Drawing a curriculum: Art in the classroom

Exploring teacher and student opinions on integrating art into curriculums

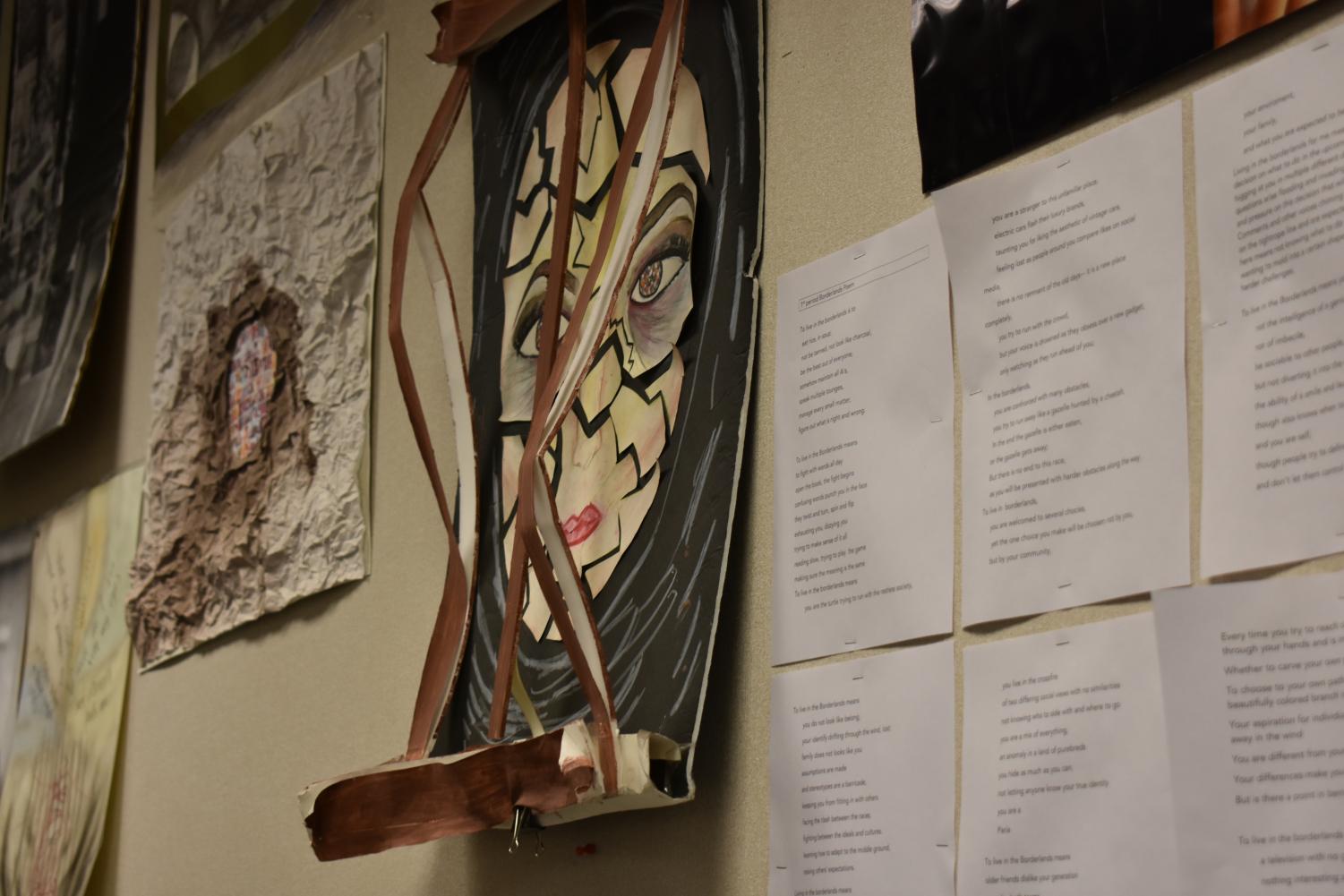

Paintings from a World Literature project line the front of literature teacher Jireh Tanabe’s classroom.

Literature teacher Jireh Tanabe’s classroom is unlike those of some other teachers. Instead of the assortment of photos, posters and motivational quotes commonly found on the walls in other classes, the walls of her room are dotted with paintings, etchings, digital designs and other colorful artworks — all produced by her students.

Tanabe has woven art projects into her literature curriculum ever since she began teaching, recognizing how beneficial expressing ideas through art was after being assigned a school literature project when she was younger.

At the beginning of her teaching career, each unit in Tanabe’s curriculum was paired with an art project. But over time, she has moved towards less frequent, synthesis-based projects that encourage students to collectively think about multiple texts rather than individual ones. Tanabe believes that the different medium challenges the way students express their understanding of the content.

“[Students are] so used to having a formulaic way of expressing themselves that I want to give them another way of expressing themselves and communicating what they understand,” Tanabe said. “So many students here are artists in ways that we would not expect because all we see them as are STEM students, or students good at ‘X,’ that we don’t allow them to express themselves in a way that’s more creative.”

