Exams in motion

Physics teachers and students discuss the effects of AP Physics 1 assessments and their weighting

October 15, 2018

Sophomore Upasana Dilip stared into her computer screen, reading and rereading a clump of questions from a past Calculus exam. She yawned before looking down at her notes, desperately scanning the numbers for a strategy to break through the stubborn question. It was already midnight, far too late to contact her teacher, and she could only imagine how the test the next day would unfold.

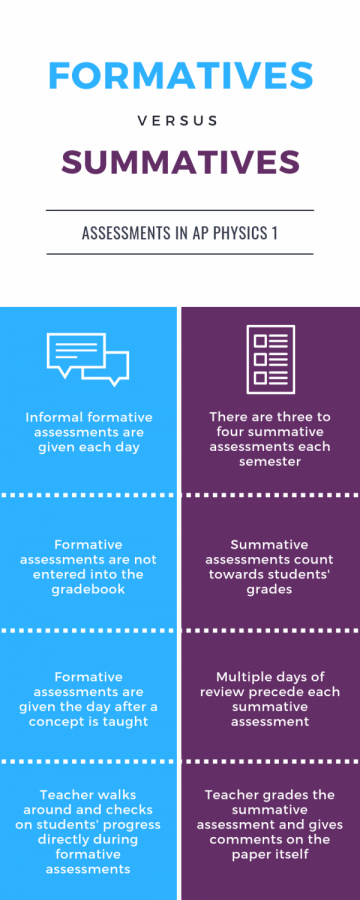

To Dilip, preparing for any test brings an immense amount of stress and she constantly worries about being underprepared, especially in classes with frequent exams. In order to combat this student stress, physics teacher Julie Choi says that the physics teachers have collaborated to create a system which involves fewer summative assessments and aims to provide students with plenty of time to review beforehand. To ensure students are learning consistently and understanding each concept, teachers have incorporated several formative assessments, which are not entered as grades.

“If it’s done right, in the ideal world, then having just three or four tests is enough,” Choi said. “The idea behind having less tests is to actually decrease students’ stress because if every single one of our formatives were graded, then you would have multiple quizzes but students would not necessarily be doing that well.”

One benefit of having fewer summative assessments is an increased amount of time to review the test material. Dilip appreciates this aspect of the physics assessment system because she enjoys the accessibility of asking her teacher for help and the time to digest what she learns.

“I like multiple days for review because you can ask your teacher questions,” Dilip said. “You have time to really understand what you don’t know. But then, in math, I don’t know something the day before the test and then I have to relearn everything.”

Choi agrees, explaining that the system would have helped her if she were a student.

“I think multiple review days help because that’s when kids can consolidate their things,” Choi said. “With physics, I think it requires a lot of input on your own time, but if you’re just kind of left to study on your own sometimes, you won’t necessarily study. I wouldn’t study, I procrastinate all the time. So I think when students are able to have a set amount of time at school to do it, it helps.”

Despite receiving more time to review, Dilip shares that she studies very little for classes with weekly tests while she spends an entire day studying before a physics test. Sophomore Andie Liu agrees and believes that having fewer summative tests often results in more pressure to do well on each test.

“For math, if you do a little worse, you’ll be like ‘there’s a test next week, it’ll be fine,’” Liu said. “You use that to boost your confidence. But if you completely flunk a physics test, then you can lose the motivation to bring it back up because there’s not a lot of opportunities to do so.”

Choi acknowledges these flaws and plans to tweak her assessments so that students have more opportunities to improve their grade.

“Next unit we are planning to do formative quizzes and that way it sort of counterbalances the summative tests,” Choi said. “I understand that for a lot students it’s a big pressure because [summatives] are worth a lot of percentage. Having few tests may feel like if they have a bad day, then they’ll just kind of get screwed over, and I understand that.”

Aside from the routine tests within a class, Liu finds that finals are often weighted heavily. In particular, she expresses concern for her physics final, which will be worth 30 percent of the overall grade.

“Since the final’s going to basically be all the tests combined with less time, that just sounds like a nightmare,” Liu said.

Choi sides with Liu, believing the weight of the final is a bit too high from a student’s perspective. She would prefer to have the final be weighted 20 percent of students’ grades. However, she would not want summative assessments to make the bulk of the grades either, so she believes reaching an optimal weighting system would require a lot of redistribution in different types of assignments or assessments.

Though Choi and other physics teachers have been constantly adjusting their style of assessments, Choi points out that there is an inevitable culture of hyperfocusing on grades at MVHS. Although she does not believe the tendency is healthy, she understands students’ perspectives and is willing to accomodate them.

“I understand that there’s this grade pressure in MVHS, so if you get a C, which is considered to be average, nobody would be happy,” Choi said. “People would feel really stressed out, so we make the average a B or an A and I understand that. I have no problems with that at all. That’s just the culture here.”

As Choi works with other teachers to continue improve their grading systems, she offers a reminder that teachers are often trying to incorporate student feedback into their classes.

“We’re working on it,” Choi said. “I think we’re listening to students’ inputs and figuring out a balance as to how we can make students who deserve an A get an A, but at the same time, not making everybody else feel like they have failed. It’s a learning process.”