En garde

Examining two different fencers’ experience with the sport

Junior Arya Srivastava thrusts her sword during a match (Photo courtesy of Arya Srivastava | Used with permission)

February 13, 2022

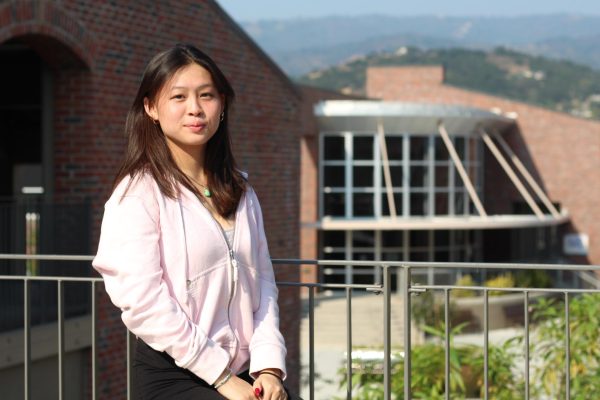

Junior Arti Gnanasekar nervously boarded a plane that would take her over 400 miles away to the BladeRunner fencing tournament at UC San Diego. Gnanasekar’s first time traveling on a plane by herself, during ninth grade, was a jarring experience, yet she remained eager for the competition. Little did she know that the tournament would become one of the most memorable moments of her fencing career, filled with excitement and new opportunities that would allow her to meet fencers outside of her small, local bubble.

Gnanasekar began fencing in sixth grade after watching the 2016 Summer Olympics. Though there are three different forms of fencing, Gnanasekar solely focuses on épée, the form that allows fencers to target all areas of their opponents’ body except for their back. Not only has practicing épée built strong hand-eye coordination skills for Gnanasekar, fencing has also helped her navigate the real world.

“I finished eighth grade in private school and then I came to Monta Vista which is public,” Gnanasekar said. “The advice my coaches gave me helped the transition [flow] smoothly, [mainly because] the obstacles I faced while transitioning from private to public paralleled moving from different levels in fencing.”

Gnanasekar says that épée’s popularity among young fencers is mainly because épée is “the style that most people go into first because it’s the slowest.” Similar to Gnanasekar, Junior Arya Srivastava, who also practices épée, believes that fencing has a lot of positive benefits beyond just exercise.

“[Fencing] definitely keeps me busy and gives me something to do,” Srivastava said. “A lot of the time I get really lazy. Sometimes, I just don’t want to do anything, but [fencing] helps add a good two hours to my day and it makes me feel productive.”

However, contrary to Gnanasekar’s initial positive experience, Srivastava admits that her first fencing club wasn’t a great fit for her. Looking back, she wishes that she “started [fencing] with a more positive mindset” in order to feel more confident about herself.

“I wasn’t really happy with fencing when I first started and I guess it was just the competitive mindset that I was in,” Srivastava said. “I was [also] really hard on myself, so that took a toll on my mental health and that’s why I took a break [from fencing] for a pretty long time.”

After Srivastava’s break, she resumed fencing at a new club, Maximum Fencing Club, and felt like she became a “more holistic person who [was able to accomplish] a lot of things.” She attributes this strong comeback to the change in environments. Currently, at Maximum Fencing Club, she feels more comfortable and confident while participating in the sport. She believes that her growth in character has helped her mature and break free from her fixed mindset that prevented her from accepting failure. Srivastava’s childhood friend, Jocelyn Tan, agrees that fencing can influence one’s mindset.

“When you win a competition or [when] you can feel yourself getting better at fencing you can feel very empowered,” Tan said. “But then when you’re not making much progress, it gets pretty frustrating.”

Tan began fencing with Srivastava at the same club, but later took a break before rejoining fencing at Srivastava’s current club, Maximum Fencing Club. According to Tan, their friendship has improved because they faced similar challenges throughout their fencing careers. Gnanasekar also agrees that fencing has allowed her to create friendships, mainly because the sport closely relies on teamwork. While working with experienced fencers at the academy, Gnanasekar has learned important lessons from them.

“[Older academy fencers] were heading into college as D-1 athletes,” Gnanasekar said. “I thought [it] was really cool that you could go into college with a sport because being brought up in Cupertino, everything is always STEM and academics.”

Her widened perspective on life has also taught Gnanasekar about the importance of fencing and the scarcity of the sport.

“I feel like the fencing community is super small,” Gnanasekar said. “I think a lot of people love the experience of fencing because it’s not as different as soccer or tennis. [If] you go into competitive levels of other sports, you’re spending the same amount of time, energy and money as you are in fencing. [Fencing] could branch out if more people were exposed to it.”

Throughout middle school, fencing followed Gnanasekar throughout the ups and downs of life, which allowed her to “build bonds with [her] teammates and coach.” This helped her learn the important lesson that “there’s always next time to revisit the subject,” which she not only applied after lost bouts but also throughout her day-to-day life.

“I don’t regret [fencing] because I learned so much from it,” Gnanasekar said. “I was able to get rid of everything around my peripheral and just think about my hands, my footwork and where my next action was going to be. I’m glad I did [fencing] in my lifetime.”