Diving into stan culture

Investigating student perspectives on the K-Pop fan community

April 27, 2022

In November of 2000, Eminem released a song about an unhinged fan who, after writing several letters to his favorite rapper and receiving no response, drives his car off a cliff. The title of the track, “Stan,” has evolved to become an official definition in the Oxford Dictionary, meaning “an overzealous or obsessive fan.”

Despite the origins of the term, many online communities of fans self-identifying as “stans” have formed around music, TV shows, books and video games. Since then, K-Pop has become one of the most prominent of these groups and maintains a vibrant presence at MVHS, through the enthusiasm of the genre’s fans and the establishment of clubs like the Korean Club and its Dance Crew.

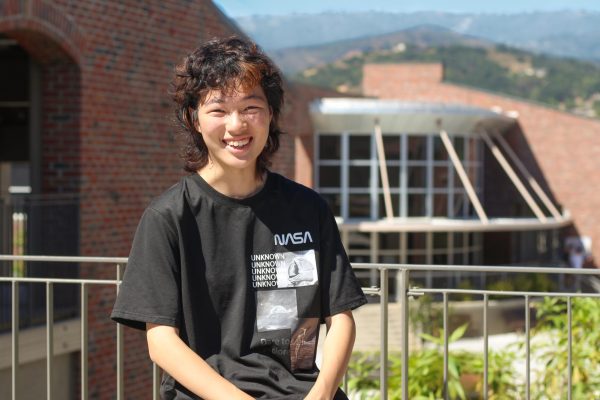

Sophomore Lemon Liu, who has been a K-Pop fan for three years, explains that many K-Pop stans are closely invested in their favorite artists’ lives, following them on different platforms or buying their merchandise and albums. However, they note that the culture is “associated with more obsession than just being a fan.”

“Some of them use it as a coping mechanism or a way to fill some gaps in their lives, which are all fine,” Liu said. “But then if it gets to a point where you’re stalking them, that would be a problem.”

Similarly, senior Edgar Tsai often sees content regarding K-Pop idols on his social media that can venture into creepiness — for instance, fan accounts impersonating official artists and groups. He believes “stanning” can be unhealthy and excessive as opposed to simply liking the genre.

“The only reason why I’m into K-Pop is because when school therapy didn’t really help, K-pop could have cleared my mind,” Tsai said. “It’s kind of like happy music.”

Stan culture has been accused of encouraging toxicity and harassment, including extreme hate and death threats towards others both within and outside the community. Junior Shirin Haldar, a fan who creates dancing and rapping content related to K-Pop, recounts being hesitant to post on platforms such as Instagram after seeing such drama.

Liu adds that this behavior also reflects negatively on outsiders’ perceptions of artists within the community. However, they believe that the toxic fans are a vocal minority, many of whom are new to the fanbase and generally “grow out of it.”

“I think those people who are quite loud on Twitter tend to leave a bad impression of the fandom to people that aren’t into it,” Liu said. “So not only does it leave a questionable image for the fans, it makes other people feel like all of us are like that.”

Stan culture is often denounced as unhealthy for the stans as well, as most stan-celebrity relationships are heavily one-sided. Although some stans may develop a friendly attachment to their favorite artists, others’ obsessive behavior can reach levels of illegality like stalking and doxxing, the act of publishing personal information such as addresses or phone numbers.

Tsai affirms that unhealthy stan behavior causes problems within the industry, referencing a recent situation in which a K-Pop group was disbanded due to its contract running out, prompting fans to show up at the group’s office to protest.

“[Some stans] do crazy stuff, like it’s not healthy,” Tsai said. “[Casual fans] just follow the music and it makes them happy. That’s kind of enough. You don’t have to do everything in your power to get [an idol’s] attention.”

Haldar thinks that “stan” can be used in popular culture as a broader term for any person who is more than a casual fan and wants to express their genuine enjoyment of an interest. To that end, she believes that being a stan isn’t inherently bad.

“I think just be careful when you are a fan,” Haldar said. “Try not to get into toxic environments and just try to make sure K-Pop doesn’t take over your life.”

Liu encourages stans to set healthy boundaries with online personas to prevent their interests from becoming draining. They stress the importance of having “another personality other than liking K-Pop” and respecting the privacy of K-Pop idols.

“I don’t want this to consume most of my life because I have other things to do,” Liu said. “But then it’s a great source of comfort and a coping mechanism as well. And I think that’s a healthy way to look at it.”