While art projects might seem intimidating to some students, especially to those who don’t have an art background, Tanabe says that most students, regardless of their prior art background, usually find some success through this mode of expression.

“I think [students] think it makes [class] harder, because like me, a lot of them don’t think of themselves as artists,” Tanabe said. “I’ve never taken an art class, so I can’t go up against people who have created things on my walls. But I also see people who have had no training at all represent what they thought, and that, to me, is super powerful.”

The most striking art pieces from over the years accumulate on Tanabe’s walls.

Junior Shyam Sundaram believes that art projects implemented in class are not only important for encouraging creative expression, but also allow students to build an entrepreneurial skill set. He says that in addition to the art credits requirement at MVHS, its integration could see broader implementation across classes to benefit students.

“A lot of the work we do in school is just learning material and learning content — we never really create content,” Sundaram said. “I feel like [art is] important to [becoming] entrepreneurial and being successful — everyone who is entrepreneurial, when they do something, never follows a script. I don’t think it’s just a hobby. Being able to create new, original work can be helpful in any field.”

Sundaram says that in literature classes, for example, art assignments indirectly reward those who take risks because they end up gaining more knowledge. As a former student of Tanabe’s World Literature class, he appreciates the extent to which the seemingly intimidating open-ended art projects pushed him to take intellectual risks that ultimately proved to be rewarding.

“I like the idea of taking, [Tanabe] said, academic risks — she wouldn’t punish you if you took a risk, or [if] you didn’t go by the rubric and did something original,” Sundaram said. “No one else ever did it because they [didn’t] want to risk it. But I think that’s a good idea.”

Junior Victor Li shares the mindset that the integration of arts helps reinforce literary understanding, but he believes different learning styles among students also plays into the success of arts integration. Li says that arts integration can help visual learners in particular grasp literary ideas more easily.

“Arts integration and its utilizability is definitely contingent on visual learning and how a lot of the student population are visual learners,” Li said. “Having just one style of learning in the classroom is not fair for them. Arts integration is important for the inclusion of all students and all learning types, and in literature classes, I think [it] is important to understanding literature in different ways that some students might have a hard time understanding just through writing.”

Beyond the literature classroom, Sundaram believes arts integration builds on fundamental skills that other forms of assignments can actually take away from. He believes that applying one’s knowledge to create something original is far more valuable than just regurgitating that knowledge into an assignment.

“If you simply have content and you’re supposed to memorize it and just write down the correct answer, you’re simply a human copying machine,” Sundaram said. “You’re essentially doing the role a computer can do. There’s really nothing new — you’re not creating anything. The only reason we don’t use computers for everything is because we can create new ideas, new products.”

Sundaram believes arts should be more closely integrated into school classes. He also says that because many students, himself included, often question the value and time trade-off of engaging in art as an extracurricular, directly integrating art as a regular part of class can ensure more students have the opportunity to experience it directly.

“It’s not just for [the] experience; I think it’s absolutely necessary for every student to go through some form of creative thinking,” Sundaram said. “It’s one of those beneficial things that would help them later on.”

Integrating art, however, can be difficult in certain classes. Sundaram says that it would be impossible for every teacher at MVHS to effectively integrate art into their curriculum. He believes that some classes don’t need arts integration because they already indirectly build on the skills art usually supplements.

“[Art] also aids in problem solving — the ability to solve difficult problems, come up with new ideas or new solutions to a problem — I mean, that’s essentially math,” Sundaram said. “This single equation, you can solve in a multiple variety of ways — there doesn’t have to be one exact way to do things. Through creating original work, you’re able to think through how to visualize or how to attack different problems.”

Sudaram says that as long as art is there in a student’s schedule, it’s helpful. But certain classes like history and literature, according to Sundaram, are more suited to incorporate art because without some creative impetus in the curriculum, they would otherwise be memorization-heavy.

Art is often used to represent complex ideas in different forms.

Li adds that each classroom should be different in how they implement art because the teacher should always make the final call.

“It’s up to the teacher and what they think is best for their classroom,” Li said. “I don’t think that I should be saying what teachers should and shouldn’t do. Teachers should have choice in how they present material to their classrooms because only teachers are best acquainted with each of the needs and learning styles of their students, but I think more teachers should see this as an option for their students that are more visual learners as opposed to auditory or written learning.”

Sundaram believes that aside from the potential educational benefits of art, integrating it into the curriculum also offers a healthy and creative outlet for expression that can benefit students’ mental health in their hectic schedules, help them organize their ideas and learn more about themselves in the process.

“[Art] challenges people to learn more about their own ideas, what they’re thinking, because a lot of the times some people think things that they don’t believe,” Sundaram said. “It’s like why people will keep diaries — if no one’s ever going to see it, why do you keep it? … If you’re actively putting your own ideas onto a canvas [or] onto another platform and viewing what’s in your mind, you’re essentially having a conversation with yourself: you’re getting to know yourself better, and you’re not as much [of] a mystery to yourself.”