Retake remake

Teachers explain their motives behind offering opportunities for improvement

November 5, 2018

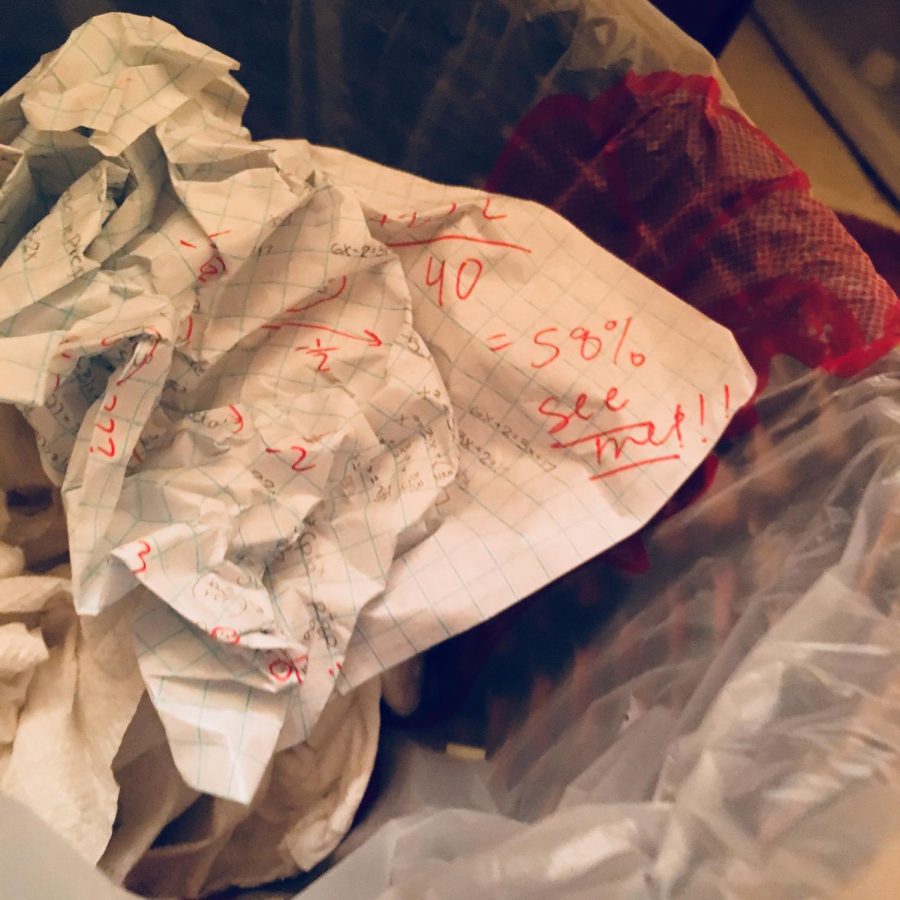

Almost every student is familiar with the sensation of receiving horrible scores for a test they studied really hard for. The gut-sinking feeling comes accompanied by a subsequent frantic search for a teacher’s syllabus, or message to a friend, to find out whether a retake will be offered. With the differences in teachers’ policies, retakes are not a guarantee, introducing a plethora of student concerns about the integrity of retake policies and whether they are truly beneficial in helping a student achieve mastery of a subject.

According to sophomore Anusha Adira, it’s the teacher’s responsibility to ensure that students are understanding concepts and doing well on exams in their classes. Regardless of what level or department, Adira believes that exams are a reflection of how well the teacher taught the content and students should be allowed to do retakes. As such, she believes that teachers should hold themselves accountable and be aware of when they’re not teaching “well enough.”

However, physics teacher Jim Birdsong has a different perspective on the matter. He believes that students should be rewarded for persistence and hard work, and exams are simply a measure to motivate students to be proactive about their learning. His policy allows students to retake exams as many times as necessary to get up to an 80 percent.

“I want to reward people who put in the work first, because what happens is kids push things off and wait until later to learn rather than being motivated to learn it as they go,” Birdsong said. “A good happy medium would just be to make sure that everyone can get a B.”

Despite having this incentive, Birdsong asserts that the final exam score is essential to confirming the accuracy of a student’s grade. He explains that the final weighs as 30 percent of a student’s overall grade in his class (10 percent less than in previous years) because it serves as a backup that allows students to demonstrate mastery even after the conclusion of a unit.

“If they can’t get an A on the final, then everything they’ve learned is [pointless],” Birdsong said. “We made it to the Super Bowl so we should automatically win? I don’t think that. The only way you can get an A is if you get an A on the final.”

Similarly, Spanish teacher Molly Guadiamos notes that students need to understand basic concepts to be able to move forward in their learning, which makes it imperative for students who missed information to go back and relearn the concepts. While she does encourage students to come in for extra help, she hesitates to offer retakes for her exams.

“I don’t do retakes per se [because they’re] pretty cumbersome and it’s pretty hard to make a different test that’s the same quality,” Guadiamos said. “My policy [of potential credit for test corrections] is really kind of directed at somebody who is in danger of their grade dropping to a D or an F.”

Both Birdsong and Guadiamos reason that students should not expect to get an A in the class without demonstrating that they are making the effort to be proactive and mindful in their studies. They concede that students have varying capabilities, but maintain that only students who are outstanding deserve an A in the class.

“To me, an A student will do everything to learn it in time and will make sure that they’re catching up before a test,” Guadiamos said. “There are ample opportunities for practice and things where students should be aware if they don’t understand a concept.”

To further address growing concern about students obsessing over their grades, Birdsong attests to the illogicality of trying to determine a grade based solely on test scores.

“People think that determining their grade is a mathematical thing and it isn’t,” Birdsong said. “[Teachers] can give whatever grade we want, it’s just easiest if we have reasons for it.”