at MVHS. The presentation reviewed perspectives from students, parents and guidance counselor Clay Stiver and referenced a study by Challenge Success conducted in August 2020 which found that students’ academic performance was best when they had a maximum of two hours of homework each night. Then, staff interest was gauged on the idea of possibly making a collective commitment to reducing students’ daily homework workloads.

At the end of the meeting, teachers were asked to participate in a “fist of five,” an activity where they rated their agreement on the statement, “I would be interested in a collective commitment about homework load” on a scale from one to five, with one being uninterested and five being the most interested. Typically, those who held up zeros, ones and twos would be given an opportunity to share their concerns. However, because there wasn’t enough time for that follow-up, Satterthwaite says this discussion will happen at a later date after the Leadership Team has time to reflect on the exit ticket data. Senior Shivani Verma, who spoke at the meeting, recalls seeing “a lot of fives and a few ones.”

At the meeting, Verma spoke about her experiences with homework-related stress at MVHS. Verma stated that as a member of the MV Dance Team, she has struggled in the past to balance her workload with other commitments. She notes that although MVHS has attempted to relieve student stress through means such as bringing animals on campus and implementing Tranquil Tuesdays — teacher-led sessions of relaxing activities — in previous years, these solutions have failed to “address the issue, which is that we’re stressed because we have a lot of homework.” The root of the issue, she believes, is a lack of standardization between classes and an abundance of unnecessary work.

“[Excess homework] definitely affects the amount of rest I get,” Verma said. “Sometimes, by the time I’m done doing the things I literally have to do, like eat, to survive, I don’t want to do anything else because I’m tired from the entire day. And the reason I’m tired from the entire day is because I’m already sleep deprived. I didn’t sleep the night before because I was doing homework. So it just carries on every single day.”

“[Excess homework] definitely affects the amount of rest I get,” Verma said. “Sometimes, by the time I’m done doing the things I literally have to do, like eat, to survive, I don’t want to do anything else because I’m tired from the entire day. And the reason I’m tired from the entire day is because I’m already sleep deprived. I didn’t sleep the night before because I was doing homework. So it just carries on every single day.”

Biology teacher Lora Lerner believes collectively reducing homework load would not allow teachers necessary flexibility in assigning work and would hinder teachers’ abilities to cover content, especially in AP classes, where there is a preset amount to cover. She adds that quantifying learning into a minutes per day standard is difficult because students are fundamentally different.

“You give the amount of homework you think the average student, whoever that is, would need to be able to learn [a concept],” Lerner said. “But of course, for some students, they don’t need to do that much. And then for other students, that’s either not enough or takes them a really long time because they may be struggling more with the basics.”

However, Lerner agrees that a possible solution to homework-related student stress would be to make homework smarter and more efficient. She believes that the work she assigns can be divided into three categories: input, in which students are first exposed to material at home before class, in-class practice and review.

Spanish teacher Joyce Fortune has a similar approach to Lerner in assigning homework: she uses homework to allow students to preview material before class, practice and then review before assessments. One suggested solution at the meeting was to limit the amount of homework to under 30 minutes per class on block days and under 15 minutes per class for days with all seven classes. Fortune believes that strict restrictions could end up impeding students’ learning and that cutting down homework as a whole is “not the answer,” especially in a language class, where repetition and memorization are necessary for long-term learning.

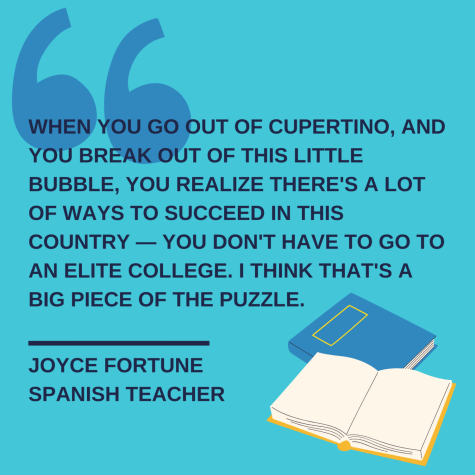

Lerner and Fortune agree that frustration surrounding homework is indicative of a bigger problem surrounding work culture at MVHS. Lerner is unsure if reducing homework would resolve the problem — less homework in one class could mean more space to take on an extra AP class. Fortune believes the focus should be on eliminating the pressure of getting into an elite college, rather than cutting homework.

“[Our students] are super dedicated, super careful, thoughtful, organized, all these wonderful things,” Fortune said. “But they’re also extremely stressed. And when you go out of Cupertino, and you break out of this little bubble, you realize there’s a lot of ways to succeed in this country — you don’t have to go to an elite college. I think that’s a big piece of the puzzle right there. It’s that sense of being stuck, of there being no other option.”

Satterthwaite points out that the academic standards for many students at MVHS have become disconnected from that for American students in general. She cites the results of a recent Western Association of Schools and College report surrounding academics at MVHS, which found that students were held to a much higher standard academically, even in college prep classes, than students at other schools.

“Because I’ve worked in another district at a school that was very different from this one, I’ve seen different types of high schoolers, and not all teachers have that experience of having worked at a more ‘normal’ high school,” Satterthwaite said. “Then they come to Monta Vista and get conditioned to have extremely high expectations that [may be] above and beyond what actually needs to happen.”

Overall, Lerner believes that although most teachers showed that they were willing to consider a collective commitment, actually establishing a concrete time limit on homework could be difficult, as most teachers “don’t want to be micromanaged to that level.”

“It’s a little bit of a tough sell,” Lerner said. “I think most teachers, if you talk to them, don’t want your lives to be stressful and horrible, right? There’s a sense of compassion for the issue, but the actual implementation of that is very hard.”