All 63 2020 National Merit semifinalists at MVHS qualify to be finalists

Examining the statistics of the National Merit Scholarship Program

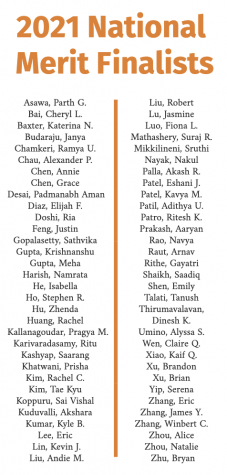

A graph depicting the number of National Merit Semifinalists at MVHS from 2015 to 2021.

April 5, 2021

On Feb. 8, the National Merit Scholarship Corporation (NMSC), which is affiliated with the College Board, mailed letters to 15,000 high school students nationwide who qualified to be National Merit Finalists. Of these finalists, 63 were MVHS students, making MVHS the school with the second highest number of finalists in California, following Lynbrook High School. This year, 100 percent of MVHS semifinalists who applied were accepted as finalists, compared to a 93.75 percent nationally. Senior Navya Rao, a finalist, says that this discrepancy is due to the strong competitive academic culture that is present at MVHS.

“I think at our school, a lot of us really get into [the] peer pressure and herd mentality,” Rao said. “We see a lot of our peers and friends applying to be a finalist and getting the finalist positions. We’re equally motivated to do the same but also pressured to do the same, which is why I feel like a lot of us feel like we have to study hard and become semifinalists or finalists.”

Although senior and finalist Saarang Kashyap agrees with Rao about the element of peer pressure, he also believes that the overarching reason that more students at MVHS are semifinalists or finalists is because their ideals are different than students at other schools.

“[Monta Vista] students are extremely hardworking and… everybody tries to put in their best effort into everything,” Kashyap said. “[Monta Vista students] have ideals of hard work and dedication to whatever they’re attempting and they always strive to be the best. I feel that sort of separates MV students from students in other schools or districts.”

Unlike Rao and Kashyap, senior Janya Budaraju believes that the primary reason that MVHS outperformed other schools is because of the socio-economic privilege that students tend to benefit from.

“[MVHS] is in a county and more specifically a district where the median income is a lot higher than the national average,” Budaraju said. “There’s a pretty high degree of privilege I think that goes into being able to excel at standardized testing: a lot of people can afford prep books, people can afford tutoring services… while that’s not always the case for people from other districts.”

In the future, approximately half of the finalists will either be selected for the Merit Scholarship to receive $2500, or will receive corporate or college-sponsored scholarships of varying amounts. In order to qualify for these scholarships, students must take the standardized test known as the Preliminary SAT/National Merit Scholarship Qualifying Test (PSAT/NMSQT) during their junior year.

For the Class of 2021, students who scored in the top one percent of their state were selected as semifinalists and notified in September 2020. Semifinalists who showed academic achievement by having a grade point average of 3.5 or higher then had the option to apply to be finalists by submitting an application requiring a personal essay, an official letter of recommendation from their school and a list of extracurricular activities. Rao chose to submit this application because of the chance of winning a scholarship and saving on college tuition, and because she did not find the application very difficult as she was able to reuse an essay from her college applications.

One percent of high school seniors nationwide were selected as finalists compared to the 11 percent of MVHS students who were chosen, despite California’s higher average state score threshold of 221 compared to the national average cutoff of 215. To calculate their index score, students add up the number of problems they answered correctly for each of the three sections and multiply by two. This means that students in California can only get about nine problems wrong and still qualify, whereas students in some states can get up to 15 wrong answers. Although Budaraju does not believe the difference in qualifying scores is completely fair to students in states with high cutoff scores, she understands the rationale behind it.

“I knew about [the cutoff score] before taking [the PSAT], but it was a little more striking when I saw that like a lot of my friends [who did not qualify] would have made the cut off in other states,” Budaraju said. “But I think that going to a high school like Monta Vista where we’re already in a more competitive environment than most other places almost prepares people for having a higher cutoff or having higher standards to [become a semifinalist].”