Story by Andrea Schlitt and Elizabeth Han

he was told to check the box for a waiver if she applied for one. Her heart sank.

“I didn’t know until I sat down at the testing center,” said Sophia Alejandre class of 2015 graduate. “I was like, ‘You can get a waiver?'”

In a conceptual sense, college is the four years a student spends pursuing a major of their choice. The institution itself demands a considerable amount of money, but it doesnít end there. What students do during their four years of high school add up to create what could be considered the hidden costs of college.

Journey to success

Standardized tests are the foundation for college applications. Over $100 for both the SAT and ACT, another $100 for each AP test and $50 for the SAT II — the fees build up over time as students make these payments multiple times a year.

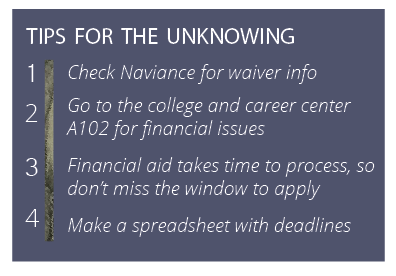

MVHS students are informed of waivers through Naviance notifications sent out from the college and career center, but the opportunity is sometimes overlooked. Even if they’re aware of such options, students must voluntarily come forth to the school to request a waiver. Career and college advisor Le-Xuan Cao claims that because the school doesn’t have access to a list of students who need waivers, they are unable to inform them beyond the Naviance messages.

“I wish I had the list [of students], but I don’t because it’s so confidential,” Cao said. “I would reach out to them individually, but I can’t.”

For the SAT, this adds an extra strain, as taking it more than once is a luxury some canít afford. Alejandre was a victim of such unknown offers — only when she sat down with her $50 scantron on the day of the test did she discover that she could have taken it not once, but twice, free of cost. Afterwards when she requested a waiver for the test, it was already too late.

Apart from the cost of the tests themselves, the level of the playing field often shifts depending on the amount of money a student puts forth in preparing for these tests. For students here, the money usually ends up in test prep courses, such as those offered by Elite Educational Institute or Excel Test Prep. Based on a survey of 60 MVHS seniors, 73 percent have taken an SAT/ACT prep class. Though not required, many parents and students look to these hands of assistance, exchanging their money for an easier way to polish their college applications.

Senior Anindit Gopalkrishnan is one of the many students who benefitted from this trend. Through an SAT course costing him almost $1000, his score took a jump of over 17 percent.

“I paid $800 to $900 on my SAT course, but I don’t think a lower income family would have had that money,” Gopalkrishnan said. “I don’t think that part is fair.”

Although students like Gopalkrishnan are aware of this privilege, many take it for granted. Alejandre recalls that the SAT classes were out of her reach due to her financial situation, leaving her with nothing but a workbook at home to study with.

She remembers shocked classmates when they found out that she took no classes, which they insisted were necessary for a better score.

According to Alejandre, many students consider these extra classes as one of many necessary steps to getting to a better college, but some people just donít have the means to afford them — even in an affluent school like MVHS.

However, it doesn’t end there. Test scores and grades can only do so much to help a student stand out in their college applications. Thus, to further strengthen their resumes, students take part in extracurricular activities, most of which demand yet another pile of money.

Senior Julia Cho has had access to these opportunities, some entailing more costs than others. She attended a several thousand dollar Johns Hopkins summer program called Center for Talented Youth for two years and also gained an internship at Berkeley, in which she had to pay for her own transportation fees. Though she admits she initially pursued both programs with the intent of benefitting her application, she claims to have garnered valuable lessons through them as well.

The application

Besides the numerous spendings under the label “college”, the application itself adds to the cost.

According to the U.S. News and World Report, the average costs for one college application can range from $37.88 to $90, excluding the cost of transcript and Secondary School Report fees. Three or five dollars to send an SSR report may sound reasonable to some. However, students are often encouraged to send multiple applications for both an increased likelihood of acceptance and the feeling of securi ty — thus the average cost of college applications in reality climbs over to the hundreds, even thousands.

ty — thus the average cost of college applications in reality climbs over to the hundreds, even thousands.

Following the SAT incident, Alejandre learned to exempt herself from these high prices through waivers schools offered. On the other hand, Cho is aware of the costs, but has decided to apply to around 25 colleges this fall.

“In terms of application fees for schools, they get so much money for tuition in the first place. I

don’t understand why they have to charge more on top of that,” Cho said. “It’s nice that they waive it, but even if you’re able to pay for it, I don’t think it’s necessarily [reasonable].”

To help with the application process, both Cho and senior Nanette Wu receive outside help like many other MVHS students. Under their parents’ recommendations, Cho goes to a college counselor and Wu attends a college essay writing class. The high costs do not hinder the families from the chance to perfect their applications at ease.

As for Alejandre, the waivers weren’t enough for a smooth application process. The struggle that she faced isn’t uncommon for those without extra hands of assistance. She had no access to the costly college counselors or other classes. Her parents couldn’t provide any advice. Hence, she had to tackle the process alone.

She attended a few programs that MVHS offered, including La Pluma’s college workshop, but she wished for further directions as she felt lost in filling out the forms and submitting them on time. Seeking additional help, she contacted one college specifically about financial aid, but she received no answers.

“The website wasnít very good. I tried to call in, but I just kept getting transferred to different departments,” Alejandre said. “I couldn’t get a clear answer from anyone, so it was extremely frustrating.”

Only after a student’s acceptance into a college do people begin wrapping their heads around the costs of college — tuition, dorms, etc. Starting with SAT’s and ending with college applications, however, the true costs emerge much prior to these four years. Some costs are more hidden than others, but the fact is that they exist. And students struggle.

“A lot of people aren’t aware about financial problems,” Alejandre said. “[It’s] not out of ignorance, just some people haven’t been able to experience them.”