Book bans are on the rise

Tennessee ‘Maus’ controversy confronts ethics of restricting age-inappropriate content for students

Since the beginning of 2021, 156 books have been challenged across the United States.

April 6, 2022

In early January of this year, the McMinn County School Board in Tennessee unanimously voted for the removal of “Maus,” a graphic novel by Art Spiegelman focusing on Jewish experiences during the Holocaust, from its eighth-grade English language arts curriculum.

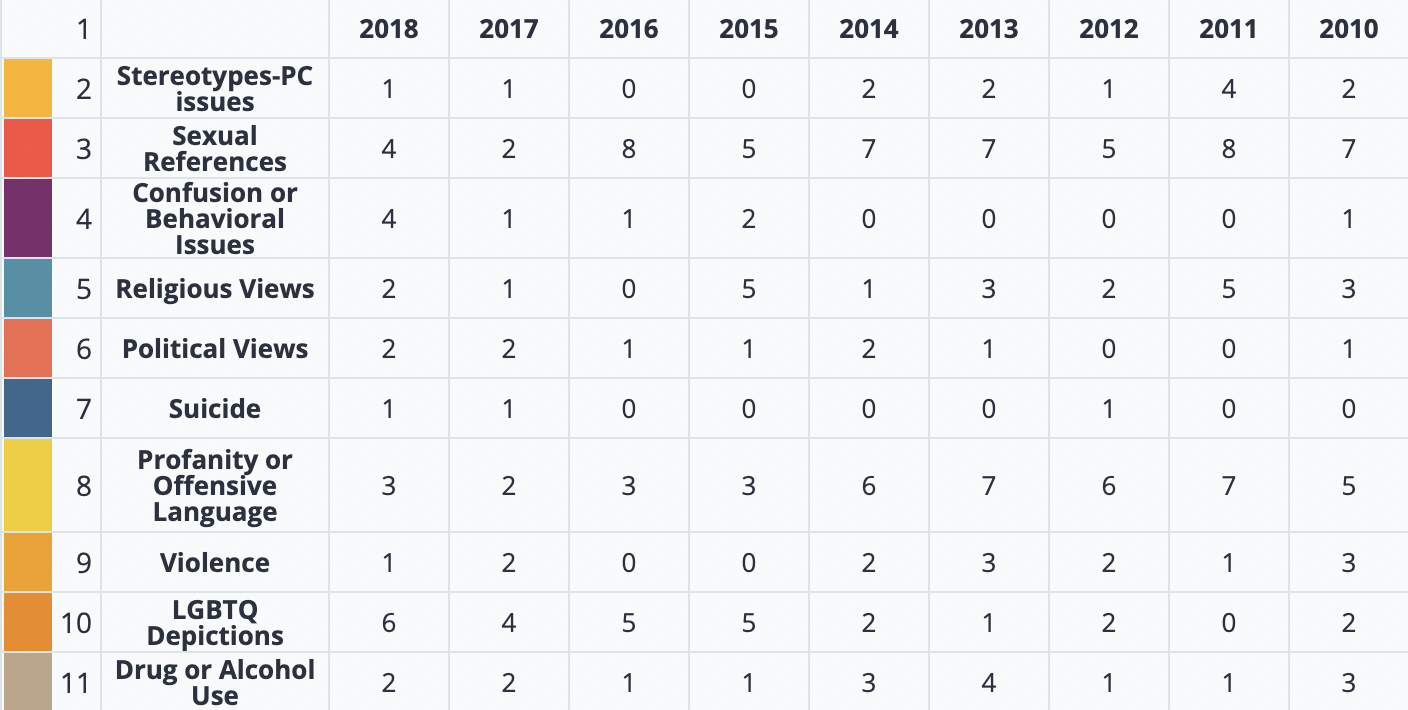

The board’s statement referenced the novel’s “unnecessary use of profanity and nudity and its depiction of violence and suicide” as disturbing and not age-appropriate for students in eighth grade. The text includes eight swear words, including the phrase “god damn,” as well as drawings of naked mice and a depiction of Spiegelman’s mother lying in a bathtub after committing suicide.

Literature teacher Jireh Tanabe believes the backlash against “Maus” is “a tragedy.” She says that exposure to historical content is vital for children to understand how the past shapes current events.

“To ban means that there’s something important in that book that people don’t want others to hear or know about,” Tanabe said. “And that’s important, because the Holocaust is definitely something that we need to remember so that we don’t repeat it.”

Library Media Specialist Doreen Bonde adds that exposure to dark topics is an inevitable reality of our world. She believes literature can be used to understand the challenges of living in a society “where bad things happen and people do bad things.”

“Banning books because they make adults uncomfortable means kids don’t get exposed to other people’s ideas and experiences and [this] limits their opportunities to learn and grow,” Bonde said.

Sophomore Sylvia Ker feels that the “Maus” ban is an attempt to “conceal the devastating history of the Holocaust from younger students.” She agrees that when a book is marked as controversial, it typically contains views that could offer readers a different perspective about the world.

“When kids are not repeatedly fed the same ideas, they are given the freedom to think differently,” Ker said.

Similarly, Bonde expresses that she is more concerned about “the greater pattern we’re currently seeing in the U.S. of censorship attempts in schools.” She believes all books present some extent of controversy and that curriculum shouldn’t restrict students to traditional ideas by banning books, especially contended ones.

Following the “Maus” ban, attempts by parents to challenge novels deemed inappropriate for children have begun to surge. PEN America tracked the legislative efforts to bar these topics, which were dubbed as “educational gag orders,” from educational institutes for over a year. Since the start of 2021, 156 of these bills have been prefiled across the U.S. with a staggering 103 introduced in January and February 2022 alone. Books discussing themes such as Critical Race Theory, history, sexuality and gender identity were frequently targeted, according to PEN America’s February report.

These efforts have also shed light on the effectiveness of book bans in preventing the spread of challenged content. In the weeks following the McMinn County ban, “Maus” soared to the top of the Amazon bestseller list and many bookstores offered free copies of the book to families in the affected district. Nevertheless, Tanabe believes that removing a book from a curriculum effectively restricts that information from reaching some students.

“I think for those who are curious and those who wonder as to why books are banned, why ideas are banned, then it should serve as a stepping point for them or stepping off point for them to find out more and actually read the book,” Tanabe said.

In the 2021-2022 school year, Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” was pulled from MVHS’s ninth grade curriculum, which is not the same as banning a book, in part becuase of the white savior complex in which a white man helps a Black man who is falsely accused of rape, but also because the PLC felt it would be good to read a text by an author of color. “To Kill a Mockingbird” is also frequently challenged for its use of explicit language, including 48 instances of racial slurs directed at Black characters. It was replaced with “Born a Crime” by Trevor Noah, a Black man who grew up under the lasting impact of apartheid in South Africa.

Tanabe plans to teach excerpts from “Maus” to students in future units.

“I think you should read all the banned books that you can,” she said. “And I would love to teach as many banned books as I could.”